Garter Day in the Archives

Today, Georgian Papers Programme fellow Rachel Banke writes about her experience while conducting research in the archives. Applications for the next round of GPP fellowships are due February 20, 2017. Scholars at all levels—graduate students, junior and senior faculty, and independent scholars of all ages—are eligible for the award. Apply here.

by Rachel Banke

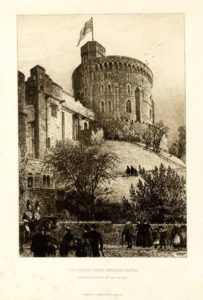

Have you ever eaten a cake decorated like Henry VIII? Well, I have. To be sure, a rotund and comical Henry VIII cake does not grace the Royal Archives every day, but I was graciously treated to a slice when the archives staff hosted me as their guest for Garter Day. How exactly does one celebrate Garter Day besides drinking tea and eating cake? Standing on the battlements of the Round Tower—in the rain, of course—we watched the members of the Most Noble Order of the Garter descend to St George’s Chapel after their formal knighting in the royal residence.

Have you ever eaten a cake decorated like Henry VIII? Well, I have. To be sure, a rotund and comical Henry VIII cake does not grace the Royal Archives every day, but I was graciously treated to a slice when the archives staff hosted me as their guest for Garter Day. How exactly does one celebrate Garter Day besides drinking tea and eating cake? Standing on the battlements of the Round Tower—in the rain, of course—we watched the members of the Most Noble Order of the Garter descend to St George’s Chapel after their formal knighting in the royal residence.

Getting to experience Garter Day at Windsor was especially interesting to me because I study one of the Order’s former members. My research centers on the 3rd Earl of Bute, who was tutor, advisor, friend, and prime minister to George III. My project, “Bute’s Empire: Reform, Reaction, and the Roots of Imperial Crisis,” uses the figure of the Earl of Bute to unpack dynamics of imperial governance and popular political culture on the eve of the American Revolution.

I was especially thrilled to find the Royal Archives holds an immense collection (over 2,000 documents) of George III’s notes and essays spanning from his childhood to near the end of his life. This material provides fantastic insights into key parts of his political philosophy, including topics such as English history, political economy, the system of British government, and the levying of taxes. The chicken scratch of George’s drafts and notes were some of the most interesting pieces because they show how George refined and developed his thought in a collection mostly devoid of dates. The problems of dating most of the material did raise questions for me about how I can use these otherwise rich sources to speak to George III’s thinking during a particular point in his life. However, I was particularly excited to find the Earl of Bute’s comments and corrections on some of these papers.

I also spent a significant portion of my time on family correspondence. Many of these materials fleshed out the full person of George III in funny, surprising, and touching ways. In particular, an affectionate letter from Prince Frederick to his son, the young Prince George, stands out. The letter outlined the humble, principled, and brave way a King needed to approach his duties to his country and people, sentiments which George III took to heart as he ascended the throne intent on removing corrupt influences and producing a reformation of government.

I would like to express my greatest gratitude toward the staff of the Royal Archives and the Omohundro Institute for making this research possible. I would also like to give my thanks to the staffs of the Royal Library, who patiently hosted me during renovations to the Round Tower, and the Royal Print Room, who were exceedingly helpful when I visited to see items in the satirical print and Cumberland maps collections. I eagerly await the launch of the digitization project, which promises to breathe new life into not only our understanding of high political history of the era, but also important aspects of eighteenth-century cultural and intellectual history as well.