International Politics by Proxy: The Marriage of Princess Louisa, 1743

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

Princess Louisa (or Louise) of Great Britain was the youngest daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach.[1] Born in 1724, she married Prince Frederick, the future King of Denmark in 1743…twice. Her first wedding was by proxy, and in the recently digitized Georgian Papers is the letter of attorney sent by Prince Frederick which authorized Louisa’s brother, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, to act as his proxy at the wedding ceremony.[2] While royal weddings garner plenty of public interest today for the pomp and circumstance that surround them, eighteenth-century royal weddings were as much about politics as they were about public perception. Marriage by proxy was one way to ensure that a politically engineered royal marriage took place as quickly as possible to cement alliances and safeguard the interests of all concerned.

Louisa of Great Britain at age 23, by Danish court painter Carl Gustav Pilo, 1747.

Princess Louisa’s marriage to Prince Frederick of Denmark was part of political machinations to protect British interests and preserve the balance of power in Eastern and Northern Europe. Frederick I of Sweden had no heir; Karl Peter Ulrich, the 13-year-old Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and the great-grandson of Charles XI of Sweden, was the most likely choice. In November 1741, Karl Peter converted to Russian Orthodoxy and repudiated his claim to the Swedish throne in favor of becoming heir presumptive to his aunt, Empress Elizabeth of Russia.[3]

Empress Elizabeth of Russia proposed Adolf Friedrich, prince-bishop of Lübeck and Peter’s cousin, as an heir for Sweden, and suggested that Adolf Friedrich might marry one of George II’s daughters, in order to minimize British objections to Russian machinations. George II didn’t love this idea, and turned instead to Denmark. British relations with Denmark had been strained by disagreements over the Hapsburg succession in the late 1730s, in the lead-up to the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748). Princess Louisa’s marriage to Frederick, Crown Prince of Denmark, was part of a series of political moves designed to advance British interests in northern Europe. Meanwhile, Christian VI, King of Denmark, hoped that this marriage would encourage the British to support Frederick, Louisa’s husband-to-be, as a candidate for the throne of Sweden. (This did not happen; the British remained officially neutral, but secretly supported Adolf Friedrich, the chosen candidate of Empress Elizabeth.)

Frederick V of Denmark, painted by Danish court painter Carl Gustav Pilo.

The treaty sealing Louisa’s marriage was signed on September 14, 1743 and Louisa left London on October 19 to marry a man she’d never met. Upon her arrival in Hanover, Louisa prepared for her wedding ceremony, and in the church at the Leine Palace, she professed her marriage vows to her brother William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.

Marriage by proxy was common in political marriages like this one. It was often more important to seal an alliance quickly than it was for the bride and groom to be present. Thus, royal brides often found themselves professing wedding vows twice: once in the proxy ceremony, and a second time upon their arrival in the groom’s country (almost all royal marriages conducted this way involved women leaving their homes for their husbands’, rather than the other way around).

But who could be a stand-in at a proxy wedding? When Henrietta Maria of France married Charles I of England by proxy in May 1625 at Notre Dame in Paris, Charles de Lorraine, Duke of Chevreuse, stood in for the groom. Chevreuse was close to Henrietta Maria, and traveled with her to England after her marriage.[4] A proxy was frequently someone important to the political interests of the bride’s family, someone she knew and who was favored by her family.

