George III’s Papers and acquisition of his ‘Geographical Atlas’

Peter Barber is a Visiting Professor in association with the Georgian Papers Programme, King’s College London.

George III’s geographical collections, now split between the British Library and the Royal Library in Windsor, with small fragments elsewhere, have been almost entirely overlooked by his many biographers. Yet we know that this large collection of about 50,000 maps, charts and views – many originally loose, others in volumes – was something he was passionate about: more so perhaps than his better known collections, where he left acquisitions to ‘experts’.

The so-called ‘Red-Lined Map’ : the revised (1775) edition of the Mitchell map of North America (1755) annotated with lines to illustrate interpretations of previous treaties, used by the British delegation in Paris 1782-3 when negotiating the independence of the USA (detail) (By permission of the British Library Board)

There are items in his geographical collection – ranging from state papers to personal material that only he could have secured. We also know that he chose to place the maps and views in the room immediately next to his bedroom in the Queen’s House (the predecessor of Buckingham Palace) and that he personally consulted it . The collection was part private hobby, part an element of the royal gloire : extensive self-assembled ‘atlases’ of this kind had been fashionable in royal, aristocratic and antiquarian circles since at least the 1680s. Each of these ’atlases’ had their individual characteristics, and George’s was no exception.

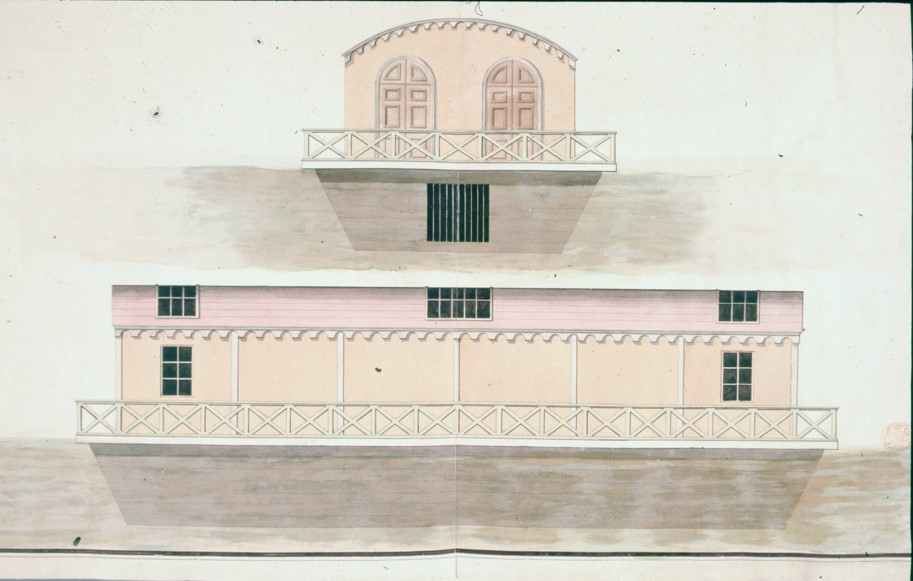

Elevation of George III’s bathing machine at Weymouth, ca. 1792

(By permission of the British Library Board)

George adopted the structure of the collection from his uncle, William, Duke of Cumberland, whose maps he inherited.

![Portrait of William, Duke of Cumberland from John Elphinstone, Drawings of the Castle of Glammis, c. 1747. Frontispiece [By permission of the British Library Board]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Barber-blog-_3.jpg)

Portrait of William, Duke of Cumberland from John Elphinstone, Drawings of the Castle of Glammis, c. 1747. Frontispiece (By permission of the British Library Board)

Like Cumberland, he was interested in military affairs and like his uncle used his position as Commander-in-Chief to acquire military maps of all sorts: fortification, encampment and battle plans with plans for barracks and the sort of topographical maps that were essential for military purposes.

