1. First evidence? Spring, 1765

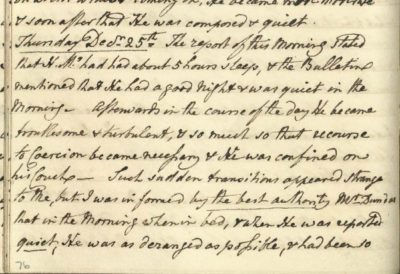

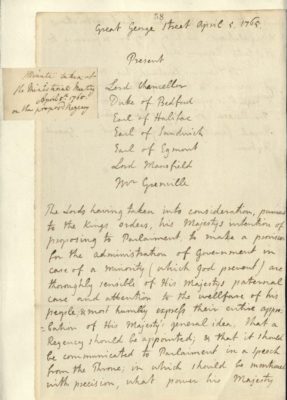

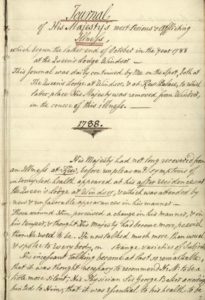

GEO MAIN/58: Minute taken at the Ministerial meeting of April 5th, 1765 on the proposed regency

Interpretations of King George III’s mental illness have regularly referred to a period in the spring of 1765 when the king may have been suffering from a combination of upper respiratory illness that triggered a depressive episode. The importance of this early episode is in suggesting a lifelong condition. The evidence consists of reported symptoms including cough, fever, and weight loss, along with acute sleeplessness and some cognitive impairment.

Probably the most important indication of the seriousness of this episode, whether physiological, psychological or — as seems most likely — a combination of the two, is that the king moved to put a regency bill into effect.

GEO MAIN/58. To see a high definition image of the whole document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here. For a transcription, click here.

In this document, a ‘Minute taken at the Ministerial meeting of April 5th, 1765 on the proposed regency’, the king’s desires are noted: to direct that a regent be appointed of his choosing, with specific, limited powers, and ‘resident in Great Britain’. In the resulting ‘Minority of Heir to the Throne Act’, Queen Charlotte or the king’s mother would act as regent while his children were in their minority. The act refers to ‘your Majesty’s late Indisposition (which filled the Breasts of all your Subjects with the most alarming Apprehensions)’ and which ‘had led your Majesty to consider the Situation in which your Kingdoms and your Family might be left, if it should please God to put a Period to your Majesty’s Life, whilst your Successor is of tender Years.’

A regency was debated multiple times during George III’s reign. Regency was seriously considered during 1788-89, and in the last decade of the king’s life, 1810-20, when his illness debilitated him entirely, the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, finally became Prince Regent.

2. A Doctor Writes

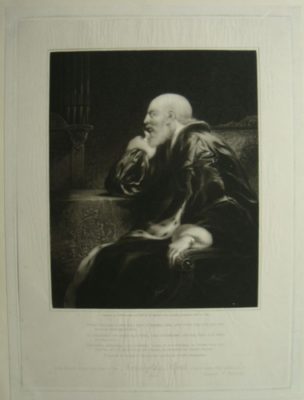

MED 16/14, 78-80: Doctors’ reports on the king’s condition to the Prince of Wales, 25 December 1788 and 15 February 1789

Among the most important medical papers held in the Georgian paper archives are the daily bulletins written for the Prince Regent by the team of doctors who treated George III for his various episodes of mental illness (MED 16). These are not the only records the medical team left behind — equally important are similar bulletins sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury for the Queen’s Council after 1810, held at Lambeth Palace Library, and there are verbatim records of the examination of the doctors in parliament from 1788, 1789, 1810 and 1812. The Willis family papers in the British Museum contain a variety of materials relating to the several Willises involved in George’s care, while diaries survive for Henry Halford, George Baker as well as for Willis, and there is much additional correspondence between the physicians and the court and politicians.

The reports in the Royal Archives are uniquely valuable, however, in charting the day-by-day perceptions of the king’s condition from those best placed to observe him with some degree of medical insight (though the familiarity of the various physicians with mental disorders varied greatly). They have also been used in historical studies since they were first consulted in the 1930s by Manfred Guttmacher to furnish details of the treatments the king underwent, and of the specific physical and mental symptoms the king exhibited, providing the basis for accounts of the trajectory of the king’s illness and the impact of treatments which some historians have argued themselves may have contributed to his suffering.

