Commemorating the death of George III: A reflection on the 200th anniversary of his death

By Arthur Burns and Liam Fitzgerald

Arthur Burns is professor of Modern British History at King’s College London and academic director of the Georgian Papers Programme

Liam Fitzgerald is a 2nd-year PhD candidate at King’s College London working on the British Museum’s collection of prize medals and their role in the popularisation of agricultural improvement in 18th- and 19th-century Britain.

__________

The two hundredth anniversary of the death of King George III falls on 29 January this year. To mark the occasion, the Royal Mint has issued a commemorative £5 coin [fig. 1] – in effect a collectible commemorative medal, for all its nominal face value (it is for sale in a range that embraces a cupro-nickel version at £13 and a gold proof coin costing £2,295). The obverse bears Jody Clark’s 2015 portrait of Queen Elizabeth II; the reverse a design by the Royal Mint’s graphic designer Dominique Evans, whose other work includes the £2 Jane Austen commemorative coin released in 2017.

Figure 1: The 2020 commemorative £5 coin issued by the Royal Mint © Royal Mint

In many ways this is a very appropriate way to mark the anniversary, for the king’s death itself prompted the issue of several commemorative medals. Nor was this the only occasion in George’s long reign to be marked by the striking of a medal, beginning with his accession to the throne in 1760. These medals in turn took their place among a profusion of medallic commemoration and celebration in later Georgian Britain, recording events international, national and local, and stretching from luxury productions in gold to cheaper token-like issues in base metal.

At the heart of Evans’s design is a portrait in profile of the head of George III based on that which appeared on the last coins issued in his reign, a less alarming but still striking variation on the notorious ‘Bull Head’ portrait executed in red jasper by the Italian cameo-engraver Benedetto Pistrucci (1783-1855) and engraved by the Chief Engraver at the Mint, Thomas Wyon the elder (1767-1830). The ‘bull head’ portrait adorned the silver half-crown coin issued in 1816 [fig. 2] as part of a wider recoinage (Pistrucci would also famously design the St George and the Dragon which has featured on British gold sovereigns since the first were issued in 1817). In the course of a reign in which shortages of coin and of the metal from which to produce them were at times an issue, and the need for currency especially pressing during the French Wars, George also witnessed several important changes in national coinage and his portrayal upon it.

Figure 2: The 1816 ‘Bull Head Half Crown (& 1818 variant): image www.josephinecoins.com

It therefore seems an equally appropriate way for us to mark the anniversary by reflecting on the commemorative coins relating to the king’s death in 1820, and also more broadly on the king’s life as recorded in coin and medal over sixty years.

Medallic art and culture had reached its zenith by the beginning of the nineteenth century. At this time medals were being issued at a variety of social levels, both to celebrate significant figures, and as prizes awarded by societies for innovations in farming, industry and commerce, as well as discoveries in the natural sciences. The ubiquity of the medal derived from the fact that it held a dual function. In one sense, medals were devices that conferred social distinction, converting the recipient into a physical embodiment of achievement for others to emulate. On the other hand, unlike other honorary prizes, medals also had a monetary value based on the metal from which they were made, and so could be also exchanged for financial reward. Therefore, from the Royal Society of Arts to the local improvement club, by the end of the eighteenth century medals had become a byword for achievement and prestige.

As their popularity increased, the designs of medals developed to suits the needs and interests of their patrons. Earlier images, which relied heavily on the classical traditions of medallic art, were replaced by motifs and iconographies that reflected the specific achievements for which the medals were to be awarded. Moreover, the increase in demand for medals led to structural changes to the locations and methods of production. The establishment of the Soho Mint by Matthew Boulton in 1788 challenged the primacy of the Royal Mint as the dominant producer of medals, and saw a new wave of engravers, such as Conrad Heinrich Küchler, come to dominate the market. Boulton’s invention of the steam-powered press also enabled medals to be mass-produced in cheap, base metals. These prizes were awarded in vast quantities at local fairs and agricultural shows, and their designs came to reflect more acutely on the regional societies and communities of their issue.

