10. A Man of the Arts

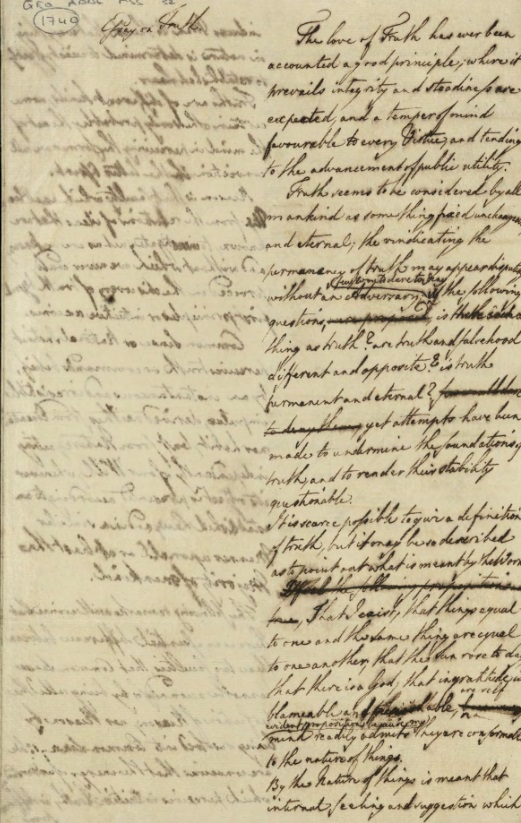

GEO/ADD/32/1740, ‘Essay on Truth‘ [1778-1805]

Source text: James Beattie, An Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, in Opposition to Sophistry and Scepticism (Edinburgh and London, 1771); copy in the Royal Library is of the 1778 edition (RCIN 1050076. WL 82). The text comes from Part 1, ‘Of the standard of truth’ pp. 25-6, Chapter 1 ‘On the perception of truth in general’ pp. 27-9, 37, 40-3 (see the transcript for more details).

For high resolution images of whole document click on image; for catalogue entry, click here; for transcription and indications of relation to Beattie’s text, here

Throughout the ‘Essays’, George can be seen engaging with texts written by prominent contemporary thinkers. This included engaging with works by Scottish Enlightenment thinkers including David Hume, James Beattie and Adam Ferguson. He also reads treatises on art, makes notes on Handel’s compositions and from the Bible, while writing lists of books he wants to purchase, from the works of Henry Fielding and Samuel Foote to architectural texts and volumes on Italian theatre.

The ‘Essay on Truth’ relates to James Beattie (1735-1803)’s An Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, first published in 1771. The paper is a draft, presumably written as an aide memoire as George worked through his own conceptions of the nature of truth. Tellingly, his religious beliefs come to the fore once again as he cites the fact of his existence, the rising of the Sun, and the existence of God as things that demonstrate the fundamental essence of truthfulness.

Over the course of the essay, George turns to consider the importance of reason and common sense, acknowledging the importance of having ‘known unknowns’ to drive the progression of knowledge. This enquiry into human nature is a common concern within the essays, and runs across the notes on art, as well as the constitutional papers where George draws from Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu’s work De l’esprit des loix, as the king is seen reconciling his scientific understanding of the world with his theological and religious views.

To look at George’s views on the arts see:

“Remarks on the Preface to the Account of the Musical Performance in Commemoration of Handel”

“Notes on Reading Harris’s Treatise on Art”

11. America is Lost!

GEO/ADD/32/2010-2011, Essay on America and future colonial policy [?1784]

Source text: Arthur Young, untitled opening essay to Annals of Agriculture and other useful arts, vol. 1 (London, 1784), text from pp. 11, 12-14. (see the transcript for more details).

To read the full essay drafts, click on the image for a high resolution reproduction. For the catalogue entry click here; for a transcription annotated to indicate George’s interactions with his source, click here.

One of the most fascinating, and perplexing, items in the ‘Essays’ are the papers referred to as ‘America is Lost!’ Addressing the American Revolution, the essay is a key example of the ways in which an understanding of the essays can shape, and realign, our understanding of George III as a man and a monarch.

George III followed developments in the colonies closely, and there is no question that their loss was a clear blow — not least as it disrupted the stability of his government. However, in ‘America is Lost!’ we find an alternative perspective on the American Revolution. The essay is neither an original composition nor an instance of copying, rather it is a ‘near verbatim’ extract taken from Arthur Young’s Annals of Agriculture (1784) and replicates content from pages 11-19. While the essay could be a copy of an earlier draft (George III corresponded with Young and even wrote for the Annals himself under the pseudonym of Ralph Robinson) it was most probably commonplaced and reworked by the King as he reconciled himself to the loss of American territories.

