George IV, Prince of Wales, and the Habits of the Masquerade

Meg Kobza is a third-year PhD candidate at Newcastle University, where she is working on the social history of the eighteenth-century British masquerade. Her research will shift the paradigm of scholarship on the masquerade away from literary analysis, which depicts the masquerade as a purely carnivalesque and debaucherous entertainment that flouted social distinctions. She argues instead that the masquerade was an exclusionary entertainment, moving horizontally between sites of social differentiation including opera houses, pleasure gardens, assembly rooms, and country houses. Meg was awarded the BSECS President’s Prize for best postgraduate paper in February 2018 and presented a draft of her article, ‘Dazzling or Fantastically Dull: Re-examining the Social History of the Eighteenth-Century London Masquerade’ at the Institute of Historical Research. Meg has also been awarded the Georgian Papers Program Fellowship from the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, which she completed in the summer of 2018.

When I started my fellowship in the Royal Archives, I was hopeful, but not entirely sure I would find anything relating to the eighteenth-century masquerade. However, His Royal Fashionable Highness, future George IV, was kind enough to bequeath me some particularly useful nuggets about his experiences with the masquerade. The Prince of Wales’s account books provided me with not only insight on purchasing habits, but also which habits he chose to wear and his knowledge of the masquerade itself.

While the Prince of Wales’s records of the masquerade are the only remaining ones in the Royal Archive, he was not the first of the Hanoverians to frequent this expensive leisure entertainment. George’s grandfather, Frederick, Prince of Wales, and great-grandfather, King George II, were both patrons of the subscription masquerade in its earlier days. Like George IV, they attended several subscription masquerades at King’s Theatre, which were hosted by the impresario J. Heidegger. Though masquerades were often under the censure of the Bishop of London during the first half of the century, George II so enjoyed them that he declared, ‘that whilst there were Masquerades, he wou’d go to them’ in front of the Bishop himself.[1] Given the history of strained relationships between Hanoverian fathers and sons, it not surprising that George III took an opposing stance and strongly disapproved of his children ever attending the masquerade. After learning of the Prince of Wales’s attendance at a masquerade in 1780, George III made his opinion very clear, warning, ‘you already know my disapprobation of [Masquerades] in this Country, and I cannot by any means agree to any of my children ever going to them’. Despite, or perhaps in spite of, his father’s objections to the masquerade, the Prince of Wales continued to attend those held at the Pantheon and Carlisle House with newspaper reports, manuscripts, and account books providing a paper trail of his habits.

Armed with some knowledge of the Prince of Wales’s attendance records at masquerades and a list of masquerade warehouse owners, I started looking through the stacks and stacks (and stacks) of his account books and bills of sale. Using the card index to identify haberdashers and habit makers allowed me to narrow my search and find several bills of sale relating to purchases made explicitly for masquerades. The Prince of Wales certainly had a sense of humour and a creative streak, exhibited through his choices of costume and continual purchases of fake noses.