Figure 3: The ‘Arts Protected’ medal by Thomas Pingo, 1760: RCIN 440048, Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020

And yet, despite this diversification of medallic design, one of the enduring tropes of medals from the period was the image of the monarch himself. Throughout the course of his reign, a host of medals were produced that bear the king’s portrait. These medals not only demonstrate his position as patron of the new institutions, but also his personal interests and involvement in spurring improvement. The Arts Protected medal, produced in 1760 by Thomas Pingo (1714-1776), chief engraver of the Royal Mint [Fig. 3], reflects on George’s avid appreciation and role as supporter of the arts, an admiration he would continue to affirm upon founding the Royal Academy in 1768. Equally, Küchler’s Board of Agriculture medal [fig. 4], produced for the institution in 1797, highlights one of George III’s great passions: farming. This particular award became highly prized by great estate owners throughout Britain, an award that symbolised their patriotic duty as ‘patrons of the nation’.

Figure 4: The Board of Agriculture medal, by Conrad Heinrich Küchler, Soho Mint 1797 (Image: Numisbids.com)

It is perhaps worth remembering also that throughout the course of his life, George III was an avid collector of medals. His ‘Grand Medal Case’ held an array of ancient and contemporary coins and medals and formed the bulk of the British Museum’s collection when it was bequeathed by his son George IV in 1825. Therefore, for a collector and recipient of multiple medals, what better way to commemorate the life of the King than an issue of his own?

In one sense, the death of George III presented a particular challenge to those wishing to mark the passing of the monarch. For almost a decade, the king had in effect been a cypher. Following the death of his daughter Amelia, the king had experienced a return of the mental illness he had already suffered for several short periods earlier in his reign: but this time there would be no recovery. In addition his sight had failed, and his hearing too would be affected; by his last years senile dementia may have added to the mental disorders which some believe were a result of porphyria and others a form of mania. The future George IV was declared regent on 5 February 1811; thereafter the king, no longer an actor in affairs of state, isolated from his queen and children, and secluded at Windsor under the watchful but increasingly routine supervision of a series of physicians and attendants, was known to his nation only through occasional sightings on the terrace at Windsor or reports to parliament or the Queen’s council. Few images of this period of the king’s reign survive, and those that do offered no basis for portraiture in a celebratory mode. How then iconographically to mark the royal demise?

On the reverse of the current coin, Evans has chosen to highlight three aspects of George’s life far removed from his political and national responsibilities, marked only in the formal framing structure of the design with the floral markers of the four home nations and the inclusion of his royal cypher at the foot of the design. To the right, we see the King’s Observatory in Richmond Park erected by George to observe the transit of Venus in 1769, which George and Charlotte duly did on the 3 June. The presence of livestock in the foreground gestures to the agricultural interests that won the king the soubriquet ‘Farmer George’. On the left we see Windsor Great Park, with in the foreground the ‘copper horse’ statue of George III erected on Snow Hill in 1831 following a commission from George IV to Sir Richard Westmacott in January 1821. As well as thus offering a palimpsestic acknowledgement of the earlier marking of the king’s death, this recognises Windsor’s central place in George’s staging of the monarchy, and its role as a home where the castle’s imposing presence (though less imposing than it now is following George IV’s redevelopment) belied its capacity to support the domesticated version of royal family life and the pursuit of the full range of pleasures of the country gentleman the king favoured. As a whole the design offers a view of the king as enlightened and improving, offsetting the classicism of the portrait bust at its heart: Evans notes that she ‘felt it important to add symbolism reflecting the life of a king and the mind of a man who was dedicated to discovery and progress’ (as quoted in the Royal Mint packaging for the 2020 coin).

In 1820, the designers of the commemorative medals had similar decisions to make, though more immediately constrained by the established conventions of medallic art of the time. Several fine examples survive in the Royal Collection (all, curiously, the gift of Ida Macalpine and Richard Hunter, the mother and son team of psychiatrists who first put forward the theory that George’s mental illness was the result of porphyria) of the more than ten medals that, according to one leading authority, Christopher Eimer, were struck for the occasion.

The same Thomas Wyon who had engraved the ‘Bullhead’ portrait produced a 4cm medal [fig. 5] noting the date of George’s accession around a profile portrait of the king in the prime of life and ‘modern’ (if not truly contemporary) dress, the reverse bearing an elaborate composition illustrating the biblical passage from Matthew 25:21 ‘Enter thou into the Joy of thy Lord’ from the Parable of the Talents. We see an image of a classically garbed crowd of onlookers observing an ascent into heaven in a fiery chariot of a figure – identified in the Royal Collection Trust catalogue entry as the prophet Elijah (who was indeed conveyed heavenward in such a vehicle), but which the crown on the passenger’s head surely suggests is the king himself.