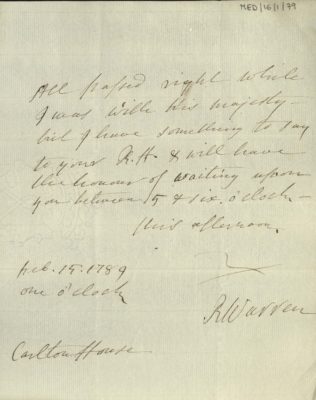

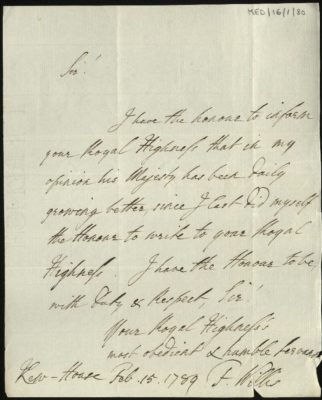

MED 16/1/78-80: Two reports for 15 February 1789 from the king’s doctors. To view high definition images of the February 1789 letters click on the images. For a transcription, click here. To read the catalogue entry, click here

The extracts chosen here highlight two other important themes illuminated by a close reading of these documents. Many of the documents were signed by all the doctors with the king on the specific day in question but at points one or other might break ranks and offer in effect a ‘minority report’, either offering a very different account of the previous 24 hours, or a different reading of the implications of various events. Far from raw medical reports of dispassionate physicians, these documents exhibit the impact of the complicated politics of the king’s illness and consciousness of the implications of the reports in terms of lending support to the competing arguments for and against the regency taking place in Westminster and the court. But even when the doctors presented a united front, historians face a challenge in determining how to weigh up the relative value of these ‘official’ and ‘of the moment’ documents against contradictory evidence in memoirs and diaries.

Thus MED/16/1/79 and 80 are two individual reports sent to George, Prince of Wales on 15 February 1789 from Richard Warren, the doctor assigned to George on the Prince of Wales’s initiative and with close ties to the whig circles seeking an active regency, and from Francis Willis, the doctor most closely associated with the more favourable prognosis that suited Pitt’s ambitions of avoiding this if possible. They clearly exhibit marked differences of tone.

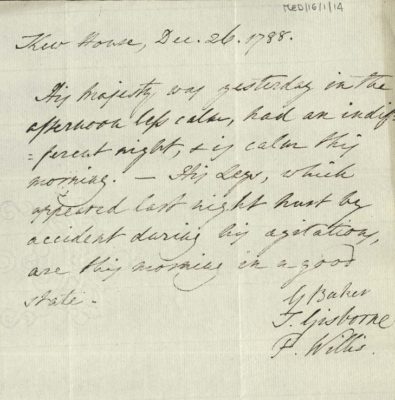

RA MED/16/14, Doctors’ report to Prince of Wales on the morning of 26 December 1788. To read all the doctors’ reports for this period in high resolution, click on the image. For the catalogue entry click here. For a transcription click here.

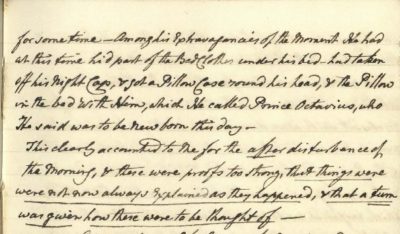

Then the third example (MED 16/1/14) is in fact one of the less laconic examples of a collective report, that for morning of Boxing Day in 1789 recounting the king’s condition on Christmas Day. Yet reading it alongside Robert Fulke Greville’s account of the same 24 hours, preserved in his diary of the King’s illness, makes clear that either the doctors were drawing a discreet veil over the king’s behaviour whether for political reasons, questions of taste, or to protect their own professional reputations, or that Greville was recounting wild gossip from Kew.

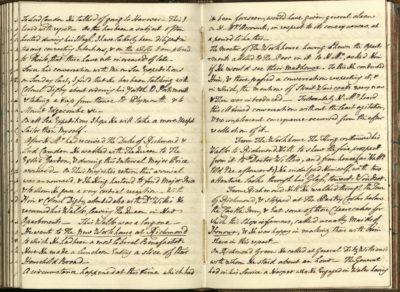

Excerpt from Greville’s journal for 25 December 1788. To see the whole journal in high resolution, click on the image. For a transcription, click here

3. A sympathetic observer

RCIN 1047014: Journal of Robert Fulke Greville. Volume 2, Oct. 1788 – 4 Mar. 1789: first page and entry for 3 March 1789.