The differences between the ‘essay’ and Young’s published text result in a more optimistic view of the consequences for Britain’s future as George reconciles himself to the turn of events. George removes the statistics that Young takes great pains to provide and omits any statements that speculate on economic matters. These amendments and omission change the tone of various passages within the essay. Where Young is tentative, George is more assertive, removing tentative structures such as ‘let us consider’ or ‘is probably the case’, giving a different sense of the ‘brave new world’ that was emerging in the latter stages of the eighteenth century.

For more on this essay, see:

Blog by Dr. Angel-Luke O’Donnell, ‘America is Lost’: https://georgianpapersprogramme.com/2017/01/23/america-is-lost/

Justin B. Clement, “America Lost? The Birth of Britain’s Capitalist Empire” https://georgianpapersprogramme.com/2017/01/20/america-lost-birth-britains-capitalist-empire-2/

To see other examples of commonplacing see:

“Extracts from ye Bystander”

“Letters from Ralph Robinson to “Annals of Agriculture and Other Useful Arts”

12. When is an essay not an essay?

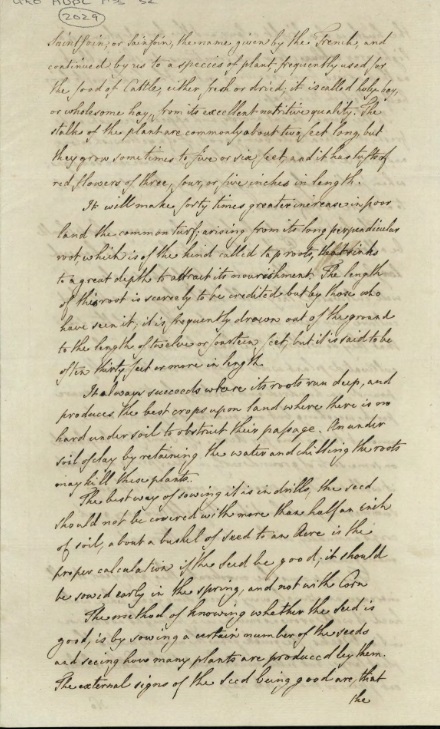

GEO/ADD/32/2029-2030 Notes on sainfoin [1756-1805]

Source text: for 2029: The Complete Farmer: or, a General Dictionary of Husbandry in all its branches sub. ‘Saintfoin’, pp. 382-4. This volume is held in the Royal Collection (ref RCIN 1057470. WL 90) For the details, see transcription.

For 2030: appears to be drawn from The Improved Culture of Three Principal Grasses, Lucerne, Sainfoin, and Burnet (London 1775), pp. 203-14. This volume is held in the Royal Collection (ref RCIN 1057372a). Again see transcription.

For a high-resolution copy of the whole document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here. For a transcript, click here.

George III’s sustained interest in matters of agriculture is a well-established fact. His interest in land management prompted much ridicule at the time, particularly at the hands of the caricaturist James Gillray, who termed him ‘Farmer George’. Yet his interest in agriculture, husbandry, and land management reflect the way in which he viewed his responsibilities as a King and his duty to help ensure the prosperity and proper management of his nation.

In his agricultural writings, George regularly engages with the work of Arthur Young and Jethro Tull, who developed a new method for seed drilling. Good land management skills and an awareness of how to best use the land for trade were essential for his management of the country — something that translates into the education of royalty today, with Prince William having undertaken studies in land economy and management in preparation for his inheritance of the Duchy of Cornwall estates.

The papers on sainfoin, however, while typical of George’s interests in agriculture, are also problematic and challenge how we think about the ‘Essays’ as a coherent corpus within the context of the Georgian Papers. An exact copy of the notes relating to the best way to plant the crop are found outside the ‘Essays’ in the part of the collection known as the ‘Additional Papers relating to George III and Queen Charlotte.’ Both pieces bear a resemblance to The Improved Culture of Three Principal Grasses, Lucerne, Sainfoin, and Burnet (1775), and appears to offer a condensed version of that text’s instructions for cultivating and harvesting sainfoin. The papers that we refer to as the ‘Essays’ may not be as cohesive, or as self-contained, as it first appears!