Figure 5: Thomas Wyon the elder: medal commemorating the death of King George III, 1820. RCIN440013: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020

A second medal of roughly the same size was produced by Sir Edward Thomason (1769-1849) and Charles Jones from their jewellery and medal-making shop in Birmingham and engraved by John Marrian [fig. 6]. The son of a Birmingham bucklemaker, Thomason had served an apprenticeship with Matthew Boulton before setting up in his father’s factory to produce fancy buttons.Thomason had branched out into medal and token production in 1807, going on to manufacture long series of medals based on the Elgin marbles and historic events (his entrepreneurial imagination being apparent in his speculative decision in his first year as a medal producer to strike 5,000 medals bearing the first speech of Henri Christophe to the people of Haiti for despatch to the new president). In Thomason’s medal, George appears in profile in armour and cloak with his name in Latinate form, the reverse showing Britannia putting aside her spear and British shield to mourn the king alongside a lion, the crowned corpse being visible in a classical tomb above his dates of birth, accession and death.

Figure 6: John Marrian for Thomason and Jones of Birmingham: Medal Commemorating the Death of George III: RCIN440014: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020

Figure 7: Küchler’s ‘antique’ portrait of George III for the 1797 copper ‘cartwheel’ coinage issued in 1797 by the Soho Mint (Image by Heritage Auctions, HA.com)

A third and much finer bronze medal [fig. 8], almost 5 cm in diameter, is attributed in the Royal Collection Trust catalogue to the German-born engraver Conrad Heinrich Küchler (c. 1740-1810), the house medal engraver of Matthew Boulton’s Soho Mint in Birmingham, for whom he produced both coin dies and some thirty medals, his work including the bust of George for the famous ‘cartwheel’ coins [fig. 7]. Here George appears in a cuirasse again, with a latin inscription describing him as king and defender of the faith; the reverse sees a palm wreath surrounding another latin inscription giving dates of birth, accession and death, under a moto of “Pater Patriae” (Father of the Country). The attribution here is obviously problematic given that Küchler predeceased George by ten years, but the portrait bust is indeed by Küchler, bearing his initials, and was made from a die used in Küchler’s medals commemorating the victories of the 1798, the Union of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801 and the Peace of Amiens in 1792, which J. G. Pollard argued was executed as a bust ‘in the modern style’ in 1800 (his design for the cartwheel coinage, in contrast, being in the ‘antique’ style, despite the modernity of the innovation this copper coinage represented in terms of British currency).

Figure 8: Medal commemorating the Death of King George III, with Küchler’s ‘modern’ portrait of the king: RCIN 440038. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020

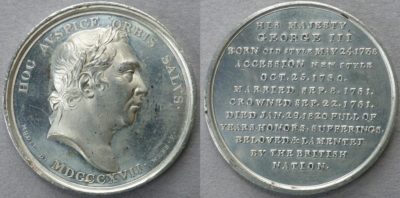

A very striking medal of 4.12 cm diameter came from the former marine and future Australian landowner Major James Mudie (1779-1852) and engraver Thomas Webb (1769-1822) [fig.9]. Here George appears in a decidedly ‘antique’ wreathed portrait by Webb, with the motto ‘Hoc auspice orbis salus’ (hard to translate precisely, but the thrust being ‘The augur of the world’s prosperity’). The reverse carried a long text giving dates of birth, accession, marriage, coronation and death and the observation that the king died ‘full of years, honors, sufferings, beloved & lamented by the British nation’. The date of 1817 on the obverse reflects the fact that the portrait was borrowed from another medal commemorating George III that Mudie also issued in the same year [fig. 10]. This was part of his financially ruinous speculative commission for various artists to produce a subscription series of forty ‘national medals’ struck at Thomason’s factory in Birmingham. These were sold as a boxed set (20 guineas if in bronze, 40 if silver, and 600 if gold) and individually, and commemorated chiefly events and personalities of the French Wars. On this version the reverse (by the French engraver Alexis Joseph Depaulis, 1792-1867) carried an image of figures ‘personifying Religion and Faith, or Honesty. These, in union with the rock behind the cornucopia and rudder, imply that Religion, Integrity, and Constancy, have steered Britannia successfully through all her dangers up to the present period’ (An Historical and Critical Account of a Grand Series of National Medals, 7).

