Behind the Scenes in the Chapel Royal: The Chapel Royal Memorandum Book

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

What’s so special about the Chapel Royal? That phrase refers not to the building itself, but to the group of people responsible for running religious services for the monarch and their family. The Chapel Royal has been in place in one shape or another since the eleventh century, and continues to the present day. It is responsible for the smooth performance of religious services, a particularly important task given the monarch’s position as Head of the Church of England after the Reformation.

This memorandum book provides insight into the workings of the Chapel Royal under George I, George II, and George III (to see the entire book, click here). It contains a profusion of information about the chapel, including: a list of the officers of the Chapel Royal in 1721 and 1727, and memoranda about the order of services, including Maundy Thursday. It also includes notes from the 1740s about how and when to conduct services around great court events, like balls for Twelfth Night and the monarch’s birthday, as well as minutes of the Annual Chapter meeting (the governing body of the Chapel Royal), and financial accounts through the 1780s.

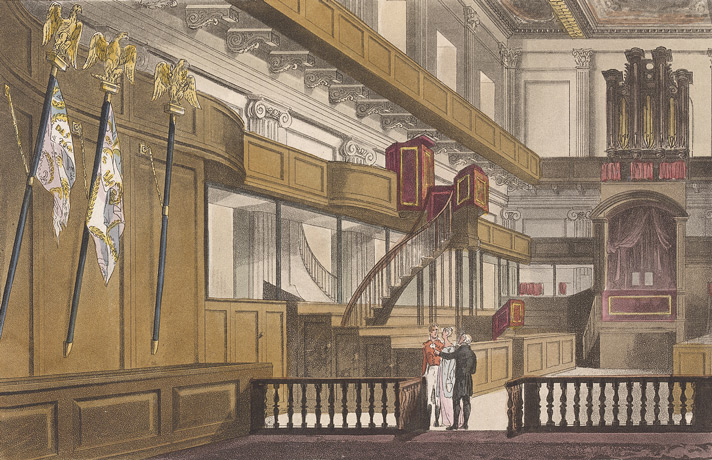

The Chapel Royal at Whitehall, c. 1811. The Chapel Royal at Whitehall was in the former Banqueting House, which was renovated by Sir Christopher Wren after the a 1698 fire. Image courtesy of the British Library.

These administrative details may sound dull, but they provide a glimpse into the workings of royal worship, and, importantly into the people who made it possible. The Chapel Royal required a vast team, from the Sub-Dean in charge of all appointments, to the cleaning women and others who made sure that the day-to-day logistics of the Chapel ran smoothly. The Dean of the Chapel Royal was traditionally a bishop, and in 1721, Edmund, Bishop of Lincoln, was sworn in as Dean of the Chapel Royal under George I. The Dean, however, generally was not responsible for the day-to-day operation of the Chapel Royal; that task fell to the Sub-Dean.

The Reverend Edward Aspinwall, the Sub-Dean of the Chapel Royal in 1721, oversaw two composer/organists and a bevy of “Gentlemen of His Majesty’s Chapel.” Aspinwall also oversaw Dr. William Croft, the Master of the Children, who was responsible for the education as well as the housing of the young boys who were part of the chapel choir. This office, Master of the Children, dates back as far as 1473. Other musicians included Thomas Brooks, the bell ringer, John Shore, the lutanist, Francisco Goodsonce, a violist, and Samuel Clay, the organ blower, whose job was to pump the bellows that provided air to the chapel organ.

The Chapel was also a physical place: at Whitehall, the Chapel was in the former banqueting house, renovated by Sir Christopher Wren into a chapel after a 1698 fire. The foreign chapels–Dutch, French, and German Lutheran–at St. James’s also came under the control of the Dean and Sub-Dean. The Lutheran chapel, was located in a small wooden building that is no longer standing, on the southern side of St. James’s Palace. The Dutch and French chapels, established by William III, met in the Queen’s Chapel, built by Inigo Jones for the Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria in the 1620s. In 1781, the foreign chapels swapped locations: the French chapel moved into the small wooden chapel that the German Lutherans had been using, and the Lutherans used the Queen’s Chapel.

