Ghosts! In the Archives! We Thought You Ought to Know

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

It’s almost Halloween! We may or may not have found some ghosts in the archives… but we shall leave the final determination about whether or not there are specters in the stacks up to you, dear readers.

King George III and his wife, Queen Charlotte, had fifteen children. George III was an attentive, loving father, and enjoyed having his children around him. He and the Queen were devoted to their children, making sure that they had the best tutors, toys, and healthcare that money could buy.

Prince Octavius, in a 1782 portrait by Thomas Gainsborough

Prince Octavius, born February 23, 1779, and Prince Alfred, born September 22, 1780, were the King and Queen’s eighth and ninth sons, respectively. Prince Alfred died in August 1782, before his second birthday, after a smallpox inoculation weakened his already delicate health. The King and Queen mourned the death of their youngest, and lavished even more affection on Octavius after the death of Alfred.

In the spring of 1783, Octavius, whom all described as a happy, cheerful, and good-natured four-year-old, was taken with his sister Sophia to be inoculated with the same smallpox virus that had killed his brother Alfred. Sophia recovered, but Octavius did not. He died on May 3, 1783.

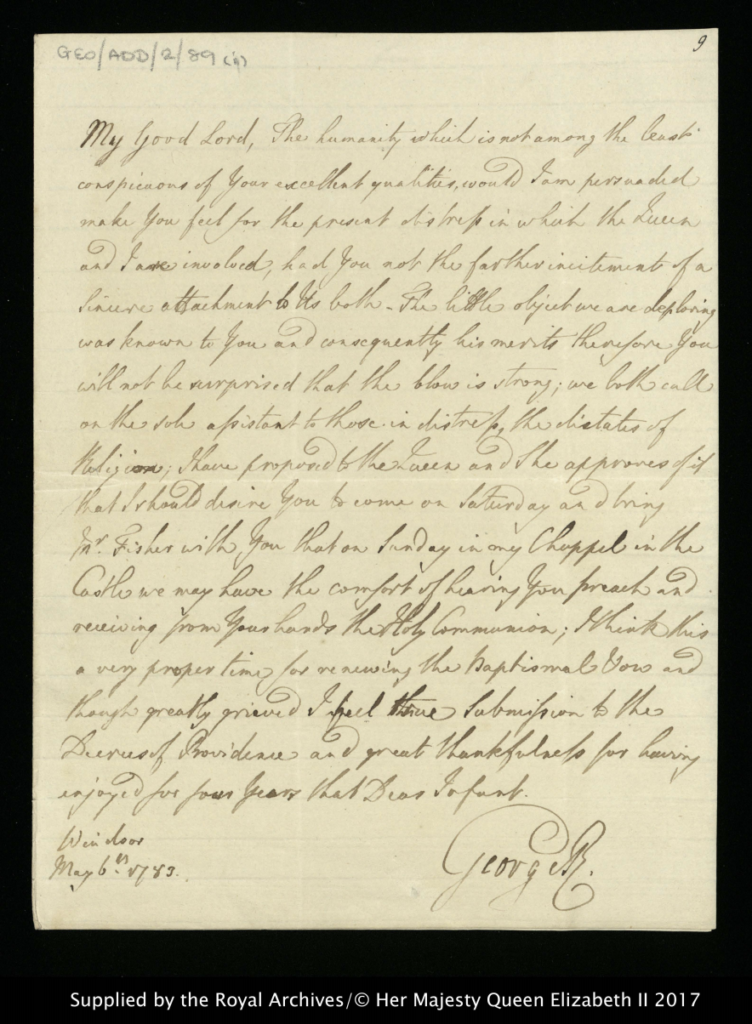

His parents, particularly his father, mourned his loss deeply. Three days after Octavius’s death, on May 6, 1783, George III wrote to the Bishop of Worcester, asking him to lead a private service in Octavius’s memory. “The blow is strong…” the King wrote. “Though greatly grieved, I feel…great thankfulness for having enjoyed for four years that Dear Infant.”

Letter from George III to the Bishop of Worcester after the death of his son, Prince Octavius.

Three months later, George III wrote to General Jacob de Bude, sending him a likeness of Octavius, whose absence the King felt more and more each day. (To learn more about the King’s connection with de Bude, read Jim Ambuske’s blog, “The Admiral and the Aide-de-Camp.”)

Octavius’s presence lingered after his death. The King and Queen continued to grieve for months, and Octavius’s image was included in a family portrait by Thomas Gainsborough completed after his death.

The King dwelt on the death of his two young sons for much of his later life. As George III began to grow ill and exhibit bouts of madness, his son Octavius returned to him. On Christmas Eve 1788, the King was seen rocking and nursing a pillow, which he told observers was his son Octavius, born again.

Ghost or no ghost, the loss of his son haunted the King for years, and reminds us that even for royalty in the eighteenth century, death was ever-present.

References:

Hibbert, Christopher. George III: A Personal History (New York, 1998).

George III to General Jacob de Budé, October 23, 1783. Royal Archives, GEO/ADD/15/0472

https://gpp.rct.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=DEBUDE%2f1%2f16&pos=3.

George III to the Bishop of Worcester, May 7, 1783. Royal Archives, GEO/ADD/2/89

https://gpp.rct.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=ADD2%2f1%2f7&pos=6.

“Princes Octavius and Alfred,” English Monarchs, c. 2018.