Figure 9: Medal commemorating the death of George III designed by Thomas Webb, 1820. RCIN 440016. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020

Figure 10: Reverse of Medal I of Mudie’s National Medals, 1820 by Webb and Depaulis (Image: Le blog de spade-guinea-george-iii.over-blog.com)

Finally, another medal [fig. 11], whose creator is not clearly identified, is smaller in size (2.66cm diameter) but survives both in bronze and in silver. Here an older king’s portrait bust appears in the Windsor uniform introduced by George III in 1777 for use by the court with details of his birth, accession and death surrounding it. The reverse has a simple wreath surrounding the text ‘He has run his course and sleeps in blessings’, a quotation from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII from a scene (act II, scene III) where Wolsey responds to news from Cromwell of Sir Thomas More’s appointment in his place with a reflection on how posterity will view the latter after his death.

Figure 11: Unknown: Medal Commemorating the Death of George III, 1820: RCIN440017: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen, 2020

This group of medals sat at the end of a long succession of commemorative medals issued over the course of George’s reign. Even if one omits the significant number that referred to events and matters in which the king had no personal involvement, and concentrates only on those which had reference to his own life or opinions, the list of occasions so commemorated is striking. Christopher Eimer records for example medals relating to the following: the accession of George III (3); George as ‘protector of the arts’, 1760 [discussed above, fig. 3]; the marriage of George and Charlotte, 1761 (3); the coronation of George III (4) and of Charlotte (1); Charlotte’s 18th birthday, 1762; the birth of George, prince of Wales, 1762 (2) and with that of Frederick, 1763; the death of Princess Augusta (his mother), 1772; George’s recovery from illness in 1789 (4); his preservation from assassination in 1800; two portrait medals marking the new century in 1800; his recovery from illness in 1801; the royal visit to Weymouth in 1805; the jubilee of 1809-10 (4); the appointment of the Prince Regent 1811; and a family portrait celebrating the centenary of the House of Brunswick, 1816. Alongside the recoinages of the reign this offered a rich context of numismatic narrative to which the medals relating to George’s death provided a flourish as a finale.

What might we make of the iconography and texts employed in the medals relating to George’s death? In their detailing of his vital and regnal dates they emphasised, perhaps, the importance of the reassuring political and constitutional stability and personal steadfastness that George’s reign as ‘Pater Patriae’ had come to represent by 1820 for the propertied classes likely to purchase such objects. Many of them had lived through the American and French Revolutions, the threat of invasion and national humiliation present during the French Wars, and the radical challenge embodied in Peterloo the year before (there is no cap of liberty on the Britannia lamenting the king in Marrian’s medal, in contrast to the Britannia who adorned Jakob Abraham’s medal for the royal wedding of 1760); their parents and grandparents had experienced the Jacobite challenge of the 1740s. The medals here picked up a theme already articulated in the jubilee celebrations of 1809-10. While it is clear that there were plenty who took a less benign view of the sovereign, this aspect chimes well with Linda Colley’s important argument about the ‘apotheosis’ of George III from the middle period of his reign, which saw a monarch controversially enmeshed in political competition in the 1760s-80s emerge after his bout of illness in 1788-9 as a symbol of national unity enjoying a significant degree of popularity, not least because he was no longer such an active force in partisan politics. It was of course not for want of trying that the identification of George with the British nation had taken time, and the medals focused on the king’s person throughout his reign bear witness to an effort to promote such an equivalence, not least in the absence of direct reference to his other dominions, notably Hanover, but equally the colonies. It added an extra dimension to this vision that George had not merely survived so long, but had suffered so much along the way: here the inscription on the Webb/Mudie medal is particularly telling, which could be read as referring to his illness, his familial bereavements and quarrels or his political setbacks, or equally to all three.