Robert Fulke Greville (1751-1824) was the second son of the Earl of Warwick, who embarked on a military career after studying at the University of Edinburgh. By 1777 he was a lieutenant-colonel in the 1st Foot Guards, a position which he combined with serving as member of parliament for Warwick 1774-80 who aligned himself with Lord North’s government; then in 1781 he took on the role of equerry to George III, a post he was to retain until 1797. He seems to have been a popular figure at court, Fanny Burney nicknaming him ‘Colonel Well-Bred’.

Today, Greville is remembered chiefly as the author of a memoir devoted to recording the king’s illness in 1788-9. Unlike many of the memoirs and reminiscences which the first historians of George’s illness drew upon as sources, Greville’s was published more than a century after his death, first becoming available to the public when F. McKno Bladon published an edition of the diaries in 1930. Manfred Guttmacher was thus the first important biographer of George to be able to make use of the source, and it played an important role in enabling Charles Chevenix Trench to write his narrative of the king’s illness of 1788-9, The Royal Malady, in 1964.

Greville’s diaries are immediately attractive as a source to the historian for a number of reasons. The equerry was close to the king, and unlike the doctors whose daily reports are the other most immediate source for the progress of his illness, he was not constrained either by the political calculations which we have seen potentially compromised their ability to be entirely honest about their assessment of the king’s condition, or by the professional protocols of physicians writing official reports which even then encouraged a laconic approach with a minimum of emotional colouring. Greville in contrast wrote as a medically unqualified but highly interested observer of his sovereign’s distress and humiliations, given to discursive and sympathetic reflections on the impact not just of the illness, but of the treatments on the royal patient. That said, historians need to guard themselves against succumbing too readily to the seductions of so readable and quotable a source. For significant periods (both in time and importance) Greville was not with the king, and was reliant on secondhand reports as much as other memoirists. He had his own biases: he seems not to have liked the Queen, and was wary of Pitt (being related to leading opposition figures) and of Willis, whom he found coming between him and his monarch. He clearly felt for the humiliations and pain visited by physicians on the patient; but it is not clear how far this was a reflection of a sense that it this constituted inhuman treatment, or rather a sense that treatment that otherwise might not have provoked comment should not be visited on a monarch. And there still remains a question as to why Greville decided to keep this journal if he did not envisage it being read by others at some future date.

The first page of Greville’s journal.

As long as such caveats are borne in mind, and Greville’s journal not just assumed to be a ’better’ record than other less forthcoming accounts, however, it remains an invaluable and moving testimony as to what it was like to live through the king’s illness at close quarters, recording strains and stresses on the family and the monarch that other sources clearly felt constrained to omit.

Here we show two excerpts from the journal (a third short extract, detailing a ‘bad day’ for the monarch at the height of his illness on 25 December, has already been discussed in reference to the doctors’ reports). The first is the opening page, which indicates the care which Greville lavished on the document’s production. The second comes from the entries relating to the period of the king’s recovery, on 3 March 1789, exemplifying Greville’s sympathy for his monarch and evident pleasure in his improvement, recounting the visit of the king to Richmond asylum, and his unanticipated encounter there with an example of one of the disciplines to which he had been subjected during over the past few months: the straitjacket. In observing that the king undertook a conversation about the jacket with equanimity and his formerly characteristic interest in how things were done, Greville clearly enjoyed being able once more to respond admiringly rather than pityingly to his sovereign.

Robert Fulke Greville’s entry for 3 March 1789. To see in high resolution, click on the image. For a transcription, click here. For the catalogue entry, click here

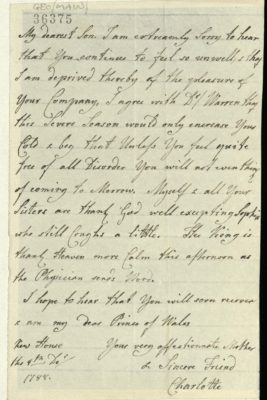

4. The Queen’s Secret Terror

To read the full letter in high definition click the image For the catalogue entry, click here; for a transcription, click here.

Among the challenging features of interpreting the king’s mental illness is getting a clearer picture of his family during his most acute episodes. In this letter of early December, 1788, when other evidence suggests the king was in such a terrible — and declining — state that within days a new doctor (Francis Willis) was called in to attend the case — the Queen writes to her eldest son, the king’s heir, that ‘the King is thank Heaven more Calm this afternoon’. This is a remarkably understatement. The king’s had only just been removed from Windsor to Kew, and his family essentially banished from interacting with him.

