1. ‘A true Friend is difficult to be found’

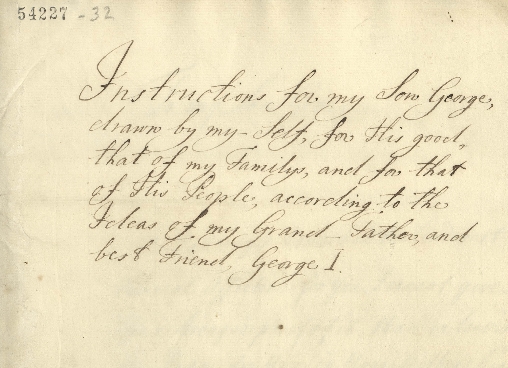

GEO/MAIN/54227-54232, 13 January 1749. Instructions from Frederick, Prince of Wales, to his son George

While father-son relationships were strained within the Hanoverian household, fathers were not uninterested in the education of their sons. Family letters show Frederick, Prince of Wales, taking a keen interest in the education of his heir, the future George III. In a highly personal document, Frederick gave his then 10-year-old son advice that would prove invaluable as he prepared to become king. Estranged from his own father, Frederick turned to the example of his grandfather, George I, as a model for kingship, and encouraged his son to do likewise. Tragically, however, Frederick himself would never assume the office of king, dying unexpectedly in March 1751, and his statement that he would ‘have no regret never to have wore the Crown, if you [George] do but fill it worthily’ proved eerily prophetic.

To read the rest of this document in high definition, click on the image. For a transcription, click here. For the catalogue entry, click here.

Hoping that his son would read the pamphlet ‘from time to time’, Frederick did not deliver a sermon to George, but instead offered friendly (and fatherly) advice. He asked that George should show the greatest respect to his mother and look after his siblings as though he was their father. Frederick went on to advise his son to live economically (a lesson George would fail to instil in his own son, the future George IV), and offered advice on matters of war and taxation, as well as giving guidance on how to deal with the Treasury. He warned his son that he needed to learn to trust to his own judgement, as ‘flatterers, courtiers, or ministers are easy to be got, but a true friend is hard to find’, implying the need to ris above party politics if he is to avoid being taken in by those seeking their own advancement.

The primary lesson the young royal was desired to learn was how to be a good man. After this, he was to learn his limitations, and to recognise the importance of asking for advice when required. While on the whole Frederick asked his son to follow the example of George I — particularly in relation to the managing of the twin kingdoms of England and Hanover — there are vagaries in his language that allowed George to carve out his own ruling style, independently of his great grandfather. For instance, Frederick urged his son not just to be ‘an Englishman born and bred’, but to be one by inclination as well —something that George I never really managed. Rather than by severing ties with Hanover, it was by education that George strove to become a true Englishman, learning more about the country of his birth and becoming more familiar with the nation’s customs than his forebears.

2. How to Educate a Prince?

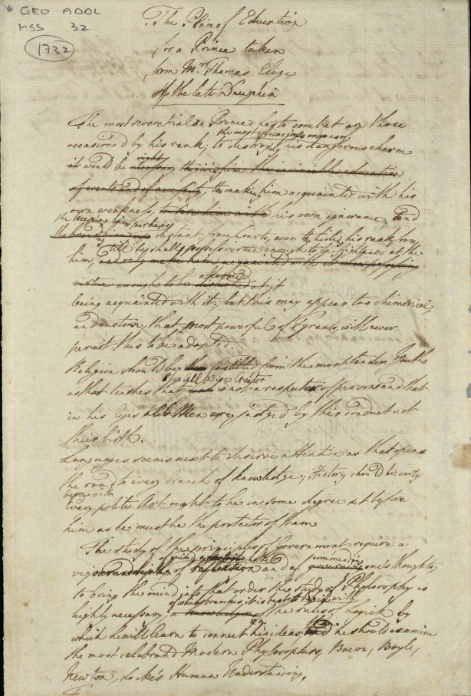

GEO/ADD/32/1732, The Plan of Education for a Prince taken from Mr. Thomas Eloge of the late Dauphin [1766-1805]

Source text: Antoine-Léonard Thomas, Éloge de Louis, dauphin de France, par M. Thomas (Regnard: Paris, 1766).

