Introducing the Georgian Goodies Series

Marie Pellissier is a Digital Projects Apprentice at the Omohundro Institute. She is a first-year PhD student at William & Mary, and works on Early American women’s intellectual history.

This is the first in a series of blog posts called Georgian Goodies, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme! Follow #GeorgianGoodies on Twitter at for new blogs and extras.

October was a momentous month for the first three Hanoverian kings. George I was crowned on October 20, 1715. George II was crowned on October 11, 1727. And, on October 25, 1760, George III ascended to the throne on the death of his grandfather.

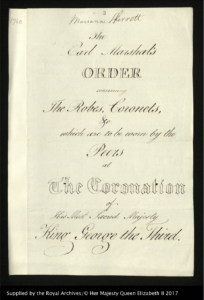

The Earl Marshal’s Order concerning the Robes, Coronets, &c. for the Coronation of George III

George III’s coronation took place on September 22, 1761, two weeks after his marriage to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. This week’s Georgian Goodie is a document from his coronation: The Earl Marshal’s order concerning robes to be worn by the peers at the coronation ceremony. To see the full document, click here.

The Earl Marshal is a hereditary royal office. In the fourteenth century, the Earl Marshal was responsible for the monarch’s stables as well as marshalling troops in times of war. By the end of the Middle Ages, the office had evolved to include responsibility for planning all major royal ceremonies, including coronations and funerals. In 1672, Charles II formally attached the office to the Dukedom of Norfolk, and the Dukes of Norfolk have held the office ever since.

Earl Marshal at the coronation of George III was Edward Howard, the 9th Duke of Norfolk. Coronations of British monarchs were meticulously planned affairs, down to the last details of clothing. British peers were expected to wear robes “of Crimson Velvet edged with Miniver pure.” Miniver is a pure white fur from the belly of the stoat. Peers wore miniver fur as a cape over their shoulders, with rows of ermine–or the black tails of the stoat–on the cape which indicated their rank. Barons were to wear two rows; viscounts, two and a half; earls three; marquesses, three and a half; and dukes, four.

Beneath the robes, the peers were ordered to wear “habits of very rich Gold or Silver brocade” and “Swords in Scabbards of Crimson Velvet.” No detail was too small; even their hairstyles were dictated by the Earl Marshal. “Either…full-bottomed Peri-Wigs or Wigs without Bags tied behind with a Ribbon curled and flowing down to the small of the back.” Periwigs were popularized by Louis XIV in the seventeenth century, and were high, flowing masses of curls. By the eighteenth century, wig styles had changed, and smaller, less elaborate wigs were often tied in ponytails (in modern parlance) and the ponytails tucked into silk bags, as in this 1762 portrait of George III. Peers also wore coronets of “Silver Gilt” with “no jewels or precious stones.”

Coronations formally present the sovereign to the people and to God. Clothing at a coronation indicated status and position, and, like all the other parts of this traditional, heavily scripted ceremony, contributed to the legitimization of the monarch. The monarch’s own coronation robes were the most sumptuous of all. The form of the coronation of British monarchs has been largely unchanged for centuries, and monarchs depend on the records of previous coronations to help plan their own.

Louis XIV of France, 1701, by Hyacinthe Rigaud. Louis sports a periwig with long, flowing curls. |

George III, by Allan Ramsay, 1762. In this portrait, George III wears a wig with a silk bag over the ponytail. |

George III in Coronation Robes, by Allan Ramsay, c. 1761-1762. George III’s cloak is trimmed with ermine. |

Marianne Skerrett, Head Dresser and Wardrobe-Woman to Queen Victoria, c. 1859. Photo courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Curiously, at the top of the front page of this document from George III’s coronation is the name Marianne Skerrett.

Skerrett was the Head Dresser and Wardrobe-Woman to Queen Victoria, and began working for the Queen upon her accession to the throne in 1837. Skerrett was responsible for managing Queen Victoria’s wardrobe, including handling bills and interactions with various tradespeople and ensuring that the Queen’s clothing was kept in good repair. When Skerrett passed away in 1887, Queen Victoria wrote in her journal that Skerrett had also made arrangements with artists on behalf of the Queen, and praised her for her years of loyal service. Skerrett’s position as the Queen’s dresser meant that it was critical for her to be aware of the sartorial regulations for the coronation, which may explain why her name is on this document.”

Coronations are moments of continuity for the monarchy, steeped in tradition and depending heavily on precedent. The Earl Marshal’s order from George III’s coronation, with Marianne Skerrett’s name on it, reminds us of the importance of this tradition, both to George III, and to his successors.

References

“Earl Marshal,” in Stephen Friar, ed., A New Dictionary of Heraldry (Alphabooks Limited, 1987), 131, accessed 9/24/2018), http://www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk/online/content/index1211.htm.

College of Arms, “Planning the Coronation,” 2018, accessed 9/24/2018, https://www.college-of-arms.gov.uk/news-grants/news/item/84-planning-the-coronation.

Philip Mansel, Dressed To Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2005). https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vm74n.1?refreqid=excelsior%3Ab2324a068ad21ad03c884c693735034f&seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents

Royal Collection Trust, “Miss Marianne,” https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/search#/7/collection/2906440/miss-mariann.