For any number of reasons the Queen might have been treating the Prince of Wales carefully. The question of a regency was fraught, and the political implications profound. Antagonizing the Prince, whose political sympathies were well known to be opposed to his father’s — and those of the Prime Minister — was the last thing she would want to do. Carefully attentive to the politics and diplomacy of monarchy, well read in the history of reigns gone awry, the Queen would have wanted to keep her family intact — and that meant keeping her husband’s capacity to rule intact, even while his mental capacity seemed limited at best.

The other feature of this letter, and of any direct information from the Queen during the king’s most acute episode of mental illness, is the absence of any recognition of how proudly his condition affected her. From the diaries of Frances Burney we can learn how profoundly distressing the king’s condition and behaviour were for the Queen, and for her children. Burney used the word ‘horror’ repeatedly to describe the Queen’s situation. The doctors attending the king tended to disregard the Queen in their reports, preferring to treat the king alone and only obliquely acknowledging why.

A key reason for the Queen’s horror, and for the doctor’s decision to separate the king from his family, was evidence of what ranged from complete sexual disinhibition to sexual aggression. In Bennett’s play the king’s attention to the Countess of Pembroke is played for nervous laughs. But the record of the king’s behaviour in 1788-89, and again in 1804, was anything but funny. By one report he assaulted both his eldest daughter, and his daughter-in-law. On one occasion he ran naked into the Queen’s chamber, threw her on the bed, and demanded that her ladies evaluate his sexual performance. One report suggested he suffered from priapism (a medically dangerous, persistent erection); it is possible that he was simply observed aroused, which was shocking enough. These accounts all came from members of the court. In late 1804 Lord Malmesbury reported that ‘The Queen will never receive the King without one of the Princesses being present … and when in London, locks the door of her … room against him.’

The evidence of sexual violence, in a culture already shaped by hierarchies of gender and class in which women’s power — even the Queen’s — was limited, casts a different light not only on the episodes of the king’s mental illness, but the ways that the court and doctors interpreted his behaviour. Gender and sexuality were already bound up in the expectations of the monarchy. Producing heirs, after all, was a key responsibility. George III’s carefully cultivated reputation as a sober, serious family man was at odds with the behaviour he exhibited when he was most ill. As he re-entered society, with his family by his side, it was that reputation which may have been, for those who knew him best, most challenging. They, too, were recovering from traumatic experience.

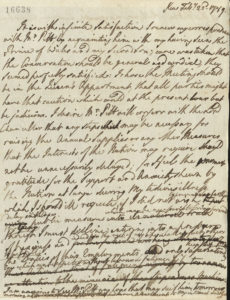

5. A draft memorandum by George III regarding the renewal of correspondence with Prime Minister William Pitt, 23 February 1789

GEO/MAIN/16638

To read in full in a high-resolution image, click the document. For a typed transcript, click here.

With this draft letter of 23 February 1789, which we also included in our exhibition for Mark Gatiss, George III resumed the correspondence with his prime minister, William Pitt the younger, which had been interrupted by the illness from which he was now recovering. As we observed when presenting it then, it speaks to a number of key points in our understanding of the impact of George’s illness both on the king himself and his relationship with the state over which he presided, and, in its numerous corrections and deletions, to the difficulty the king found in articulating what he wanted to say.

We would reiterate the points made before about the way the letter illustrates the resilience of the king in seeking to move beyond the impact of his illness and to face up to the need to conduct business on a rather different basis going forward, but it is also worth emphasizing that this resilience was also underpinned by the king’s enduring sense that events were governed by a divine providence that could not be second guessed or resisted, but rather must be accepted. This was a perspective shared equally by the Queen and which was an important frame for their experience of a full range of vicissitudes both public and — as here, or in the infant death of Adolphus and Octavius — private.

The letter also speaks directly to the concern voiced not only by contemporary politicians but by later psychiatrist-historians such as Isaac Ray and Manfred Guttmacher, about the particular issues that arose when a monarch or other leading political figure should appear to have lost command of their faculties — how could the polity which they served be protected?

There is also a particular poignancy in the exchange for those who know the history of Pitt’s father, William Pitt the elder, one which Alan Bennett picked up on and employed in the scene in Part II of his play where George, Willis and Pitt meet at Kew, and Pitt recalls his experience of his own father’s mental illness. For much of the time when he was nominally leader of the Chatham ministry in the late 1760s William Pitt the Elder was incapable of dealing with business or meeting with king or colleagues, fatally compromising the effectiveness of his government. Did the king recall this when writing this letter?