With the education of the Prince being in the national interest, it is to be expected that many papers within the ‘Essays’ are concerned with this crucial stage in George’s life. Papers such as ‘The Plan of Education’ address the education of a good man, and also consider how to make that man a good ruler. Educating the future monarch was no light undertaking, and so it is unsurprising that papers on the subject appear not just in George’s handwriting, but also in that of his tutor John Stuart, the 3rd Earl of Bute (1713-1792). Princes may have needed the same grounding in principles of mathematics, languages and natural philosophy as other young men of rank, but they also needed to grapple with another key area, namely affairs of state, and how these had an impact on their public and private concerns.

For a high-resolution copy of the whole document, click on the image. For a transcription, click here. For the catalogue entry, click here.

Across this series of papers written about the education of a prince, patterns emerge that provide a framework for understanding the educational agenda within the royal household. Languages, history, geography, a sense of chronology, morality and a religious matters are themes and topics that occur time and again. The ‘Plan of Education’, which is written in George’s hand, emphasizes that languages are the most vital skill to be learned by a prince, but also that ‘History should be early begun with [and] Every polite Art ought to be in some degree set before him as he must be the protectors of them.’ This interest in creating a historical education is reflected in ‘The Essays’ at large. Over 1,000 pages in the collection are given over to writing the histories of monarchs and European countries.

The ‘Plan of Education’ can, to a certain degree, be read back on to the ‘Essays’ to provide their rationale: the topics that are suggested for the education of a Prince reflect the content of this miscellaneous collection. The ‘Plan’, indeed, when taken with the ‘Instructions from Frederick’, and the ‘Sketch of the Education I mean to give unto my sons’ (GEO/ADD/32/1733), functions as something of a road map for navigating the diverse range of topics the ‘Essays’ address. The areas of study proposed in these papers directly correspond to the categories used in the modern catalogue, and there is evidence that some of the reading suggestions these paper make were put into practice. Writers identified in the ‘Plan’ — including Bacon, Boyle, Newton, and Locke — recur throughout the collection. They are either mentioned in passing, or their works are commonplaced (the process of extracting and copying of passages from published texts) at length, showing George’s engagement with prominent thinkers.

While the success of these plans for educating a prince cannot be ascertained, it does seem plausible that elements shaped George’s education and offer some rationale to explain why some ‘Essays’ have survived.

3. The Three Rs: Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic

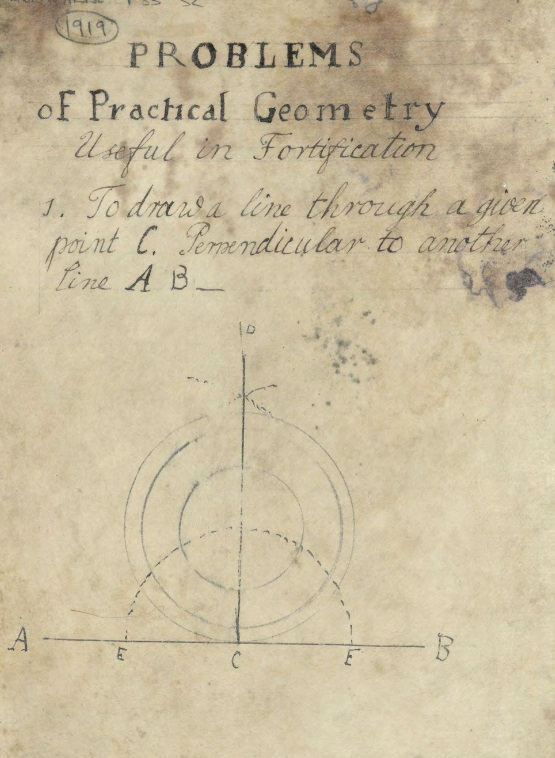

GEO/ADD/32/1919-1924 Problems of Practical Geometry [1746-1805]

Source Text: John Muller, A treatise containing the elementary part of fortification, regular and irregular. With Remarks on the Constructions of the most celebrated Authors, particularly of Marshal de Vauban and Baron Coehorn, in which the Perfection and Imperfection of their several Works are considered. For the use of the Royal Academy of Artillery at Woolwich. Illustrated with thirty-four copper plates. By John Muller, Professor of Artillery and Fortification (London, [1756])

Throughout the Georgian Papers we can see George III coming to terms with new topics, testing out new ideas, and learning by repetition. While a significant proportion of the paprrs in a youthful hand are either exercises in Latin or take the form of history essays, there are also several papers devoted to the study of mathematics. In these we find many topics that would not be out of place on a modern curriculum — fractions, algebra, trigonometry, and drawing circles. Yet there are also several papers that are less in keeping with a traditional education, particularly those concerned with the application of geometry and perspectival drawing to military matters.