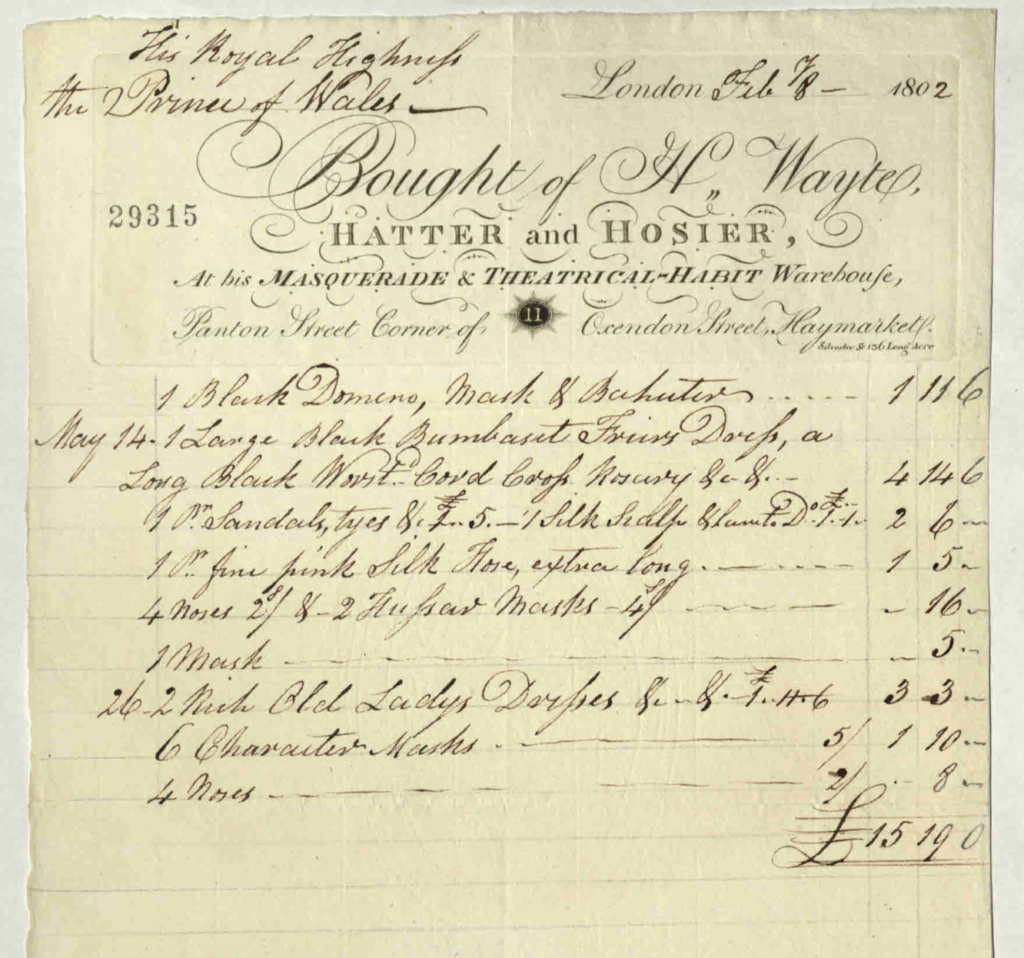

The Prince of Wales’ costume bills. The bottom line notes the purchase of four false noses at 8 shillings apiece. GEO/MAIN/29315

This example bill of sale from H. Wayte (above) provides an itemized list of costume pieces, revealing the Prince of Wales’s selections to include a friar and an old lady. His purchase of two ‘Rich Old Ladys Dresses’, additional accessories, masks, and fake noses suggest that these costumes were for his and possibly another’s use. It was not uncommon for the Prince of Wales to attend the masquerade with his uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, or a coterie of nobility in complementary costumes. Other masquerade bills of sale show similar signs of ‘group’ purchases, with multiple masks and fake noses appearing on each.

The chronology of these purchases gives additional insight regarding the lifespan of the masquerade habit and the consumer experience. As the bill of sale shows, the Prince of Wales purchased a ‘Black Bumbaset Friars Dress’ and domino on May 14th, followed by two new ‘Old Ladys Dresses’ less than two weeks later. The recurring purchases of dominos and character costumes, specifically the old lady habit (bought again in 1803), present the masquerade habit as a single-wear item. Newspaper reports and supplementary manuscript accounts reveal comparable habits among the beau monde, showing that the habit of wearing new habits was not exclusive to the nobility. The listed prices for masks, habits, and accessories were not unique to His Royal Highness either. Masquerade warehouses sold masks at an average of five shillings and dominos at ten shillings and six pence, making the minimum cost of a costume fifteen shillings and six pence. This expense, when combined with the purchase of a two guinea ticket, was far from affordable and limited 96% of London’s population from attending the masquerade, however infrequent.

