Cutting, Slicing, Pasting: Royal Female Friendship and Domestic Craft

by Dr Madeleine Pelling (University of York)

For elite and middling women in the eighteenth century, handicrafts including embroidery, decoupage, wood-cutting, turning and spinning were important activities in performing female sociability and manifesting rustic and picturesque ideals. The Georgian Papers Programme has recently digitized a key, though overlooked, album of cut-paper designs created by the artist and Bluestocking Mary Delany (1700-1788) and gifted to Queen Charlotte in 1781. This artefact, which covers twenty pages forming blue grounds and contains one hundred and fourteen individual paper cut designs from intricate and realistic botanical representations to more abstract decorative motifs, signals the value of such works as the material spaces of female sociability. Despite the wealth of scholarly attention paid to Delany and her craftwork, the album has been largely overlooked in discussions of the social function and artistic value of her work. In 2017, it formed the basis of my research as part of a GPP fellowship at the Windsor. I presented this research at the ‘Collage, Montage, Assemblage: Collected and Composite Forms, 1700 – Present’ conference at University of Edinburgh in April 2018, and an article based on this work was published in Journal 18 and can be read here.

Fig. 1 Mary Delany, Page with cut-paper cupid, flowers, women and children in an album of decoupage gifted to Queen Charlotte, 1781. GEO/ADD/2/65. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Mary Delany, born Mary Granville in Ireland in 1700, is known today for her famous botanical paper mosaics – cut and coloured paper arranged on black grounds to resemble botanical specimens taken from a number of elite sites including Kew Gardens, Kenwood House and Bulstrode Park. Throughout her life, Delany was a regular visitor to Bulstrode, home to her close friend, the widowed Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, 2nd Duchess of Portland (1715-1785). In May 1768, the duchess wrote to Delany’s niece that ‘she could spend every summer with her friends [at Bulstrode], who would be so happy to have her company’.[1] There, Delany began to develop a bold artistic style, one that has enjoyed a rich and important legacy.[2] During this period, King George III and Queen Charlotte were regular guests of the duchess and witnessed Delany at work. The queen was particularly taken by Delany’s creativity and, over several years, the two began to exchange craft works, tools and instruction between Bulstrode and Windsor. Following the duchess’s death, the king and queen granted Delany an allowance of £300 per annum and gifted her a house in Windsor, close to the royal residence, where she was regularly welcomed as a guest and witness to their private domesticity.

As part of my GPP King’s summer fellowship, I examined a range of materials – from art works to account books – that revealed not only the vibrancy of a domestic handicrafts practised by Charlotte and her daughters, but the enduring legacy of Delany’s exchanges with the queen. At Windsor, as well as at the Charlotte’s Frogmore estate, the royal women undertook projects in découpage, embroidery, sketching, spinning and turning, with the results of this work often contributing to the fabric of the interior environments in which they lived. At Frogmore, for example, Princess Elizabeth decorated the Cross Gallery with botanical paintings and paper-cuttings pasted onto the walls.[3] In her diaries, the queen recorded the programme of arts education undergone by her daughters and, often, directly overseen by her. Many of Charlotte’s diary entries give accounts of their activities; ‘We breakfasted at 9. At 10 the princesses went a Painting‘[4] and on another occasion, ‘staid together till 10, when the Younger princesses went home & the Eldest to their Drawing Masters’.[5]

Princess Charlotte’s account books reveal regular purchasing of arts materials and tools. In January 1808, the Princess Royal paid ‘Ackerman’s bill for fancy papers’, costing thirteen shillings and six pence.[6] Rudolph Ackermann (1764 – 1834), a famous purveyor of art works and artist’s materials whose repository was situated on The Strand, was a supplier to the royal family and appears elsewhere in Charlotte’s accounts. On 8 June of the same year, the princess settled an account there for the amount of one pound, three shillings and six pence, suggesting a regularity in her ordering habits.[7] For February 1809, listed amongst Charlotte’s new acquisitions are ‘2 pair of Sissers [sic] with files’, likely used in paper-cutting and embroidery, whilst in January 1811, she acquired ‘a Knife’ for five shillings.[8]

Fig. 2 Henry Edridge, Princess Elizabeth (scissors in hand!), 1804. Pencil and grey wash, 32.1 x 22.5 cm. RCIN 914247. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