Occasionally one encounters naive connections being made between the two best known facts about George III: that he was mad and that he lost America. But if mental illness contributed to the loss of the colonies in any way, that mental illness was Chatham’s not George’s. And George and Chatham were not alone among the ruling elite of the late eighteenth century in their experiences as statecraft became ever more demanding and statesmen ever more accountable for their decisions.

6. Service of Thanksgiving 23 April 1789

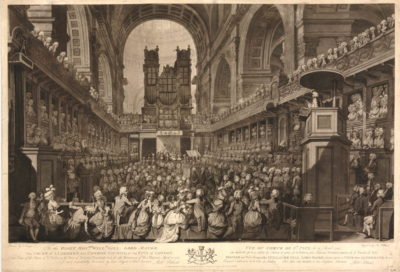

‘View in St Paul’s Cathedral looking towards the organ, a large congregation assembled in the presence of HM King George III at service of thanksgiving for his recovery, seated in box with members of the royal family in the centre, the Bishop of London in pulpit in the right foreground, his hand raised as if to silence the chatting crowds; after Edward Dayes. 1790 Aquatint, etching and engraving’ © The Trustees of the British Museum

One measure of the attention paid to addressing public concern for the king’s health is the fanfare surrounding his recovery. While the king was ill, public prayers were offered for his recovery. In November 1788 the Archbishop of Canterbury had required a prayer for the king’s health be added to the liturgy. As the king began to recover, in late February and early March 1789 the archbishop added a prayer of thanks. Following these moments of recognition that the king’s condition affected the entire nation, an elaborate service of Thanksgiving was arranged for 23 April 1789 at St Paul’s Cathedral. Thousands of people participated in this pageant, heralding the king’s return to health and to his place at the head of his family and his kingdom.

The scale of the Thanksgiving event surely reflected the enormous anxiety, familial and political, associated with the king’s illness. The morning began with a grand procession of the House of Commons, peers, judges, and more travelling a route through London, from Westminster to St Paul’s. At Buckingham Palace (the Queen’s Palace as it was known then), King George, Queen Charlotte, and their family joined at the very end of the procession. The service itself, at which a choir of 5,000 children sang the 100th psalm, lasted more than three hours. Celebrations continued into the next evening. The service was memorialized by artists, including Edward Dayes in the painting on which this print is based.

During this period of recovery celebration, including the Thanksgiving service, commemorative mementoes were made and gifted. Queen Charlotte, Frances Burney noted, ‘graciously presented me with an extremely pretty medal of green and gold, and a motto, Vive le Roi, upon the Thanksgiving occasion, as well as a fan, ornamented with the words — “Health restored to one, and happiness to millions”.’ Other extant of these fans echo that motto. These fans may have been created for a celebratory gala at Windsor on 1 May 1789, hosted by the king’s eldest daughter. Just a month later, the king bestowed on her the title of Princess Royal.

This fan from the Royal Collection Trust is one of a number of such fans that survive. Another can be seen in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, with the motto, but with two banners framing the crown cypher, and rose of England and thistle of Scotland.

7. Picturing the ‘Mad’ King

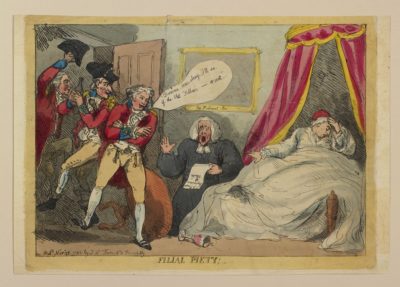

Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827): Filial Piety! 25 Nov. 1788. The only known satirical cartoon depicting the King during his illness of 1788-9. The Royal Collection Trust: RCIN 810287.

Anyone who has seen a good production of Alan Bennett’s play The Madness of George III (not least that at Nottingham Playhouse in 2018) or the film version directed by Nicholas Hytner with its virtuoso performance from Nigel Hawthorne as the king, will have a very clear image of the ‘mad king’ imprinted in their memory. This can perhaps serve to obscure the fact that otherwise we have very few ways of picturing George III in his illness without such cultural mediation. In a curious way, even when we do have such an image, it can be difficult to ‘see’ it without consciously or unconsciously picking up cultural references which can sway our understanding.

