Illuminating the Virtuous King George III

Cassandra Good is an assistant professor of History at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia. She was awarded an Omohundro Institute Georgian Papers Programme fellowship in 2017. Professor Good is currently working on a study of George Washington’s family in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, examining how the next generation shaped the family’s public image and political role in the new nation.

by Cassandra Good, Marymount University

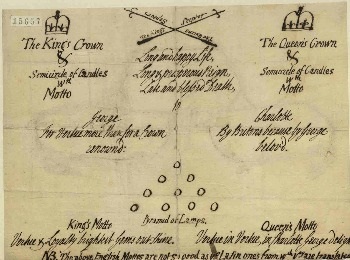

Plan for an illumination in honor of King George III

One of the first documents I saw in my month of research in the Georgian Papers at the Royal Archives was a curious drawing. It was at the top of a box of nearly 700 documents relating to King George III, and it was an unsigned diagram. It was labeled “Plan for Illumination” in the box’s table of contents, and it showed crowns, crossed swords, a series of mottos, and a planned pyramid of lights. I had read about late-eighteenth century illuminations and transparencies, in which candlelight created images on buildings at night, but I had never seen a plan for one.

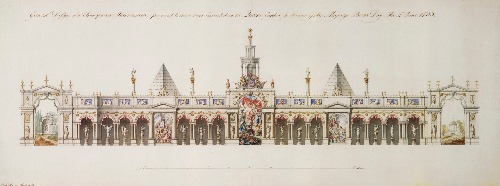

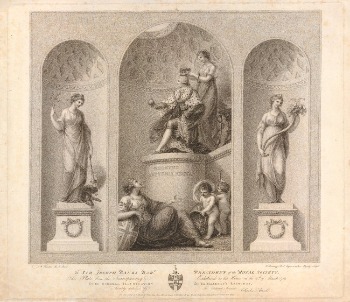

A transparent illumination designed for the King, 1763

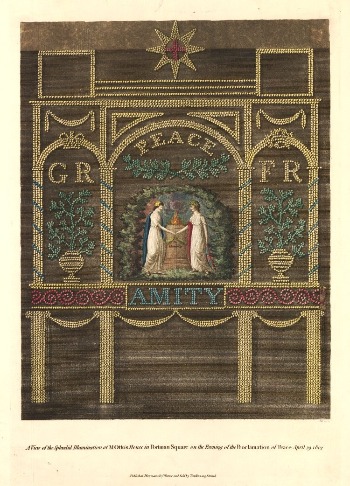

Illuminations were simply candles placed in windows, often in a pattern, to celebrate a patriotic occasion. They were often accompanied by transparencies, or paintings on transparent material that were placed on architectural features of buildings and lit from behind. The Royal Collection contains a drawing of a 1763 design by architect Robert Adam for what he called a “transparent illumination” to celebrate the King’s birthday. This is a far more elaborate design than the plan I had discovered and it relied more on paintings than candles. Perhaps a closer analogue was the decoration of the French Ambassador’s home after the Peace of Amiens in 1802.

An Illumination at M. Otto’s house, 1802

The problem with the diagram I had seen was that there was no sign of when, where, or by whom the illumination had been planned. Was it ever even carried into effect? Who was this admirer of the king who had imbibed George III’s own strenuous efforts at portraying himself as a virtuous father of both his family and the country, the ideal patriot king?

A document near the very bottom of the same voluminous box helped solve the puzzle of the date, setting, and occasion for the illuminations diagrammed. Several pages [16320-1] by the domestic chaplain to Bishop Richard Hurd described the visit of royal family to Worcester and Hartlebury castle in early August 1788. In the midst of a lengthy description, the author described some special decorations placed on his house:

“over my Door…was a large Blue Scroll wth ye following Inscriptn in yellow Letter: Dice feliciter vivant; Dice prospere regnent; [Serv?] beate Morianteu Georgious Charlotta; this Scroll was illuminated by a Pyramid of 10 Lamps; under Georgius was a Smaller Scroll Virtute Coronam ornans, & under Charlotte another Chara Regi Britannis amata. Over ye Garden Gate were black & White Schrolls with Translations of ye Latin ones long & hapily live, long & prosperously reign, late & blessedly Die George whose Virtue ornaments his Crown; Charlotte dear to ye king by Englishmen beloved.”