In July 1808, Princess Elizabeth produced her own album of paper-cuts, bound in dark green leather and fastened at a silver clasp stamped with her cypher. Created at Windsor, this album appears to have been an organic project created over a number of months, possibly years, and containing works by the princess alongside those of other artists also working in paper-cuts. Previously, Jane Roberts has associated the album with Sarah Sophia Banks.[9] Sarah Sophia, sister to Sir Joseph Banks, was an avid collector of paper ephemera and friend to the princess. Certainly, the album contains materials that relate directly to her; A poem, written on a loose sheet of paper in Princess Elizabeth’s hand and inserted into the album gives further proof that, like Delany’s album twenty-seven years earlier, the princess’s work can be read in a context of elite female friendship. It reads:

Sophia Zarah [sic] Banks – Genius, good sense, and Friendship kind, Must ever bring you, to my mind. Eliza [10]

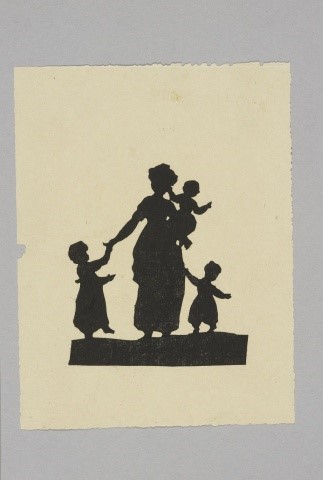

Fig. 3: Monograph silhouette produced by woodcut from an album of cuttings made by Princess Elizabeth, daughter of George III, and given by the Princess to Lady Banks, c. 1807-8. RCIN 1047678.u. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Containing black and white paper-cuts, ink-printed woodcuts, sketches and dried flowers, the album is tied with a purple ribbon, recalling the ribbon wrapped around the boards of Delany’s 1781 album and echoing the aesthetics of elite friendship that governed models of exchange between Bulstrode and Windsor two decades earlier.

Despite being created almost thirty years after Delany’s album was gifted to Queen Charlotte and entered her collection at Windsor, many of Princess Elizabeth’s creations in the album bear striking similarities to her designs. In particular, a woodcut printed onto loose paper in black ink, depicting a rustic group of children and women engaged in play (fig. 3), prompts significant comparisons with the earlier cuts of Delany’s 1781 album. This suggests that Delany’s own work was, at the very least, part of a broader artistic culture at the royal court, if not functioning as a direct point of reference or directory of design from which the princesses and other court ladies were working.

Dr Madeleine Pelling completed her PhD at the University of York, where she was the recipient of the History of Art Department doctoral scholarship. Her research concentrates on material and visual culture in the eighteenth century, with particular focus on the history of collecting and women as antiquarians. She is currently preparing a monograph, The Portland Museum: Collecting, Craft and Conversation, c. 1750 -1786, for publication. She has published articles in Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Journal 18 and Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, and held a Georgian Papers Programme King’s College London summer fellowship in 2017 . She has also been a recipient of a Lewis Walpole Library travel grant.

Dr Madeleine Pelling completed her PhD at the University of York, where she was the recipient of the History of Art Department doctoral scholarship. Her research concentrates on material and visual culture in the eighteenth century, with particular focus on the history of collecting and women as antiquarians. She is currently preparing a monograph, The Portland Museum: Collecting, Craft and Conversation, c. 1750 -1786, for publication. She has published articles in Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Journal 18 and Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, and held a Georgian Papers Programme King’s College London summer fellowship in 2017 . She has also been a recipient of a Lewis Walpole Library travel grant.

NOTES

[1] The duchess of Portland to Mary Dewes, May 1768, Lady Llandover (ed.), The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs Delany, 6 vols (London: Bentley, 1861-2), vol. IV.146.

[2] For more on Delany’s art, see Mark Laid and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts (eds), Mrs. Delany & Her Circle (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009); Ruth Hayden, Mrs Delany and Her Flower Collages (London: British Museum Press, 1980); Molly Peacock, The Paper Garden: Mrs Delany [Begins Her Life’s Work] at 72 (London: Bloomsbury, 2010). For more on Bulstrode Park and the Duchess of Portland, see Beth Fowkes Tobin, The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014); Madeleine Pelling, “Collecting the World: Female Friendship and Domestic Craft at Bulstrode Park,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 41, no. 1 (January 2018): pp. 101-120.

[3] There has been little scholarly focus on Elizabeth’s work at Frogmore, or indeed on the site as one of elite female crafting more generally.

[4] Queen Charlotte’s Diary, GEO/ADD/43/2, f. 5.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Princess Charlotte’s Account Books 1809-1811, GEO/ADD/17/82.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Roberts, George III & Queen Charlotte, 85-87.

[10] Note addressed to Sophia Zarah Banks, RCIN 1047678.b. The Royal Collection, Windsor.