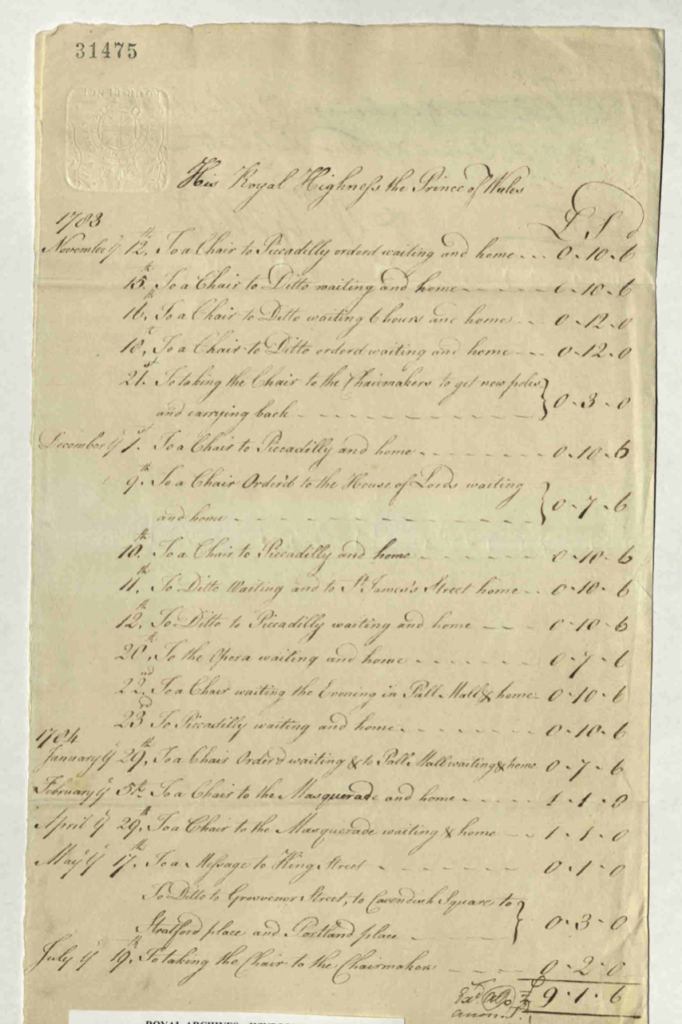

The Prince of Wales’s paper trail to the masquerade also includes records of his transportation to the entertainment. Differing from his normal travel expenses, the cost of the Prince of Wales’s chair to and from the masquerade was one guinea – more than twice the fare to and from the opera.

Bills for chair service for the Prince of Wales. GEO/MAIN/31475.

The rates listed in the Prince of Wales’s accounts align very closely with the average chair rates within London, showing that this pricing was not dependent on the status of the individual, but rather the status of the entertainment.

While bills of sale provide substantial information about the Prince of Wales’s spending habits and cost to attend the masquerade, they can be a little dry and don’t fully tell us how much, if at all, the Prince of Wales was invested in the fashionable entertainment. The correspondence between George and his brother, Frederick, fills in these gaps, showing that His Royal Highness not only attended masquerades, but had a strong working knowledge of costume design, execution, and etiquette. Charged with the responsibility of purchasing masquerade habits on behalf of Frederick, George went above and beyond Frederick’s request for a single habit. He ordered his brother three Vandyke dresses with explicit instructions on how and when they were to be worn. Upon sending the first of the habits in 1781, he wrote:

“Yr. Vandyke dress is compleat & beautiful; ye hat for it I have ordered of Cater; it was made by ye tailor to Covent Garden Theatre. Ye ruff belonging to it is separate from ye whole & ties with two little white strings & tassels. I do not mean it is a ruff, but lace; it is an imitation only, but very beautiful in ye shape of our shirt collars, only deeper. Remember yr. shirt collar or stock must not appear in this dress; you had therefore best not wear any stock at all & tuck yr. collar down or under. I flatter myself you will find all these things executed with yt. dernier gout, wisdom & propriety you attribute to me in propria persona.”[2]

George’s clear instructions on how to wear the Vandyke habit indicate his familiarity with dressing for the masquerade and a fluency in fashionable costumes. This is also seen in his later commission of an additional Vandyke dress, summer masquerade dress, and accompanying hat for Frederick, ensuring his brother is properly supplied for the entertainment in the upcoming months.[3]

As an active patron of (and participant in) the masquerade, the Prince of Wales’s records have been extremely useful in reconstructing a first-hand masquerade experience. His purchasing habits and knowledge of masquerade dress reveal his interest in the entertainment, while the costs of costumes and travel indicate the masquerade was a fashionable, elite space of the beau monde. Attending the masquerade, it seems, was a Hanoverian habit that could not be broken.

[1] Vanbrugh, p157-8, Feb 18, 1724, letter to Lord Carlisle

[2] Aspinall, Vol I: 1770-1789, Letter Set 42, 10 April 1781, p57

[3] Aspinall, Letter Set 45, p62.