To view a high-definition image of the whole document click on the image. To read the catalogue entry click here; for a transcription, click here.

Written in a childish hand, these papers reveal an early fascination with mathematics and science. Although mathematics is not one of the areas Frederick asked George to apply himself to, maths was a vital part of his wider education and practical understanding of constitutional affairs, particularly with regard to fortification and defence. Rather than learning geometry for geometry’s sake, the ‘Problems of Practical Geometry’ are subtitled ‘Useful for Fortification’. Pushing beyond the exercises typically asked of schoolchildren, these papers suggest how each part of a prince’s education was being adapted to equip him with practical knowledge that would help him to defend the kingdom should the need arise. Hence, questions of geometry are translated into practical defence and a knowledge of trajectories for missiles.

However, while papers such as ‘Problems of Practical Geometry’ can begin to shed light on the practical purposes of the education of royal children, this collection of papers raises more questions than it answers. Many of the maths papers are untitled and many of the perspectival drawings are loose, making it difficult to identify their context: the papers on the ‘Problems of Practical Geometry’, for instance, are catalogued as six separate items and we have little sense of to what, precisely, some of the latter drawings relate.

Such unknowns are symptomatic of the challenges raised by many of these more youthful writings as closer analysis of these papers has raised questions about their authorship. While these papers have historically belonged to the collection known as ‘The Essays of George III’, they are clearly not essays, and, as the handwriting is different from that in other papers, there is some speculation as to whether some of these juvenile papers are actually in the hand of a young George IV.

4. More Latin, Less Greek: amo, amas, amat

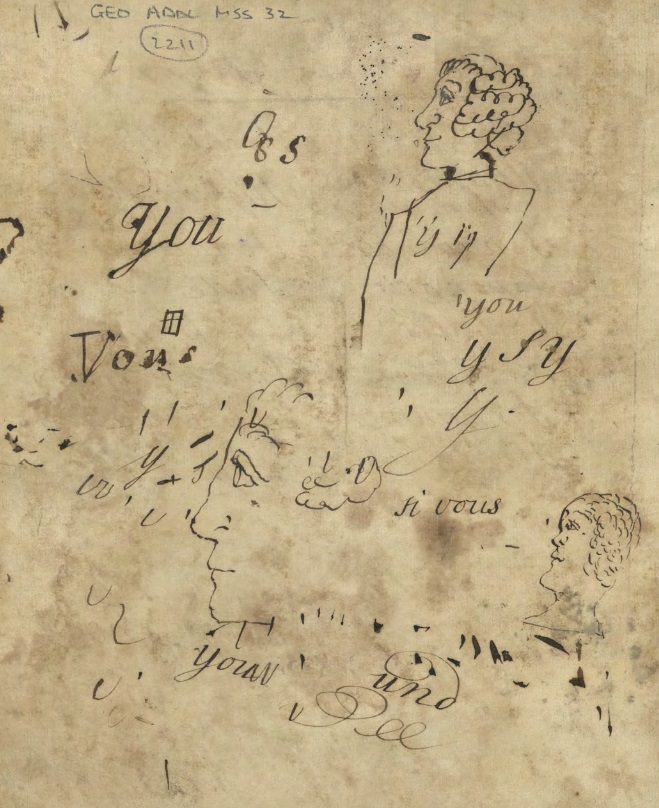

GEO/ADD/32/2211-2250, ‘Book of Latin Words and Phrases’ [1746-1805]

It has commonly been noted that the young George III was something of an errant student, never committed to his studies and having a short attention span. Within the series of papers originally catalogued under the catch-all title of ‘School Lessons’ we find various exercises in both mathematics and languages, showing the Prince as a teenager catching up on parts of his education that he had previously neglected — one of his Latin translations is clearly dated 9 July 1753, falling in the period before Bute was officially appointed his tutor in 1755.

For the full text in high definition, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here.

