You Just Had to Be There?

Thoughts on Transcription, Inventories, and Materiality in Understanding Carlton House

By Ali MacDonald

Ali MacDonald is a graduate student and PhD candidate in the History department at William & Mary.

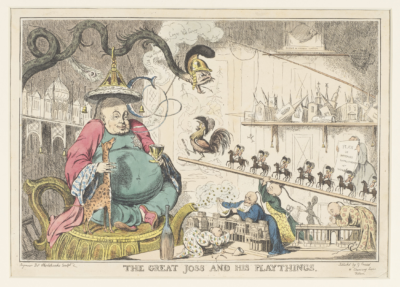

Last month I took a day out of my research trip to visit George IV: Art & Spectacle, currently on display at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (Nov 15, 2019 – May 3, 2020). In a sense this exhibition seeks to rehabilitate our long-standing conception of George as a bad son, bad father, bad husband, and bad monarch. George IV has largely lived on in popular memory through the satires that caricatured his fraught marital relationship – captured in print in the fabulous 1820 satire The Kettle calling the Pot ugly names –

his love of ‘oriental’ style art and architecture, and his gluttonous appetite and exorbitant expenditures. What we now value as important artistic contributions to the Royal Collection, contemporaries saw as extravagant and frivolous consumption practices that only further strained an already stretched economy in the years following the Napoleonic wars. Living up to its name, the exhibition shifts our focus away from satirical representations and on to the splendor of the collection George assembled. He may have been a gluttonous and self-indulgent man, but his consumption practices, particularly those for Carlton House, were part of a conscious effort to craft a collection that enabled both private amusement and arm-chair traveling as well as a magnificent public persona.

As a historian of material culture, the opportunity to visit The Queen’s Gallery is always a treat. But for me viewing this exhibition held more than the normal curiosity felt by an art historian on a Grand Tour. While studying for my PhD, I have had the pleasure of working with the Georgian Papers Programme in several different capacities. Most recently, I and two of my colleagues have been developing a project that examines the inventories created for Carlton House between 1792 and 1830. Over the past month I have transcribed lists of the material objects that were initially housed at Carlton House and, with its demolition in 1827, dispersed throughout the remaining royal residences.

The process of working methodically through these inventories conjured sumptuous images of singular objects. It is hard not to let your imagination run wild when reading the detailed language used to describe the materials – mahogany, rosewood, silks, stains, red Morocco leather – and the evocative descriptions of the design and decoration of each object – tables with “festoons of vine”, “very handsome bronze teapots”, lamps “enriched with female winged figures.” However, for me, one of the interesting things about inventories is that while they have the almost magical power of enabling the savvy historian to re-create non-extant material spaces, they can also de-materialize objects. In a sense, the process of listing objects removes some of the collective performativity that was so important for the complex rituals of self-fashioning and sociability. A table is just beautifully worked wood until it is covered with cards, a tea set, or place settings and used by a group of people. And most importantly, inventories do not always capture the visceral feelings that we have when we stand in front of an object. Anyone who has spent time watching the visitors in a museum knows that viewing objects in person can be captivating.

Thus, walking into the third room of Art & Splendor offered an entirely different encounter with the material objects that decorated Carlton House. Without re-creating its decorative scheme exactly, the third room in the exhibit seeks to capture some of the sensorial and material richness of Carlton House. Presented with Carlton House when he came of age in 1783, George spent forty years creating and re-creating colourful interiors with coordinated design schemes that included rich textiles, “beautifully formed” furniture, sculpture, porcelain, and Old Master paintings. It was at Carlton House that George first experimented with the ‘oriental’ style of design that he was satirized for, and that saw its full realization in the Brighton Pavilion.

Vignettes of coordinated interior design and George’s fascination with Chinese objects greet the viewer in the main Carlton House room. Moving clockwise around the space, Rembrandt’s Portrait of Jan Rijcken and his Wife, Griet Jans (‘The Shipbuilder and his Wife’) – for which George paid the princely sum of £ 5,250 – hangs above an oak commode (a decorative chest of drawers) inlaid with tortoiseshell, brass, pewter, and an assortment of coloured hardwoods. Resting on top of the chest of drawers are two small black and gold gilt Sèvres vases which flank a visually and technically magnificent Sèvres pot-pourri vase.

- Rembrandt et all

- Portrait of Jan Rijcken and his Wife, Griet Jans (‘The Shipbuilder and his Wife’)

- Sèvres porcelain factory, Pot-pourri à vaisseau

In some ways this is a relatively simple grouping; a single painting, a chest of drawers, and three vases. Yet seeing the five objects interacting with one another is a completely different experience than seeing five similar objects listed one after the other in an inventory. The stark white of the lace collars and head covering in Rembrandt’s Portrait of Jan Rijcken and his Wife, Griet Jans visually pull out the white details on the pot-pourri vase, while the creamy pinks in the marble top of the commode and the vibrant rosewood and coral tones in the petals of the tulips on the front of the chest amplify the rosy pink undertones Rembrandt used in the faces and hands of his sitters. Similarly, the rich black glaze on the paired vases makes the dark tones of the painting and the black backdrop on the commode appear more sumptuous. Both visually and sensorially then, pairing these five objects together creates a cohesive visual connection that enhances the objects and captivates the viewer in a way that is not possible, or at least not the same, in the process of transcribing an inventory.

It is not just the aesthetic connections that are important in this grouping. Yes, there are interesting design questions to be asked about style and decoration of each object but by placing these items together the curators have created an assemblage that also raises thought-provoking questions about the global networks embodied in the objects. Where were the materials for the commode sourced from? Who harvested the woods? Where will the shipbuilder’s ships sail? Who will be traveling on those ships? What will they be transporting? What is the role of women in the creation of these objects? Admittedly some of these questions can be asked after transcribing similar items from an inventory, but the connections between them and the ways in which their stories might overlap become more pressing when the surviving material objects are viewed together, and in person.

The Chinese objects on display in this room also prompt interesting questions. A pair of porcelain pagodas flanking a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough of George’s three eldest daughters are material embodiments of interconnectedness. The pagoda themselves were created in Jingdexhen, China between c. 1800 and 1815. Sometime after their arrival in Europe they were mounted on gilt bronze platforms not dramatically unlike the mount for the pot-pourri vase. Standing in front of this assemblage I wondered what this cultural layering can tell us about Europe in the early nineteenth century? This type of hybridity was not uncommon and can, in part, be captured in written descriptions. However, when they are viewed in person, the contrast between the smooth cool porcelain and the rich gilt has a tactile quality that cannot be captured in an inventory.

What is fascinating about any exhibition is that every person who visits will leave having experienced it differently. Certainly, I was struck by the formal spectacle and magnificence on display and George’s clear adherence to a specific type of taste. However, because of my work on the inventories and my background as a material culture historian, in many ways my experience of visiting the gallery became a personal meditation on the value of interweaving textual and material evidence in historical narratives. While it is easy to say that combining material and textual evidence is vital in the context of a royal collection where much of both have been carefully preserved, it is important to think about what each type of evidence can do in numerous other contexts. It also begs questions about how to reconcile these ideas in a digital project that is based on textual descriptions of objects. Luckily, many of the objects in the inventories can be traced in the Royal Collection, but how should we represent that in our project? Is it possible to give viewers of a digital narrative the same sensory or visceral experience that I had standing in front of George’s Rembrandt, viewing it not on its own, but as part of a coherent micro collection? These are questions that we will continue to work out as our project develops, but no matter what our solution ends up being, I believe it will be a richer project for having visited George IV: Art & Spectacle and viewing these objects in person.