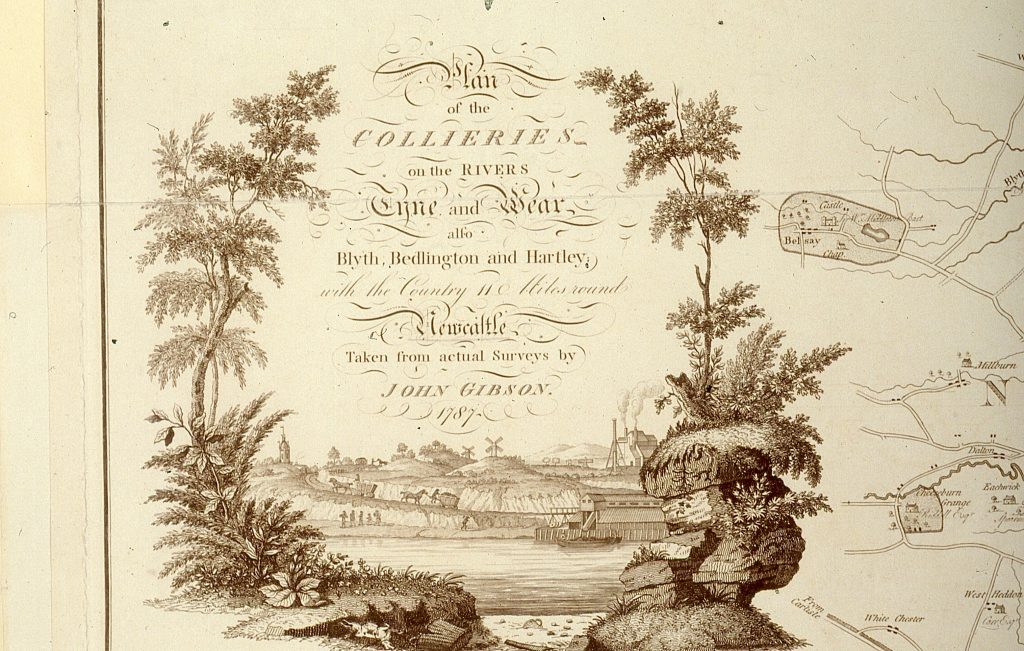

John Gibson, Plan of the Collieries on the Rivers Tyne and Wear, also Blyth, Bedlington, and Hartley, with the Country eleven Miles round Newcastle; taken from actual surveys by John Gibson, 1787. (By permission of the British Library Board)

He also acquired material in areas that personally interested him but which were also useful for government such as canals, communications, agriculture, industry.

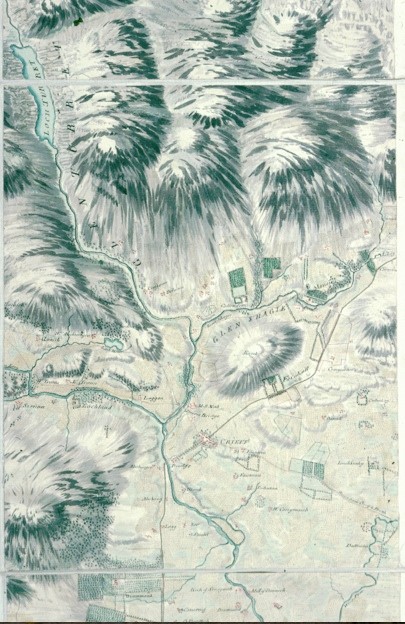

William Roy, Crieff from the Fair Copy of the Survey of Scotland., 1747-55, Draughtsman, Paul Sandby

By permission of the British Library Board

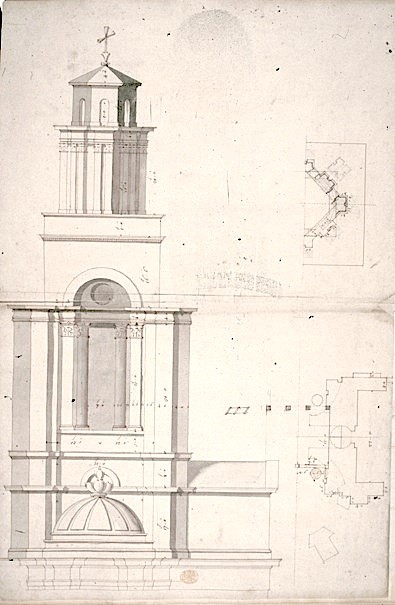

Side-by-side with this went his personal enthusiasms. The collection is filled with architectural plans – including one of the largest collections of plans and elevations by Nicholas Hawksmoor –

Nicholas Hawksmoor, St Anne’s Limehouse,

(By permission of the British Library Board)

and drawings of British (Gothic) antiquity, not surprisingly from the man who was himself an architect manqué (there are plans by him in the collection) and who had a now-vanished Gothick palace constructed in Kew Gardens.

The ‘Geographical Atlas’ served several purposes. One of the most important was as an aid to government, and particularly, in line with his views on the role of an enlightened monarch in a constitutional state, as a source of information independent from that provided by his ministers. Secondly, it was a source of information about the world at large. Its foci reflected the values of his age, as well as the availability of printed and manuscript material. Over and above the British Isles which constitute about 40% of the collection, there is much (in descending order) Italian, French, Netherlandish and German material – the latter largely accounted for my the maps and views of his Hanoverian lands.