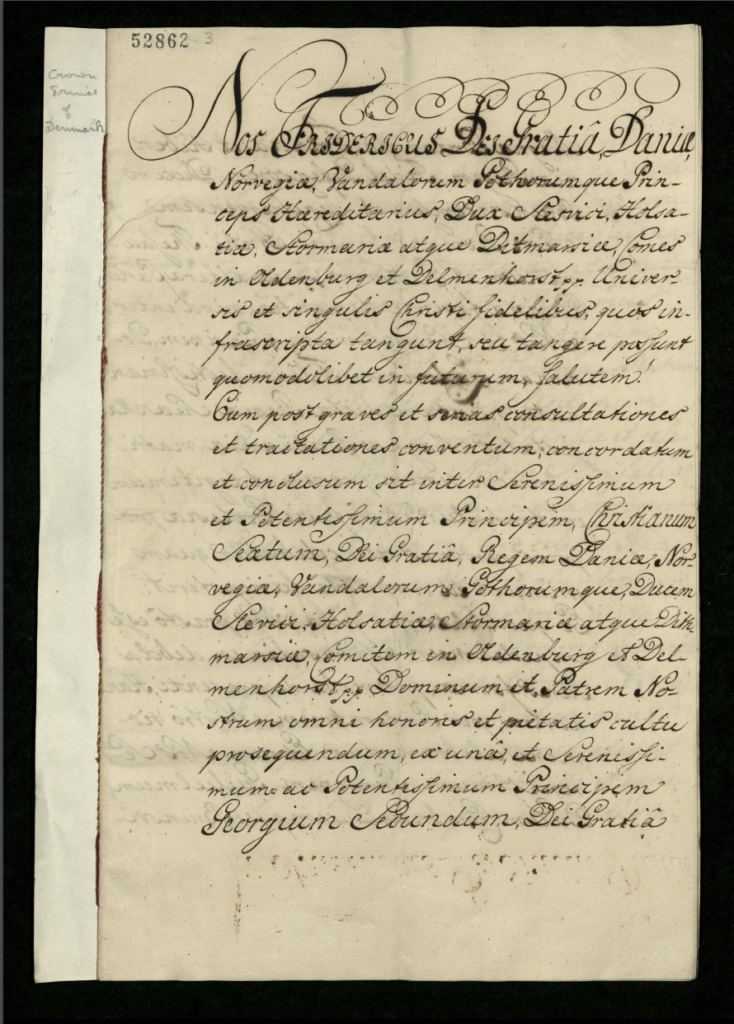

The document granting William Augustus legal status as Prince Frederick’s proxy. Click the image to see the entire document.

GEO/MAIN/52682-52683

Louisa’s brother William Augustus checked all those boxes. He was his parents’ favored son (though not the heir), an experienced soldier, and betrothed to Princess Louise of Denmark as part of the same agreement that joined his sister Louisa to Prince Frederick (though William Augustus’ marriage fell through). While it’s unclear how close the siblings were personally, William Augustus was family. But in order to stand in for Prince Frederick, William Augustus needed legal authorization, which Prince Frederick had sent to Hanover just before the wedding. This document, in formal legal Latin, authorizes William Augustus to act as Frederick’s stand-in in a ceremony of “true, pure and legitimate marriage” (“matrimonium verum, purum et legitimum”).[5] This proxy marriage sealed the formal alliance, and solidified the English agreement with the Danish as Louisa continued to travel towards Denmark.

When she arrived in Copenhagen, Louisa and Frederick married again, this time with both the bride and groom present, at Christiansborg Castle on December 11, 1743. Her marriage was celebrated in England as part of successful diplomatic negotiations in northern Europe. In the London Gazette, officials from the town of Cambridge publicly congratulated the king on “the Strengthening of the Protestant Interest [in Europe] by the Marriage of Her Royal Highness the Princess Louisa.”[3]

Louisa and Frederick had five children, despite Frederick’s philandering, alcoholism, and violent tendencies. On the death of Frederick’s father, Christian VI, in 1746, Louisa became queen consort, but never exercised much political power. She died at age 27 after complications from a miscarriage. Her marriage by proxy was one part of Great Britain’s diplomatic toolbox. Louisa was not the first, nor the last, European princess to be married by proxy, but the presence of this authorization document among the Georgian Papers reminds us how little control royal women often had over decisions about their marriages, and of the continuing importance of kinship in European diplomacy in the eighteenth century.

[1] In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, she is named as Louisa, and I follow that convention. Matthew Kilburn, “Louisa, Princess (1724-1751)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online ed., May 9, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2019. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxy.wm.edu/view/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-112760?rskey=eK32dO&result=2

[3] Karl Peter, later Peter III of Russia, was unpopular and ruled for less than a year before being deposed by his wife, Catherine (later known as Catherine the Great) on July 9, 1762, and dying in murky circumstances a week later.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Peter III,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 14, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Peter-III-emperor-of-Russia

[4] Caroline M. Hibbard, “Henrietta Maria [Princess Henrietta Maria of France] (1609-1669), queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, queen consort of Charles I.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online ed., September 23, 3004. Accessed July 29, 2019. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxy.wm.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-12947?rskey=ZtdxMS&result=2

[6] London Gazette, December 13, 1743, pg. 3. Accessed July 29, 2019. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/8284/page/3