The Funerals of George III

By Karin Wulf

Karin Wulf is Executive Director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Professor at William & Mary, and US Academic Director of the Georgian Papers Programme

__________________

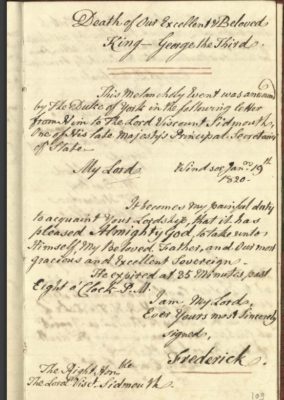

He expired at 35 minutes past Eight o’Clock

From Frederick, Duke of York

His majesty expired without pain

From the king’s physicians

Guns shall be fired tomorrow at the rate of one Gun every five Minutes from Eight o’clock tomorrow morning, till the Procession for the funeral shall begin to move which will probably be about 9 in the evening.

After the Funeral Service and the Anthem, the Coffin lower’d gradually to the Royal Vault, and disappeared from Sight.

From Robert Greville

King George III’s death on 29 January 1820 was a sombre event. Having been ill for the last ten years of his life, stricken with the mental illness that had plagued him at other moments, most remarkably in late 1788 and early 1789, he also suffered from afflictions including blindness. He missed celebrating his diamond jubilee by less than a year. He was, at the time of his death, the longest reigning British monarch.

The king’s death, funeral and commemoration were preceded by nearly two decades of royal burials at St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle, including an intense several years after 1817. One of George’s sons, Edward Duke of Kent (father of Queen Victoria), died just a few days before his father and was buried a few days earlier. The scholar Matthias Range notes, in British Royal and State Funerals since Elizabeth I (2016), that, for the king’s funeral, ‘the service itself included mostly the same music as the previous funerals’.

Although the funeral arrangements were designed to give some public access, and to mark the passing of the sovereign with dignity and respect, the organizers would have been extraordinarily well versed in royal funerary practices by the winter of 1820. Since 1805, beginning with the king’s brother, the Duke of Gloucester, royal burials had taken place in St George’s Chapel rather than at Westminster Abbey. The king wrote to his bereaved nephew in 1805 to let him know that this was the new plan, and he pointed out that this would shift the event from a ‘public’ to a ‘private’ service.

RA GEO/MAIN/16763 : King George III to his nephew, the new Duke of Gloucester, explaining that the latter’s late father had expressed a desire for burial at St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. Image: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020. To read the whole letter, click on the image; for a transcription, click here.

In November 1817 Princess Charlotte died in childbirth, alongside her stillborn son. It was a terrible blow to the royal family. As the only child of the Prince of Wales, she was expected to become queen. Her youth, and the contrast she provided to both her father and grandfather, made her a popular figure, and thus her loss all the more keenly felt. The American Louisa Caton Hervey (later the Duchess of Leeds) sent the news to a confidante, describing the princess’s death as ‘a terrible affliction to the whole country….we are all in the deepest mourning’. The funeral procession and service was captured by artists who conveyed both the solemnity of the event and the grandeur of the chapel.

The Princess’s funeral procession (RCIN 750745), and Richard Barrett Davis, The Queen’s Funeral Procession (RCIN 403548). Images: Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty the Queen 2020.

Just a year later, Queen Charlotte died. The funeral was discussed in the pages of the European Magazine for December 1818, in the same issue that profiled Sir Isaac Heard, the Garter King of Arms and thus the herald who would have been intimately familiar by that point with planning and executing state funerals. As this lengthy featured commenced, the writer noted that ‘the distinctions of birth, and the privileges of state, and the exemptions of Royalty, are all broken down by death’. That might be, but every detail of the royal event was noted, such as the interior of a lead coffin lined with ‘a mattress and cushion for the head, … embossed with white flos silk, upon a rich plain white satin, and an ample sheet of the same costly material’. The state coffin was of ‘Honduras mahogany’. As the queen was laid in the coffin, it was filled with spices.

A mourning ring with Queen Charlotte’s hair, just one of many such mourning objects some of which combined the hair of the king and queen. RCIN 4234. Image: Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty the Queen 2020.

The Queen’s death was understood to be a blow to the king, though by even public accounts he would not understand his loss. The European Magazine speculated that, for the Prince Regent, his mother’s funeral was a terribly sad echo of his daughter’s, but also a foreshadowing of his father’s. ‘Could he forget that … within the very precincts of that spot where the sad funeral pomp ushered one Parent to the sepulchre, another Parent, heavily stricken by the hand of Providence, a forlorn, venerable Father, wandered darkly through the chambers of his Royal Palace, unconscious — happily unconscious — of the mortality that had fallen upon his house.’

The European Magazine for December 1818 included a schematic of the funeral procession for Queen Charlotte.

It was just over a year later, on 29 January in the evening, when the king died.

Among reports of the king’s death, funeral, and burial is an account from his long-serving equerry, Robert Greville. Greville’s are some of the most notable comments on the king’s illnesses. By 1819 he had been dismissed from royal service, but he remained close enough to the household to make a record of the late sovereign’s death and commemoration, and most of what he wrote was copied from the newspapers including an ‘Extract from the detailed account of the Procession of the Interment of his Majesty George 3rd’ from ‘the Supplement to the London Gazette’. Greville wrote that his own name was listed in the procession, even though ‘I had no notice for Attendance of the Dear King’s Funeral, nor the least hint from any Quarter that such attendance from me was wished or Intended’. He also included a brief account of the king’s remains lying in state ‘in the Royal Apartments in Windsor Castle from Tuesday morning the 15th February 1820 at 9 o’clock until the time of his Interment on Wednesday Evening February 16th, 1820. The public were admitted from 10 o’clock to 4 on Tuesday and from 10 o’clock to 3 on Wednesday.’ After the extraordinary reign of George III, including his lengthy final illness, the king was laid to rest.

Robert Greville’s journal, with his account from page 109 of the Death of our Excellent & Beloved King – George the Third: RCIN 1047015. Image Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2020. To read the original in high definition, click on the image.

News of the king’s death began to be reported in American newspapers in March, reprinting ‘from English papers’, in particular the London Gazette, the notice of the king’s death and various other communications such as the convening of the Privy Council to recognize the new sovereign, George IV. A new Georgian era dawned.

[…] are a few of the maps that sparked George’s imagination. You can learn more about how history remembers America’s last king–in manuscripts, memories, medals, and […]