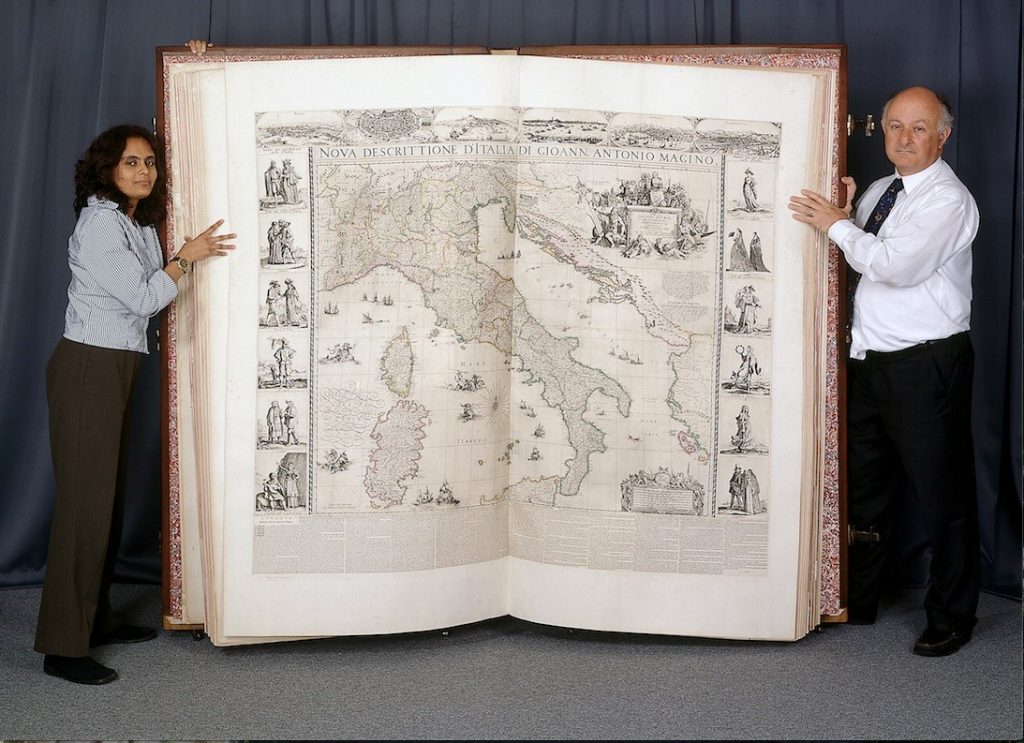

We know only the broad lines of how he acquired this collection. Much, including the largest antiquarian atlas in the world dating from 1660,

The Klencke Atlas assembled in 1660 is the largest antiquarian atlas in the world. The item was presented to Charles II on his restoration to the British throne in 1660.

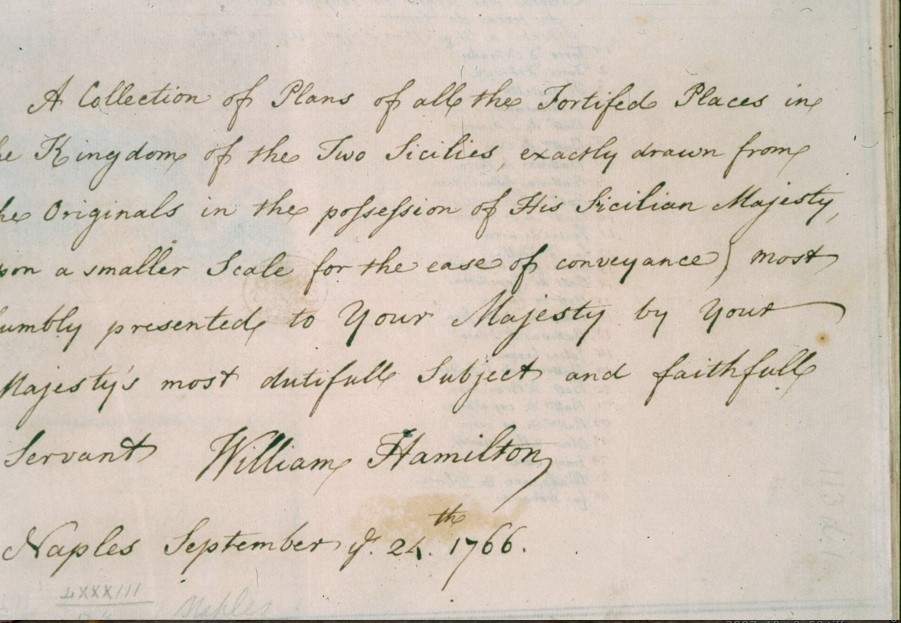

was inherited from his ancestors and predecessors going back to 1660. As with his library, the items George acquired were paid for from his Privy Purse account – and they are missing between 1772 to 1811: the very years when he was most active in building up the collection. This has meant that researchers have had to rely on a close study of the items themselves to discover provenance for this core period. There is the occasional autograph dedication to the King, and in other cases contemporary diaries or letters can help. There is one surviving receipt. There are sometimes endorsements indicating specific sales and lots (though sometimes these refer to sales prior to the King’s actual acquisition of the material, a good example being the Hawksmoor material, where the endorsements refer to the 1737 auction that took place on the architect’s death).

Autograph dedication to George III by Sir William Hamilton, then British minister in Naples, of a manuscript fortification atlas, 1766

George III’s papers could help to fill some of the many gaps in the records and unlock some of the remaining puzzles. Material hitherto regarded as insignificant and ephemeral may prove to be goldmines. To have them accessible on one’s own laptop when one is in easy reach of related material will be an amazing boon. They may help to modify old stereotypes such as the canard accepted without question until recently by those unaware of the Geographical Collections that George was intellectually uninterested and lacked interest in or curiosity about the world beyond Windsor and Weymouth.

By Peter Barber