“An Unbeliever as to the Rabbits”: Princess Caroline and the Case of Mary Toft

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

“I am transported, my dear friend to understand that your friend is as much an unbeliever as to the rabbits as I am.”

Queen Caroline, by Jacopo Amigoni. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

So wrote Princess Caroline, wife of George, Prince of Wales (the soon-to-be George II) to her friend Mrs. Clayton, one of her Women of the Bedchamber, sometime in November or December 1726 (GEO/ADD/28/111; GEO/ADD/28/010). We don’t know who the friend the Princess is referencing, and perhaps that doesn’t matter. But what does she mean when she says she is “an unbeliever as to the rabbits”? Because the letter isn’t dated, we don’t know for sure, but it’s highly likely that she’s referring to an incident that went 18th-century-viral: Mary Toft, the woman who gave birth to rabbits.

In April, 1726, Mary Toft, a peasant woman from Surrey, saw a rabbit in a field and chased it. Five weeks pregnant, she dreamt of rabbits and craved rabbit meat, but as a poor woman, couldn’t afford any. Seventeen weeks later, she miscarried and lost the baby she had been carrying. Toft became ill three weeks later, and lost what seemed to be parts of a pig, as though she were continuing to miscarry. She continued to bring forth animal parts, and eventually her mother-in-law, Ann, called in the local man-midwife. John Howard delivered Mary Tofts of animal feet, heads and skulls, and cheeks–parts that the Tofts claimed were rabbits.

Mary Toft, in an engraving based on a 1726 painting by John Laguerre.

Howard, who apparently believed the story, moved Mary Toft to a local inn, and began reaching out to his London contacts, summoning them to come and see her. Toft became an object of curiosity, and doctors from around the country came to witness the “monstrous births”. The King himself ordered that she be moved to London, so she could be examined by his doctors–and put on public view. George I sent his doctor, Nathaniel St Andre, to examine Mary Toft. Andre was impressed, and later published a pamphlet attesting that Toft had in fact given birth to rabbits. The Prince of Wales sent his own doctor to verify the findings of his father’s doctor, a symptom of a larger mistrust between father and son. Other doctors, including Sir Richard Manningham and James Douglas, dismissed Toft as a fraud and kept their distance from the case entirely.

Toft was confined in London, gawked at, and interrogated by doctors to the point of exhaustion and despair. At one point, she confessed to suicidal feelings.

