Digitising Monarchy: Mapping Victoria and Future Prospects

Lee Butcher is an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award PhD candidate with King’s College London and English Heritage.

I am a historian and political geographer. I am undertaking PhD research on behalf of King’s College London and English Heritage exploring the spatial and political practices of the Victorian monarchy, focusing on the royal residence of Osborne House as a case study. I am interested in exploring the ways in which the monarchy’s spatial practices can be examined as a means to highlight the development of the institution’s political and cultural roles. By spatial practices I mean the processes by which ‘royal places’, such as royal residences, were made by the monarchy, and how the institution constructed ‘royal space’, i.e. how their spatial patterns (where they travelled to and from) changed over time.

A central source for this research has been Queen Victoria’s journals, digitised and made available online in 2012. A technological ancestor of the current Georgian Papers Programme, Victoria’s journals provides the digital historian with an unparalleled resource to explore this critical period in Britain’s political history. The digitisation of these 24,805 journal entries not only facilitates convenient access for researchers to this invaluable resource, it makes possible the kinds of digital and quantitative research that historians in the 21st century are increasingly endeavouring to undertake.

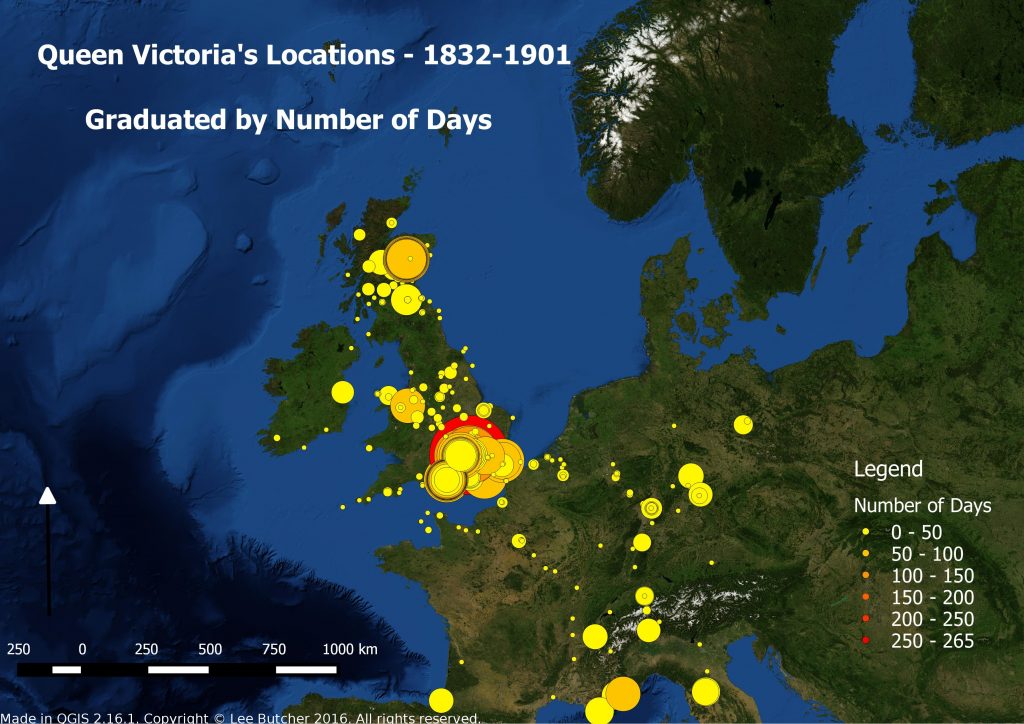

For my own part, naturally for a geographer, I have been keen to map the data present in the journal. With each entry usefully attributed with the name of the location of writing, I have been able to construct a database of the Queen’s whereabouts, showing where she was for each entry in the journal. Recorded by time, as well as place, it has been possible to map (using Geographical Information System (GIS) software) how the Queen’s spatial practices developed from the first entry in August 1832 until the last in January 1901. It has enabled me to produce statistical analysis of the changing patterns of royal visitations to the principal residences (Osborne, Windsor, Balmoral and Buckingham Place), and thus to explore the changing role of each residence over the course of Victoria’s reign. Such an endeavour would have been logistically challenging, and prohibitively time consuming, using either the manuscript copies held at Windsor, or the previously published selections. Improving access to sources, particularly in digital and online formats, allows researchers to be inventive and enables them to undertake complex research projects more efficiently.

The Georgian Papers Programme is an exciting extension of the agenda first articulated by the digitisation of Victoria’s journal. It promises to make readily available a wealth of sources previously accessible only to those researchers with the time and the resources to be able to visit Windsor. The commitment of the Royal Archives to improve access to their vast range of sources is highly commendable. For historians of the monarchy it promises exciting new possibilities for formulating new and inventive research agendas. For historians like myself, whose interests lay in the digital analysis of historical sources, projects such as this can only be good news. The rapid development of digital technology since the completion of Victoria’s journal suggests that the Georgian Papers Programme will provide more advanced tools for researchers seeking to engage with this material, compared to its predecessor, and will undoubtedly prompt a renewed interest in this critical period for Britain’s monarchy. I for one cannot wait to see what the project comes up with, and I cannot wait to get stuck into, and do some mapping of, the resources they produce.