The American Revolution in King’s College London’s "Revolution!" exhibition

By Heather Anderson, Special Collections Assistant in the Foyle Special Collections Library at King’s College London and exhibition co-curator

The Revolution! exhibition runs until Saturday 20 May 2017 in the Weston Room of the Maughan Library at King’s College London.

To mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution, King’s College London’s Foyle Special Collections Library is holding an exhibition in the Weston Room of the Maughan Library on the theme of revolution. Further details are available here: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/library/archivespec/exhibitions/maughan.aspx

The exhibition draws on the unique and distinctive holdings of the Foyle Special Collections Library, including the historical library collection of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to explore events of 1917 which led to the rise of the Soviet Union, and to explore the concept of revolution more broadly.

The exhibition covers several significant political revolutions of modern times, including the American Revolution of the late 18th century. This post will focus on two items currently on display relating to the American Revolutionary War.

(1) Extract from The Boston evening-post, of September 2, 1765. [Sl: sn, 1765]

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Historical Collection FOL. HF3025 GRE

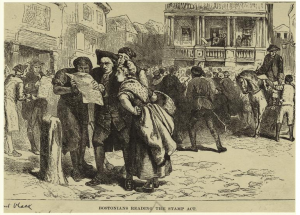

The American Revolutionary War arose from tensions that had been building between colonists and the British authorities for more than a decade. Prior to the outbreak of the war in 1775, colonists had protested against taxes imposed by the British government, arguing that only their representative assemblies could tax them. One such act imposed was the Stamp Act, a tax on all printed documents in the American colonies introduced in 1765. Objectors to the tax resorted to mob violence in opposition, aiming to intimidate stamp collectors into resigning. The Extract from The Boston evening-post, of September 2, 1765, held in the Foyle Special Collections Library and currently on display as part of the Revolution! exhibition, contains extracts from proclamations and letters on the subject of riots occasioned by the imposition of the Stamp Act.

Bostonians reading Stamp Act, 1765. By New York Public Library. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Political violence and protest

In one proclamation the governor of colonial Massachusetts, Francis Bernard (1712-79) reports riotous scenes that occurred on 26 August 1765 in Boston. Bernard reports how mobs attacked and pillaged the properties of several political figures of the province in opposition to the Stamp Act. The most brutal attack described is that against the property of Thomas Hutchinson, lieutenant governor of Massachusetts. Bernard describes how a mob forcibly entered Hutchinson’s home and destroyed fittings and windows, demolished and stole furniture, clothes and money, and even uncovered part of the roof:

…the said people continuing thus riotously and tumultuously assembled the whole night and until day-light the next morning, committing divers outrages and enormities and threatening the custom-house, and the houses of divers persons, to the great terror of his majesty’s liege subjects.

Riots and resignations

Similar riots broke out in other colonial towns, resulting in mass resignations of the stamp distributors. This made the Act incredibly difficult to implement, and led to its repeal just one year after it had been sanctioned. The issues of taxation and representation raised by the Act put a strain on the relationship between Britain and the colonies, with relations further deteriorating over the next decade until the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775.

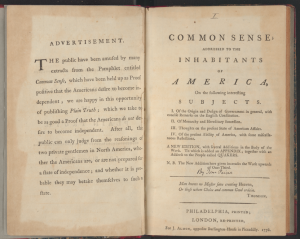

(2) Thomas Paine. Common sense. Philadelphia, printed; London: re-printed, for J Almon, opposite Burlington-House in Piccadilly, 1776

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Historical Collection E211 PAI

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in April 1775, the majority of colonists who took up arms against British soldiers did not desire independence. Colonial leaders hoped eventually to resolve the issues that had led to growing tensions between Americans and the British authorities, such as taxation without representation and the presence of the British army in the colonies. However, over the course of 1775-76 the independence movement grew substantially. This was partly due to the immense popularity of Thomas Paine’s pro-independence pamphlet Common sense.

Widespread circulation

Common sense was the most widely circulated pamphlet published during the American Revolutionary War. Within three months of its publication in 1776 it was claimed that 120,000 copies had been sold and second editions of the work were published within weeks. In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry on Paine’s life, it is recorded that Benjamin Rush, an associate of Paine and one of the United States’ Founding Fathers, recalled in July 1776:

Its effects were sudden and extensive upon the American mind. It was read by public men, repeated in clubs, spouted in schools, and in one instance, delivered from the pulpit instead of a sermon by a clergyman in Connecticut.

The pamphlet made the case for independence for the American colonies, arguing in favour of a democratic republican government. Paine argued that ‘government by kings runs contrary to the natural equality of man’ and that Americans should regard England as a ‘tyrannical oppressor’.

The text and seditious libel

The text’s accessible prose style and impassioned arguments garnered enthusiasm for the cause of independence, and even those opposed to Paine’s arguments were inspired by his devotion to the cause. The edition of Common sense held in the Foyle Special Collections Library, and currently on display as part of the Revolution! exhibition, is a first English edition of the pamphlet, reprinted from the original American edition in 1776. This copy has hiatuses (omitted words and phrases) throughout the text. It is believed that the printer omitted the most controversial parts of the text, which included personal attacks on George III, to avoid accusations of seditious libel. The hiatuses in this copy have been filled in with pen and ink, possibly by clerks employed by the printer to do so. This technique would have given readers access to the text’s seditious ideas, whilst protecting the printer from prosecution.

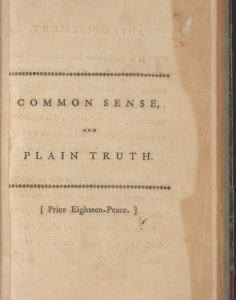

Plain truth

This edition is published with James Chalmers’ critical essay Plain truth, which was written in opposition to Paine’s arguments. There is a half-title page at the beginning of the work introducing both Common sense and Plain truth, but each work has a separate title page, albeit with the same imprint statement.

The advertisement in this edition states how Common sense has been ‘held up as proof positive that the Americans desire to become independent’ and that the publisher is ‘happy in this opportunity of publishing Plain truth; which we take to be as good a proof that the Americans do not desire to become independent’.

The Revolution! exhibition runs until Saturday 20 May 2017 in the Weston Room of the Maughan Library at King’s College London. It is open to the public Monday – Friday 09.30-17.00 and Saturday 10.00-18.00.

Bibliography

Mark Philp, ‘Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21133, accessed 28 March 2017]