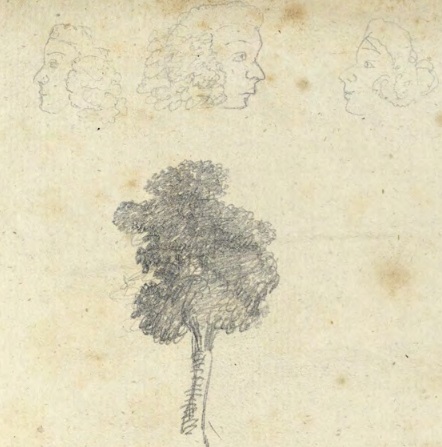

George’s books of Latin words and phrases are clearly schoolboy exercises and offer a list of words alongside their English translation. However, most pages are adorned with the idle penmanship of the uninterested scholar. The majority of these markings are simple line drawings, taking the form of scroll-like ornaments, or fleurons, of the kind typically found in printed manuscripts from the period, yet some are far more artistic. The doodles commence at the title page, which is adorned with idle pen marks and blotches. Yet in the Latin books we also find a series of Hogarthian-style doodles that show the young monarch being distracted from his studies — a trait that is replicated in other papers as we find further faces, trees, tankards and other idle drawings scattered throughout the ‘Essays’. Further faces are found at the back of a printed volume of 1774 archived among the Essays entitled An Account of a New Hygrometer — and two of these pencil drawings bear a remarkable resemblance to the pen figures in the Latin book.

5. The Business of State

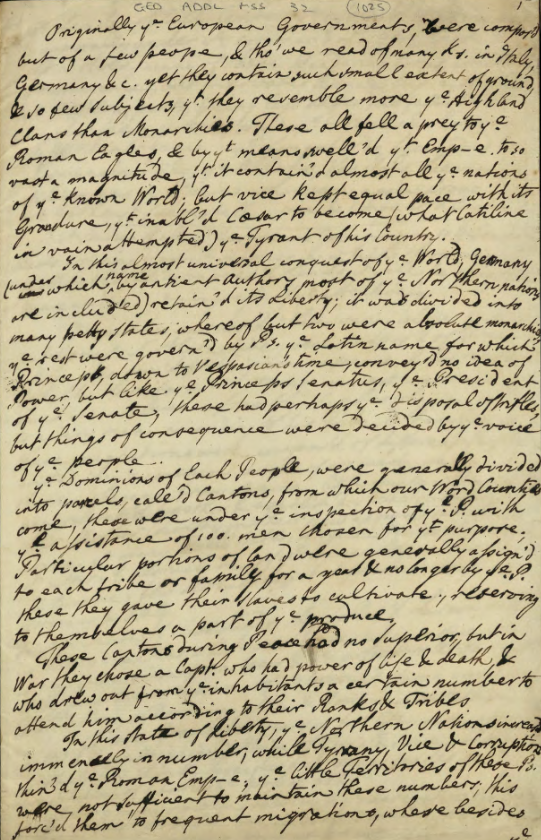

GEO/ADD/32/1025-1033 Draft essay on government [1756-1780]

For the full text in high-resolution, click on image. For the catalogue entry, click here; for transcription, click here

While many of George’s papers are the product of the enquiring mind of any young scholar, parts of his education are a direct result of needing to learn how to be an effective monarch. This is most evident in the series of papers on the government, the constitution, and on revenue and taxation. Many of these exist in a fair copy, with no corrections, suggesting that George copied these materials rather than commonplacing or (re)interpreting a printed work. While such a method may not be the most effective method of learning facts, engaging with government affairs in this way ensured that the future king had at least a basic familiarity with the events of each parliament since the time of the Glorious Revolution.

Among these state-oriented essays are a series of ‘Essays on government’. There are four items grouped under this heading — in fair and draft copies — and among the several crossings out and rewritings we can see the hand of Bute, guiding his pupil through the mire of political history. All these essays, comprising almost 400 pages of manuscript, address the nature of local government, both in England and in Europe, and pay particular attention to changes in government in the wake of the Saxon conquest, Norman conquest, and the imposition of the feudal system. Echoing the concerns of other parts of the collection, the essays on government dwell at length on the nature of tyranny, liberty, and the extent of legislative power, as George explores what courses of action are best suited to running and maintaining a successful government.