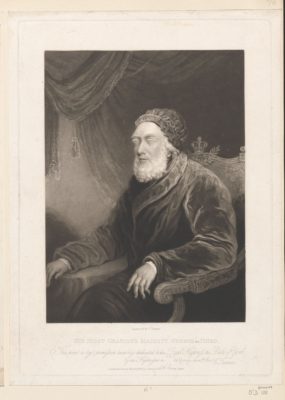

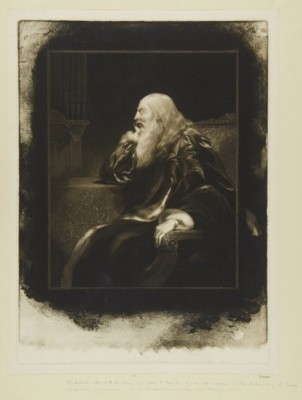

Samuel Reynolds’ mezzotint of George III, before and after modification, c. 1820. Royal Collection Trust RCIN 604480 and RCIN 604483. Click on images to see in high resolution

Probably the most familiar image we have of the king when incapacitated by illness is the mezzotint created by Samuel William Reynolds c. 1820 from sketches by Matthew Wyatt, which was only released once the image had been modified and made less ‘wild’. It is very hard to view the image as it was at proof stage without mentally relating it to the Shakespearian character of King Lear, not least because of the famous and poignant incident during the 1788-9 illness when King George was found reading the play ( reworked by Bennett into a moving but imaginary scene in which the King literally plays Lear – see an item in our earlier exhibition for Mark Gatiss for the doctor Lucas Pepys’ report on the incident). Other, less familiar images from the king’s last illness are if anything more distressing, but represent more his physical incapacities as he lost his sight and hearing than direct evidence of mental illness.

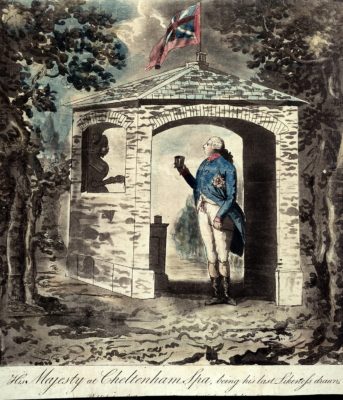

A third variety of depiction from this period represent more glimpses of the king snatched at a distance or imagined than portraiture, being the visual equivalent of passages in some memoirs from the time when the king was encountered by visitors to the terrace at Windsor.

King George III taking the waters at Cheltenham. Coloured aquatint by J.C. Stadler after C. Rosenberg, 1812.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Joseph Constantine Stadler (active 1780-1812), His Most Excellent Majesty, GEORGE THE THIRD, in the 74th Year of his Age & the 52nd of his Reign. 1812. RCT, RCIN 604470

Finally, there is the famous ‘bullhead’ image of George III by Benedetto Pistrucci which appeared on new coinage in 1816. It is a remarkable and slightly disturbing image — but did it in any sense represent an attempt consciously or unconsciously on the part of the artist to capture anything of the king’s condition?

In one sense, of course, it is hardly surprising that we do not have formal portraits of the king painted during an illness in which he was in seclusion. But it is perhaps more striking that there are not more instances of hostile images of the king portraying him as a ‘lunatic’ even if we turn to the most important earlier episode of the king’s illness, that of 1788-9. The late eighteenth century was a great era of political cartooning, by continental standard remarkably free from censorship, and with which those caricatured often had an ambiguous relationship, collecting caricatures of themselves. It was also a period in which the monarchy itself was frequently the object of hostile criticism from a small but vocal and growing body of radical critics. Yet we struggle to find caricatures of the ‘mad’ king. Perhaps the nearest thing is the satire which appears at the head of this item and exhibition, from 1788. Here the king is clearly suffering from something — but what the ‘old fellow’ is actually suffering from is obscured by the dash usually reserved to ‘hide’ the name of the person satirised in the most scurrilous prints. Moreover the portrayal of the king’s distress resists any temptation to depict anything more than resort to a sickbed and the concern of his chaplain for ‘restoration of health’. In this image, as in much of the satire published during the king’s last decade, it is clearly his son who is the main target of the criticism. In fact the only images that can be recovered explicitly referencing the king’s madness are those which were produced to celebrate his recovery in 1789, and here the king is portrayed in good health and in celebratory terms. The image of the ‘mad’ king remains tellingly elusive.

PROCEED TO HISTORIOGRAPHICAL TIMELINE