For another example of an essay with a potential links to other collections see:

“Copy extract from unknown memoirs” and “Instructions from Frederick, Prince of Wales, to his son George”

13. Notes, notes, notes

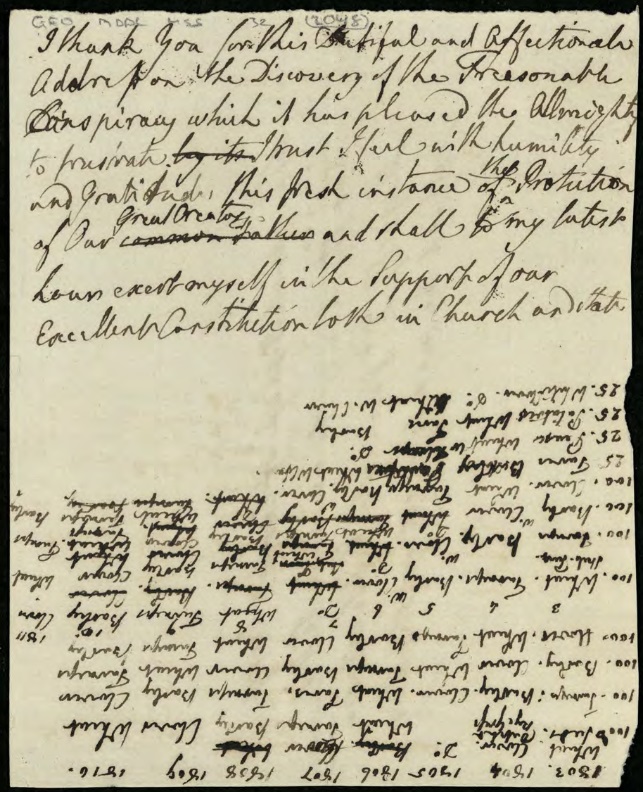

GEO/ADD/32/2048 Memoranda [?1802-1805]

For a high resolution image of the whole document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here. For a transcription, click here.

With papers ranging from mathematical treatises to scientific discoveries, theological matters to history, and geography to music, it is safe to say that George III’s had a broad range of academic interests. For as the King’s collection in the British Library visually demonstrates, he was a prolific collector of books throughout his life and was well versed in a range of topics, concerning himself with affairs of state but also taking pleasure in reading and learning.

That George continually turned his mind from addressing affairs of state to matters of personal interest is demonstrated in a piece of paper that contains: a draft letter, instructions for crop rotation, and a reference to a work that had been lent to him by the Archbishop of Canterbury. While clearly a useful item for understanding the ways in which the King’s mind worked, this fragment is hardly an essay. How these items come to be on the same piece of paper is anyone’s guess, but the fact of their positioning together offers insights into the way George ordered (or didn’t order!) his papers.

The fragmentary nature of this note suggests that the king was turning his hand to a range of affairs in close succession, jotting things down using whichever materials happened to be closest to hand. Yet their appearance on the same sheet of paper means that we can see how George was continually turning between addressing affairs of state and seeking to enhance his own understanding of the world. The draft thank-you note relates to the discovery of the 1802 Despard plot to kill the King. Notably, George here turns to providence and thanks God for his delivery in a subversion of his status as an Enlightened thinker. The notes on crop rotation are for the period 1803-10 and show George engaging with theories for land management that he advocated in his agricultural papers and exchanges with Mr Ducket (GEO/ADD/32/2016) through the medium of Young’s Annals of Agriculture (see above). Decisions relating to planting for 1803 are likely to have made in the autumn/fall of 1802, following the harvest and before the planting season began, and so would need addressing around the time of the Despard plot. Further enhancing this close sequence of events are the Archbishop’s references to the work of Dr Vincent. While it is still unclear which work is being referred to here, it is possible that the book in question is that of William Vincent, the Dean of Westminster and a Classical Scholar, whose The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea first appeared in 1800 and was later dedicated to George III.

While the exact providence of this document is unlikely to be determined, the fact that a single sheet of paper engages with such a range of concerns allows a brief insight into the way George engaged with current affairs. This instance of memoranda may not prove his status as an enlightened monarch, but it goes some way to revealing how George was balancing the demands of state business with his personal interests in agriculture and the arts.

For other memoranda and notes to self see:

“Brief note on the definition of a musical scale”

“Miscellaneous calculations on the army”

END OF THE EXHIBITION

Exhibition credits

Text and selection of documents: Jennifer Buckley

Staging and editing: Arthur Burns

Transcriptions: unless otherwise attributed Arthur Burns and students at William & Mary and King’s College London

Collation of texts in transcriptions: Arthur Burns

Additional background research by: Caitlin Goreing, Kamil Faltynowski, and Daniel Rignall in their digital editions of relevant documents for the module At the Court of King George: Exploring the Royal Archives at King’s College London; Rachel Krier on the relationship of the papers of George III and George IV.

For the Royal Archives: Oliver Walton

Technical development: Sara Belmont and Marie Pellissier (William & Mary)

All visual material courtesy of the Royal Archives and (c) Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II