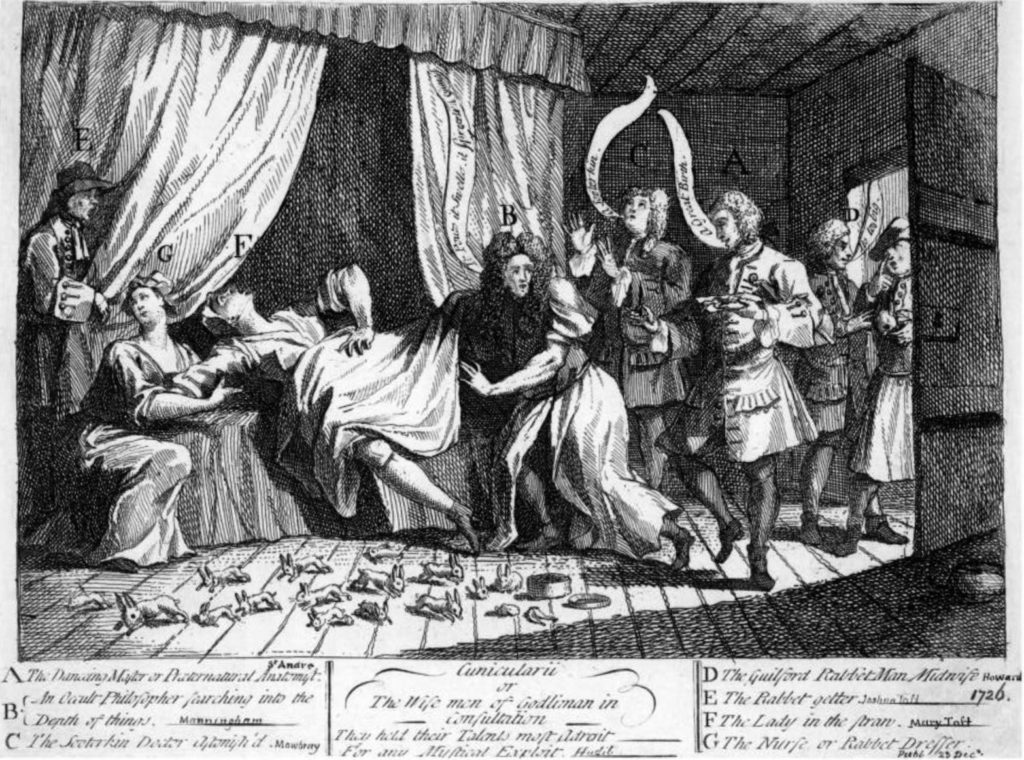

Engraving of Mary Toft by William Hogarth.

Eventually, after Sir Richard Manningham threatened to conduct “a very painful Experiment” upon her, Toft confessed to perpetrating a fraud. Toft ultimately confessed three times. First, she said that the wife of a wandering knife-grinder had told her that she could make some money by pretending to birth rabbits. In her second confession, the knife-grinder’s wife vanished, to be replaced by her mother-in-law and husband, who pushed Toft to perpetrate the fraud. In her third and final confession, Toft took all the responsibility. She was sent to prison, where she became very ill (unsurprisingly). She was released a few months later, in April 1727, as authorities couldn’t decide which statute to charge her under. She returned to her husband and probably had at least one more child, and died in obscurity in Surrey around 1763.

Mary Toft’s story circulated widely around the nation; people ate up the story of the woman who gave birth to rabbits. At the odd juncture of science and satire, her case–and the writings around it–show a conflict between “old” and “new” knowledges about women’s bodies. Mary Toft (or her mother-in-law?) used an “old” belief–that what a mother saw during her pregnancy influenced her baby’s physical aspects–to convince people that she could, indeed, have given birth to rabbits. In direct contrast, the physicians–both those who believed her and those who didn’t–used “new” understandings of human anatomy and processes of scientific reasoning to assess Mary Toft’s case and try to situate it within accepted “scientific” understandings of what was possible for the human body.

People across the country argued about whether or not they believed in the case of the monstrous rabbit births, and Princess Caroline was no different. Princess Caroline had been raised at Enlightened courts from the age of thirteen, and corresponded with philosophers and thinkers like Gottfried Wilhelm Liebniz (a mathematician and philosopher) all her life. An educated woman, she typified the “Enlightened Princess.” She knew that it was impossible for a woman to give birth to rabbits; she also knew that Mary Toft’s case could become part of the ongoing battle between George I and the Prince of Wales for public influence. Princess Caroline’s “unbelief” in the rabbits is more than just a snarky aside between friends. It’s a comment on topics ranging from trust and knowledge to women’s health and reproduction in the eighteenth century.

References

GEO/ADD/28/111; GEO/ADD/28/010

Nathaniel St. Andrè, A Short Narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets… (London: Printed for John Clarke, 1727), https://archive.org/details/shortnarrativeof00sain.

Lisa Foreman Cody, Birthing the Nation: Sex, Science, and the Conception of Eighteenth-Century Britons (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Karen Harvey, “What Mary Toft Felt: Women’s Voices, Pain, Power, and the Body,” History Workshop Journal (2015) 80 no. 1, 33-51.

Karen Harvey, The Imposteress Rabbit Breeder. Mary Toft and Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Stephen Taylor, “Caroline [Princess Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach],” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography September 23, 2004.

The friend of Mrs Clayton mentioned in the opening sentence above is probably Dr Friend. In the letters from Princess Caroline to Mrs Clayton the Princess uses the phrase “your friend” several times as an indirect reference to Dr Friend, whom she clearly admires. It makes sense that she is “transported” to hear that he doesn’t believe in the rabbits any more than she does. (see GEO/ADD/28/141)

On 25 October 1727 Dr John Friend (more correctly FREIND) became first physician to Queen Caroline, but he died in July 1728 after less than a year in the post.

[…] How could a woman give birth to a rabbit? […]

[…] subjects of gossip across the continent and in newspapers there is a strong probability that, like Mary Toft and the birthing of rabbits story, they will be […]