Musical Moments: Handel's "Messiah," Musical Patronage, and Princess Augusta

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

Handel’s oratorio “Messiah” is staple of the Christmas season, and December inevitably brings about performances of this piece. However, George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), the composer, thought of the piece as one for Easter, and indeed, the work became associated with Christmas only in the nineteenth century. Some scholars argue that “Messiah” became associated with Christmas because there are other large choral works, like Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion,” associated with Easter. Nevertheless, “Messiah” was popular from its premiere. After its debut in Dublin on April 13, 1742, it moved to London, where members of the Royal Family attended performances. An unsubstantiated legend holds that King George II was so moved by Handel’s music at the London premiere that he stood for the Hallelujah Chorus–but there is no documentation for this legend, and it is unlikely that the King was in attendance at the premiere, as none of the newspaper accounts mention his presence.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel’s career was built on patronage. As an eleven-year-old prodigy in Germany, his talents were first recognized by the Duke of Weissenfels, who encouraged Handel’s father, a doctor, to allow his son to pursue music. After moving to London in 1710, Handel quickly gained the attention and favor of Queen Anne. After her death in 1714 and the ascension of George I, Handel continued to establish himself as a favored composer amongst the elite. He became a British subject in 1727, which allowed him to be appointed as a composer of the Chapel Royal (for more information on music in the Chapel Royal, click here). With the support of the Royal Family–first George I, then George II and Frederick, Prince of Wales, Handel established himself as the premier composer in London and indeed in Europe.

Prince Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, was interested in a variety of musical entertainments, including opera and oratorios. The oratorio form had originated in Italy around 1600. Soloists, backed by a choir and small orchestra, performed music that narrated a story, often religious in origin. Oratorios, which did not require glamourous sets or expensive foreign performers, were much cheaper to produce than operas. Handel’s oratorios were popular with the British nobility, and Prince Frederick Louis was a frequent attendee.

The Prince of Wales’ attendance at performances of Handel’s work has been much discussed among scholars. Some scholars have argued that because the Prince withdrew his support from Handel’s opera company in 1734, he must have withdrawn his favor from Handel entirely. This, however, is not true; the Prince of Wales continued to attend performances of Handel’s oratorios,

Princess Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, 1754

sometimes with his wife, sometimes without her.

Augusta, Princess of Wales, was 17 when she married the 29-year-old Frederick in 1736. By all accounts, their marriage was not a particularly loving one, and Frederick used Augusta as a tool in his constant combat with his parents. Despite this, they made regular public appearances together, and in April 1739, attended Handel’s oratorio “Israel in Egypt” together–after the Prince had already seen it once on his own. For this privilege, the Prince paid Handel £10.10s for each performance that he attended.

£10.10s was the going rate for the Prince and Princess’s attendance at Handel’s oratorios. Each time they attended, they paid Handel–almost always after the fact. And while the Prince’s patronage of Handel ended when the Prince died in 1751, the Princess of Wales continued to enjoy his music. She did not go out in public very often after her husband’s death, but on occasion, continued to attend performances of Handel’s work.

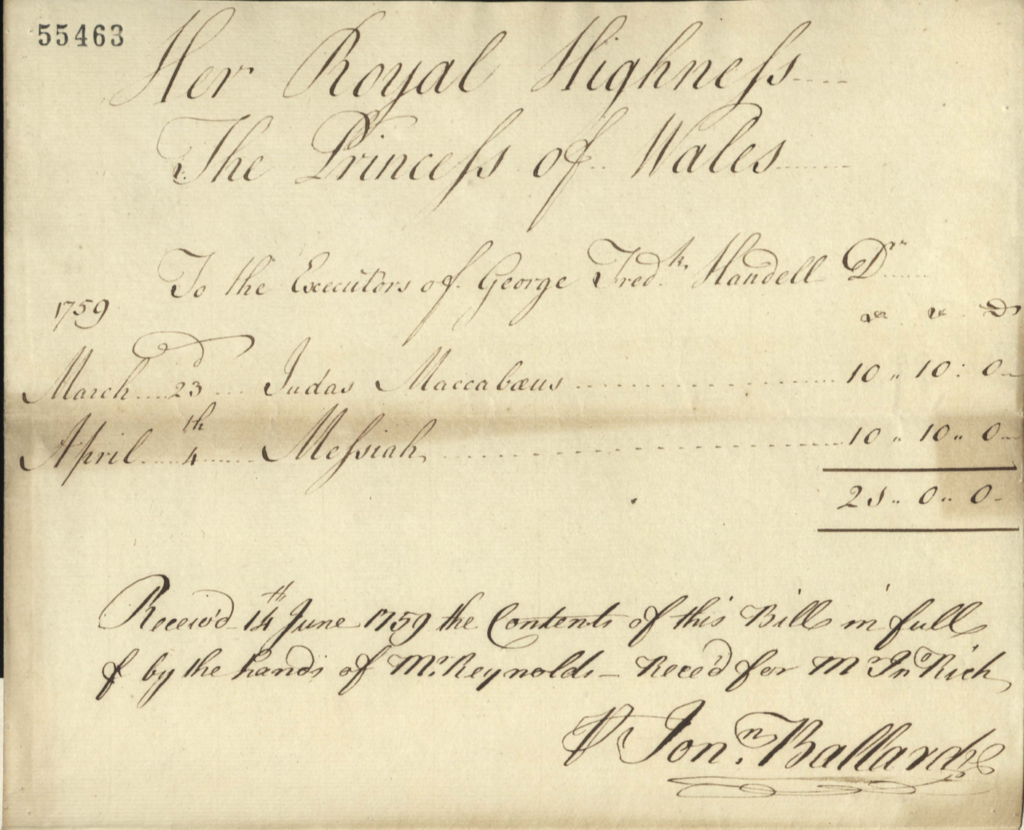

Receipt for payment received by the executors of Handel’s estate, for Princess Augusta’s attendance at two oratorios. GEO/MAIN/55462

The Princess attended “Judas Maccabeus” on March 23, 1759, and “Messiah” on April 4, 1759. This was the last production of “Messiah” that Handel attended himself; he attended the April 6 performance and died eight days later, on April 14. 1759. When it came time for the Princess to reckon her accounts, she didn’t pay Handel–she paid his estate £21 for her attendance at those two performances on June 14, 1759. While we cannot speculate on whether or not the Princess enjoyed the performances, or what she thought about Handel himself, this document does tell us that musical performances continued to be an important part of her public life after the death of her husband–and gives a glimpse into the popularity of that most famous of oratorios, the “Messiah.”

To see the score of the Messiah at the British Library, click here.

To hear a sing-a-long version of the Hallelujah Chorus, click here.

References:

Carole Taylor, “Handel and the Prince of Wales,” The Musical Times 25 no. 1692 (February, 1984), 89, 91-92.

David Hunter, The Lives of George Frideric Handel (Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2015).

Jonathan Kandell, “The Glorious History of Handel’s Messiah,” Smithsonian Magazine (2009), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-glorious-history-of-handels-messiah-148168540/.