It’s not a precise match, but this description is remarkably close to the diagram. At the top of the illumination diagram are the words “Long and happy Life, Long & prosperous Reign, Late and blessed Death.” Under George, the illumination reads “For Virtue more than from a Crown renowned,” while under Charlotte, it says “By Britons because by George belov’d.”

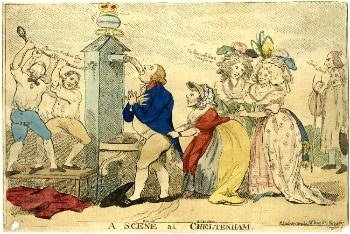

“A Scene at Cheltenham” (cartoon), published 1788

The occasion for the chaplain’s illumination was George III’s recovery from a brief illness in the summer of 1788 after five weeks at Cheltenham. The king, queen, their three eldest daughters, and a small number of courtiers and servants had traveled to the spa town together. With the king’s health considerably improved by the end of July, the royal party travelled to visit George III’s friend Bishop Hurd at Hartlebury and then at the Bishop’s Palace in Worcester. The illuminations were just one part of a celebration with speeches, a procession, and joyous crowds celebrating the king’s recovery.

Illumination for His Majestry’s Recovery, 1790

Unfortunately, George III’s health became even worse that fall and he suffered his first lapse into delirium. But when he recovered and returned to public life in March 1789, he received an even large celebratory reception in London. American ambassador to France Thomas Jefferson, then visiting London, described the illuminations of March 10 (the day Parliament extended official celebratory remarks) as “universal, brilliant and beautiful.”

Such illuminations would have been familiar to Jefferson; Americans had not eschewed this British tradition. There were illuminations celebrating patriotic events in the new country, such as the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia and visits of President George Washington. During Washington’s visit to Savannah in 1791, for instance, one house had candles arranged in the shape of a W.

Washington “Non Vi Virtute Vici” copper, 1786

A particular word used to describe George III would have also had resonance for Americans—virtue. During and after the Revolution, virtue was a constant theme in discussions of what qualities the new republic needed in both its citizens and its leaders. George Washington in particular was an exemplar of virtue. Around the same time as the illumination extolling George III for this quality, Americans could use coins with George Washington’s profile and the phrase Non vi virtute vici, or “I prevailed not by might, but by virtue.” Both the illumination and the coin use Latin to harken back to ancient Rome, an important source for the English Commonwealth philosophy of the late 17th century that influenced both British and American political ideals.

Thus both George III and George Washington won praise in word and image not simply for being leaders, but for their personal character. Their wives, too, were admired public figures, although not necessarily for their own merits. As the illumination design reads, Queen Charlotte was “by Britons because by George beloved,” and similar could be said for Martha Washington.

One decorated page, recording for posterity what would have been a beautiful but ephemeral display, thus illuminates (excuse the pun!) both the world of George III and the closer than expected connections to George Washington. Both Britons and Americans admired the Georges at the heads of their nations for their virtue, lighting the streets of their towns to make their admiration shine.

Image credits:

Plan for an illumination in honor of King George III, artist unknown. Image provided courtesy of the Royal Archives, ref. GEO/MAIN/15657.

“General Design of a Transparent Illumination, proposed to have been Executed in the Queen’s Garden in Honour of His Majesty’s Birthday, The 4th of June 1763” by Robt. Adam, Architect, 1763. Pencil, pen and ink and watercolour. Image provided courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust, copyright HM Queen Elizabeth II.

“A View of the Splendid Illumination at M. Otto’s House in Portman Square on the Evening of the Proclamation of Peace April 29 1802,” by James Ward. Etching and aquatint with hand-colouring. Published by J.F. Tomkins, London, 1802. Image provided courtesy of the British Museum.

“A scene at Cheltenham.” Hand-coloured etching. Published by S.W. Fores, Piccadilly, July 28, 1788. Image provided courtesy of the British Museum.

“Transparency Exhibited…on the General Illumination for his Majesty’s Recovery.” Etching. Published by Charles Ansell, London, 1790. Image provided courtesy of the British Museum.

“Washington `Non Vi Virtute Vici'” copper, 1786. Mint uncertain. Origin New York, New York. Image provided courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation e-museum.