The Political Day in Georgian London

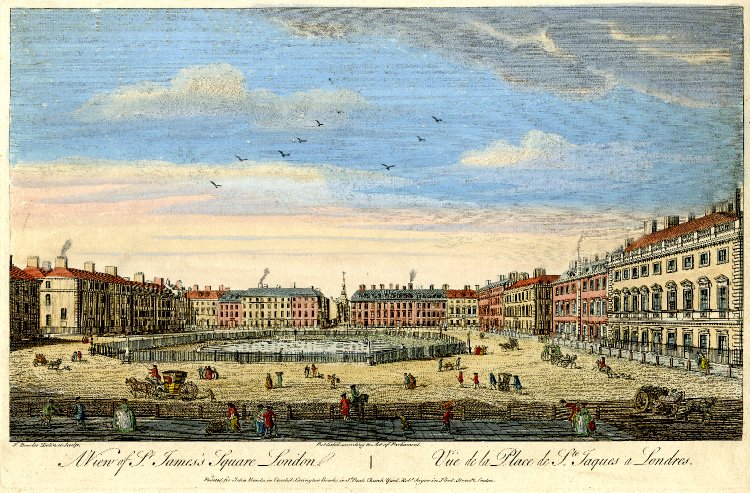

St James’s Square in 1753. Coloured engraving by T Bowles

(Mayson Beaton Collection, English Heritage)

The Political Day in Georgian London: reflections on a lecture by Professor Amanda Vickery (QMUL),

co-hosted by the Centre for Enlightenment Studies and the Georgian Papers Programme

by Angela Lee (MA 18th Century Studies)

Speaking to a packed auditorium on the 23rd of March, Professor Amanda Vickery started her lecture with a gripping account of a group of ladies who stood their ground in an attempt to enter the House of Lords in 1739. They were finally admitted after standing outside for most of the day. For Vickery, this episode was symbolic of female exclusion from politics; the first woman in the House of Lords was only admitted in 1958.

The lecture of the evening was the culmination of ten years of research by herself and Dr. Hannah Greig (University of York). They sought to plot out the schedule of a normal day for the political elite using everyday sources. She peppered her lecture with visual material and anecdotes, which gave the academic lecture a more personal and engaging tone—there were multiple times when everyone erupted into laughter. Her main argument was that women, though excluded from Parliament, were still involved in politics in other ways, since politics in the Georgian era often spilled over into social activities as well.

However, Vickery points out that her project was not simply to write women into politics, but to dispute the idea that aristocratic women were frivolous. She and Greig illustrate that rather than having to split history into high politics and women’s history, the two topics were actually deeply intertwined.

Aristocratic women had the opportunity to own and manage large estates during the eighteenth century, and through these roles, they had power over “rotten boroughs” and appointments. In London, the Parliamentary season took place in the spring and coincided with the social season. Geographically, the day was centered around Westminster and Covent Garden. Often, the day began in a house around the fashionable St. James’s Square, then Parliament, followed by entertainment at the opera or one of the gardens in the evening.

A typical day began at 9 in the morning, which was a normal rising time for both sexes. While Parliament officially opened at 9 (10 in the 1770s), most members arrived around noon and conducted public business around 2 to 3 in the afternoon.

Daily sittings of 6 to 8 hours were common. The morning was reserved for personal matters—letter-writing, shopping, social visits. Men attended levées of the monarch and political ministers, which were used to show patronage and favor. Vickery even noted that during important debates, Parliamentary sittings could go on for days. Members would eat and even sleep in Parliament.

Since Parliament was cramped, urban townhouses, such as the Earl of Shelburne’s Lansdowne House, were also used as political venues. Coffeehouses and chophouses were affiliated with political parties and regularly held political discussions.

The main divide in the day came at dinnertime, sometimes occurring as late as 4 or 5 in the afternoon, and required a change of clothes.

In the evening, social life really took off. London during the eighteenth century offered a multitude of entertainments. Women acted as hostesses for political dinners and parties at their London homes—carefully deciding whom to invite and which parties to attend. Outside of private parties, London offered the opera, theatre, and pleasure gardens (the two most famous being Vauxhall and Ranelagh). Not only entertaining, these were places to see and be seen.

Politically, it was important to observe who mingled with whom. With all these social activities, a bedtime of 4 in the morning was not unusual. As Vickery pointed out, late nights were fashionable because burning candles so many hours after dark was an expensive habit.

The political day of the Georgian era was a largely social affair, spread between across civilian settings and Westminster. London felt like a political “campus”. Illustrating this point, Vickery told the audience that it took 19 minutes for Greig and her to walk at a leisurely pace from St. James’s Square to Parliament. The coffeehouses, chophouses, and shops would have lined the streets in between them. With the mix of activities, husbands and wives could meet during the day, planning routes through the thoroughfares to maximize their socio-political benefits.

Women were able to influence politics through the myriad social activities that were integral to a successful political career. After all, the political day did not end with the dispersal of Parliament.

Vickery’s lecture led to many questions from the audience, particularly on the topic of female sociability. Many commented on how tiring a political day would have been during the eighteenth century. She noted that indeed, a lack of social stamina would have been detrimental for social and political success.

It sounds peculiar, but eighteenth century politicians had to mix both public and private aspects of their lives just in order to be politicians. Political prestige went hand-in-hand with social prestige. Aristocratic women––leaders in high taste and high fashion––had a much larger role high politics than historians had previously given them credit for.

Angela completed her first degree at the University of Chicago in the department of History. This year she is studying at King’s on the MA in Eighteenth Century Studies, an interdisciplinary programme taught in partnership with the British Museum and convened by Dr Elizabeth Eger in the English department. The MA aims to bring together the study of material and intellectual, cultural and political history and draws upon the extraordinary wealth of eighteenth-century resources in London’s museums and archives. The intellectual energy generated through teaching the MA formed a significant factor in founding the AHRI-funded Centre for Enlightenment Studies at King’s.

This blog post was originally posted on the King’s College London English Department blog, on 1 June 2016: https://blogs.kcl.ac.uk/english/2016/06/01/the-political-day-in-georgian-london/