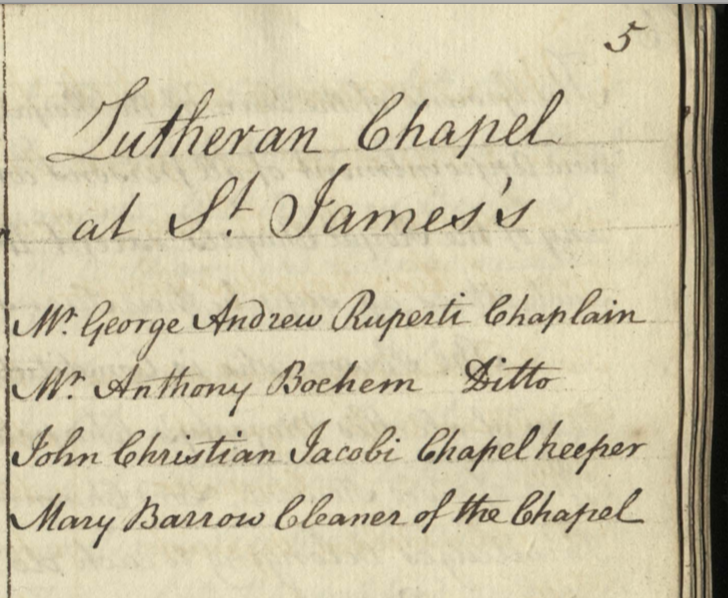

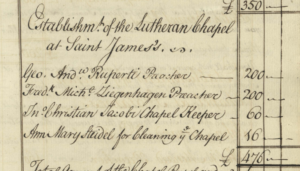

It is easy to focus on the architects who designed the chapels and the preachers and musicians who performed services for the monarchs. But the memorandum book also reminds us that someone had to keep the chapel clean–and that task fell to women. In 1721, a woman named Mary Barrow was listed as the appointed “Cleaner of the Chapel” for the Lutheran establishment at St. James’s. Six years later, in 1727, that position had been given to a woman named Ann Mary Steidel, who received £16 per year for her labors. Certainly compared to the preachers, with an income from the chapel of £200 per year, this was not a lot of money. While calculating average annual income in the early eighteenth century is a remarkably difficult thing to do, historians have estimated that £1 in the 1720s was worth between £200-£300 in 2014. So Ann Mary Steidel’s £16 per year was certainly not enough to make her wealthy, but in an age when approximately 52 percent of families had an income under £25 per year, it was probably enough to live on.

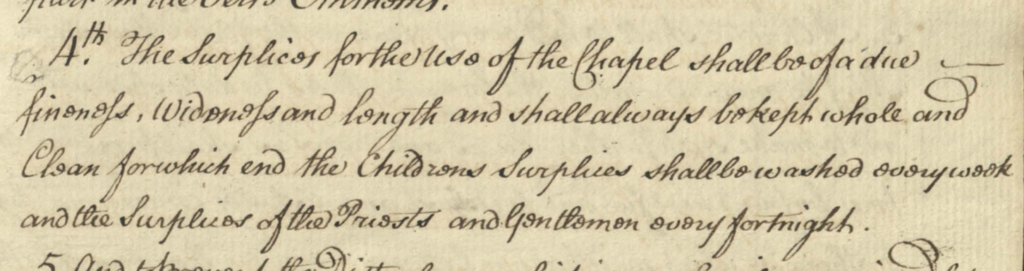

Notably, Ann Mary Steidel and Mary Barrow are the only women listed as part of the chapel’s establishment–all the other positions are filled by men. It is likely, however, that they were not the only two women whose labor helped keep the chapel running. The “Rules for the Decent and Orderly Performance of Divine Service” laid out in this volume required, amongst other things, that “The Surplices [the loose white linen vestment worn over the cassock by members of the Chapel, including the choir]… shall always be kept whole and Clean for which end the Childrens Surplices shall be washed every week and the Surplices of the Priests and Gentlemen every fortnight.”

Item 4 on the list of “Rules for the Decent and Orderly Performance of Divine Service” requires that the children’s laundry be done once a week.

The Memorandum Book does not tell us who did the laundry for the Chapel Royal, or how much they were paid, but it’s likely that they, like the other cleaners, were women. The children of the choir, who lived with the Master of the Children, might have been learning music and singing for the Royal Family, but they were still young (and probably stinky) boys, whose clothes needed to be cleaned frequently!

References