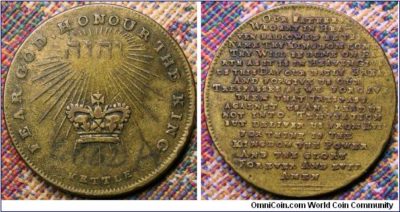

A second striking feature is the strong Christian element to the iconography, in marked contrast to the wholly secular 2020 coin. The point is reinforced by details of two medals not in the royal collection. The first (British Museum 1870,0507.16077), was by Thomas Kettle (d. 1829), a die-maker of Huguenot stock yet again working in Birmingham. This 2.5 cm medal offered a portrait of the king with the motto ‘God protects the just’, and on the reverse the key regnal dates. The image of the king with this motto had been used by Kettle in a medal for his jubilee, and another version (British Museum 1945,1102.1), associated with the king’s death in the catalogues but with no such indication on the object itself, replaced his regnal dates with a striking design of the crown illuminated by rays emanating from the name of Jehovah in Hebrew with the injunction to ‘Fear God and Honour the King’ (1 Peter 2:17) which in turn in another medal (BHM# 996) accompanied the full text of the Lord’s Prayer [fig. 12]. The second, for which no illustration has been found (British Museum M.5643), bore the inscription ‘THE KING EXPRESSED A WISH THAT HE MIGHT LIVE TO SEE THE TIME WHEN

EVERY POOR CHILD IN HIS DOMINIONS COULD READ THE BIBLE’. Together, these serves as a useful reminder of the significance of George’s personal piety, which historians in recent years have begun to re-emphasise both as a vital context for understanding his actions in other fields and as one basis for loyalty to him among the majority Anglican population in England. The title of ‘Defender of the Faith’ in the Soho Mint medal was more than a courtesy when applied by protestants to the king who had so staunchly opposed Catholic Emancipation in the first years of the nineteenth century. The sense that the king was going to his deserved heavenly reward was probably a common one among militant protestants and not just in the established church as its missionary efforts directed both to the heathen and the Irish catholic community were gathering pace. The themes of Christian commitment and national alignment came together in Mudie’s coin, with its insistence that ‘Religion, Integrity, and Constancy, have steered Britannia successfully through all her dangers’, and also in Wyon’s, with its quotation from the parable of the talents, a key biblical discussion of stewardship.

Figure 12: Thomas Kettle, commemorative medal for the death of George III: British Museum catalogue 1945,1102.1; image Omnicoin.com

Thirdly, we might note the variations in the portrayal of the king himself on these coins. These obviously exist in the context of well-established traditions of numismatic portraiture, and owe something too to the costs and risks entailed in creating new images rather than reusing existing ones which should make one wary of reading too much into archaism. Nevertheless they capture something of the way George’s reign lies on the cusp of the modern era. Merely within the medals associated with his death we see three types of image: a consciously ‘ancient’ portraiture drawing on the conventions of classical imagery; a ’modern’ form which in fact in its use of cuirasses and cloaks harks back rather to an ‘early modern’ European model of military monarchy; and, in the anonymous cheaper medal depicting the king in the undress Windsor uniform, some hint of a different understanding of cultural authority in an age which would see statesmen as well as monarchs adapt the conventions of dress associated with the ruling class, and which formed such a striking aspect of the public image of George III as farmer or pater familias that was a novelty of his reign.

Finally, a twenty-first century audience will of course note the obvious absences from the representations of George III on these celebratory medals and coins: the dark underbelly of slavery, gender and class inequality, brutal militarism and aggressive cultural and geopolitical imperialism that sustained the Hanoverian monarchy and its ‘enlightened’ court culture. Here the 2020 coin is equally silent to those of 1820. While the absence is perhaps inevitable, it should none the less remind us of the importance of ensuring that in more appropriate fora these important dimensions of George III’s situation are given due weight as in Kara Walker’s spectacular and thought-provoking play on a different form of commemoration of George’s grand-daughter Queen Victoria, her installation Fons Americana at Tate Modern in London, on display until April 2020.

Further reading:

An Historical and Critical Account of a Grand Series of National Medals. Published under the Direction of James Mudie, Esq. (London, Henry Colburn, 1820).

Lawrence Brown, British Historical Medals 1760-1960, vol. 1 (London, Seaby, 1980).

Linda Colley, ‘The Apotheosis of George III: Loyalty, Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820’, Past and Present, 102 (1984), 94-129.

Christopher Eimer, British Commemorative Medals and their Values (London, Seaby 1987). A new edition was published by Spinks in 2010.

J. G. Pollard, ’Matthew Boulton and Conrad Heinrich Küchler’, Numismatic Chronicle, 10 (1970), 259-318