6. ‘Tuition fees’ – Costing a Princely Education

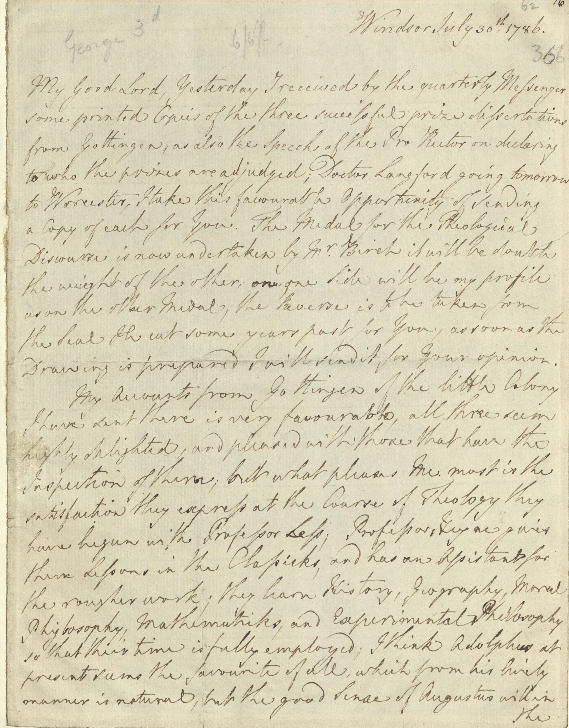

GEO/ADD/2/21 Letter from George III to [the Bishop of Worcester] 30 July 1786.

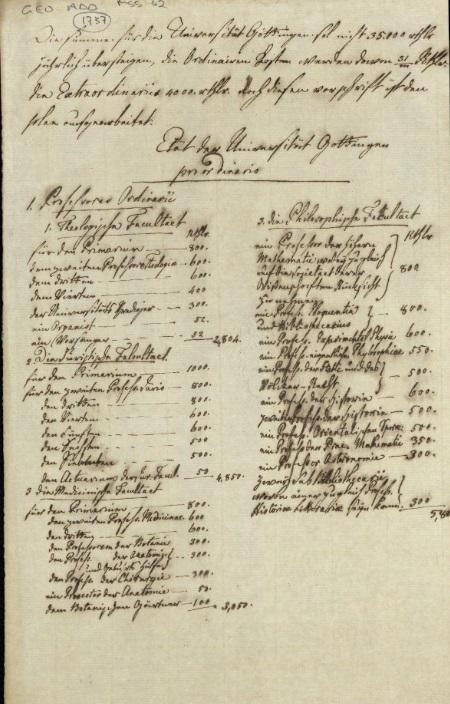

GEO/ADD/32/1737, Etat der Universität Gottingen pro ordinario [1746-1805]

GEO/ADD/32/1737. For a high-resolution image of the document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here.

Many of the papers that make up the ‘Essays’ take the form of memoranda, fragments, or notes that are undated and that are offered with little or no context. This makes some of them seem particularly eclectic, such as the papers relating to the finances of Göttingen University (GEO/ADD/32/1737, 1739). However, when set in the context of the Georgian Papers more broadly, some of these stranger essays take on new significance. In the case of the ‘essay’ on Göttingen, we find that the German university is the subject of letters George sent to his friend Richard Hurd, the bishop of Worcester, in 1786.

One of these letters tells of the arrival of three prize dissertations from Göttingen, of which George had the pleasure of enclosing copies with his letter (it was George himself who had established these prizes as elector). He then goes on to describe how his ‘little Colony’ is getting on, and proudly relates some of his sons’ academic achievements, dwelling particularly on those of Adolphus and Augustus. Notably, George pays particular attention to the progress that his sons are making in the fields of History, Geography, Moral Philosophy, Mathematics and Experimental Philosophy — categories that resonated strongly with his own notes on the education of princes.

GEO/ADD/2/21. For a high-resolution image of the whole document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here. For a transcription, click here

While unrelated to the financial accounts of the university, these letters show that George had a strong interest in affairs at Göttingen. While a separate paper in the ‘Essays’ considers the history of Oxford Colleges

(though omitting Blackfriars), George’s interest in the mechanics of universities was restricted to Germany — and he further isolates this interest by making his notes on the institution in German. This approach to using vernacular languages resulted in him not only writing about German affairs in German, but also writing essays on the history of French taxation in French.

As might be expected of a Hanoverian monarch, the importance of visiting and studying in Germany appears in other papers within the ‘Essays’. While George never travelled himself, he identified travelling as an important part of a young man’s education, and along with advocating trips to the expected sites in Italy, recommended visits to the German court. The essay “On Travelling” (GEO/ADD/32/1734) explores the benefit to young minds that results from learning languages and developing an understanding of a culture by experiencing it directly.

The medal designed by Edmund Burch discussed in the letter to mark the award of the essay prize at Gottingen