Lord Erskine’s Lemons: A Poem on Van Dyck’s Margaret Lemon in Princess Charlotte’s Poetry Book

By Dr Jonathan Taylor, BSECS GPP fellow 2020.

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Margaret Lemon (fl.1635-1640) c.1638

Oil on canvas | 93.3 x 77.8 cm | RCIN 402531 (Image courtesy of Royal Collection Trust (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2020)

The Georgian Papers Programme has made available a digitized copy of a commonplace book of poetry that belonged to Princess Charlotte (1796-1817): GEO/ADD/22/95. Alongside numerous quotations from famous works, including Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion (1808) and The Lady of the Lake (1810), Charlotte transcribed a surreal Georgian poem inspired by Sir Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of his mistress Margaret Lemon (c. 1638), which has been part of the Royal Collection at Hampton Court Palace since before Charlotte’s birth, and which is reproduced above.

Peter Edward Stroehling (1768-c. 1826), Frederica, Duchess of York (1767-1830) [1807] Oil on copper, 61.1 x 47.7 cm RCIN 40504. Image courtesy of Royal Collection Trust (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2020.

The poem was written by Thomas, 1st Baron Erskine (1750-1823), a former Lord Chancellor, and addressed to Prince Adolphus (1774-1850), the Duke of Cambridge and seventh son of George III. According to Charlotte’s notes on the poem, which was probably written in 1811, Adolphus was a great admirer of Van Dyck’s intimate portrait of his mistress.[1] Written from Margaret’s perspective, the poem imagines that Margaret has been trapped in Van Dyck’s painting by the ‘magic wand’ of a dragon.[2] It begins with Margaret being ‘lur’d’ and seduced by the Duke of Cambridge’s ‘amorous smile’.[3] She escapes her portrait and seeks the duke when her captor is distracted by the beauty of Adolphus’s sister-in-law, the Duchess of York, the former Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia (1767-1820). However, afraid that she will be recaptured, Margaret flees to Hampton Court Palace’s greenhouse, where, apparently drawn by a sense of kinship, she transforms herself into a lemon and hides amongst her namesakes. Margaret then falls victim to a curse, which decrees that she will wither and die, unless she is picked before the sun sets. Fortunately, Erskine hears Margaret’s ‘sad desponding sigh’, plucks her from the lemon tree and presents her to Adolphus.[4] In her notes, Charlotte records that Erskine dramatically collapsed the boundary between reality and fiction by presenting the prince with one of the palace’s lemons, along with the poem, at dinner.[5]

Thomas Erskine by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1802). The original hangs in Lincoln’s Inn

Erskine’s poetic response to Van Dyck’s painting is a striking Georgian example of the workings of male gaze (the idea that cultural depictions of women typically sexually objectify the female body for the gratification of heterosexual men). The poem also literalises the objectification of women. Erskine not only encouraged Adolphus to indulge in the fantasy that his ‘amorous’ fascination with the subject of Van Dyck’s portrait had been reciprocated, but also presented the supposedly metamorphosed Margaret as an object for the prince to possess and enjoy.

The real Margaret Lemon appears to have been similarly prone to misfortune.[6] Denounced by the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar as a ‘dangerous woman’ and ‘demon of jealousy’ (he also claimed that she had attempted to bite off Van Dyck’s finger in a fit of jealousy), Margaret was abandoned by Van Dyck when (probably at the urging of Charles I) he married the Scottish noblewoman Mary Ruthven.[7] Ironically, Charles later purchased the artist’s portrait of Margaret for his personal collection. The ending of Erskine’s poem, which cautions the prince about enjoying his ‘prize’ by punning on the fact that lemons are ‘sour’, likely alludes to Margaret’s reputation for bitterness.[8] Margaret’s misfortunes continued after her separation from Van Dyck. As Hilary Maddicott has recently illuminated, she committed suicide with a pistol in 1643, shortly after discovering that another of her lovers had died fighting for the Royalists during the English Civil War.[9]

Adolphus Frederick, Duke of Cambridge (1774-1850)? [c. 1813] Watercolour on ivory | 4.5 x 3.7 cm | RCIN 420989. IMage courtesy of Royal Collection Trust, (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2020

Erskine, who served as Lord Chancellor during the short-lived Ministry of All Talents (1806-7), enjoyed good relationships with several members of the royal family besides Adolphus. He appears to have been particularly friendly with the Duchess of York, the ‘Royal Dame’ who catches the dragon’s eye and allows Margaret to slip from her frame.[10] Charlotte transcribed several other poems that Erskine wrote for the duchess, including one about a ‘hallowed little lock’ of the Whig politician Charles James Fox’s hair, which the duchess had sent to Erskine as a gift.[11] Erskine, who was also a Whig, used this poem to imagine the Britain that might have been had Fox (who had died in 1806) lived to become Prime Minister. The poem summons up ‘visions Vain’ of Fox returning from the ‘dark grave’ to ‘inspire cool noble virtuous thought’ and ensure Britain’s ‘proud & matchless liberty’.[12] In one line, Erskine toys with the idea of depositing the duchess’s gift as a relic in St Stephen’s Chapel (the House of Commons chamber in the old Palace of Westminster).[13]

Erskine’s Whig politics also made him a natural ally of Charlotte’s father, George, Prince of Wales. The Royal Archives holds records of Erskine’s support for, or role in furthering, several of the prince’s projects, including his push for a regency during George III’s illness in 1788, his quest to secure a military commission in 1798 and his attempts to penetrate the secrecy surrounding the recurrence of his father’s illness in 1804.[14]

Charlotte Jones (1768-1847), Princess Charlotte (1796-1817) [1816] Watercolour on ivory, 22.9 x 17.5 cm , RCIN 421470: image courtesy of Royal Collection Trust, (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2020.

Erskine’s relationship with Charlotte was more complicated. As Anne Stott has illuminated in her recent biography of Charlotte, Erskine had also been a supporter and confidant of the Prince of Wales during his campaign to wrest control of Charlotte’s upbringing from his father (a 1717 judicial ruling had established that the care and education of royal children were prerogatives of the sovereign rather than their parents).[15] One of George’s principal motivations for defying his father’s authority was to separate Charlotte from her mother, his estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick, for whom the king had developed a particular fondness. Although Charlotte evidently admired Erskine’s poetry (her letters to her friend Margaret Mercer Elphinstone indicate that she may have been particularly drawn to supernatural elements of his poem about Margaret Lemon), their relationship came under direct strain when Erskine sided with the Prince Regent during the very public battle of wills that took place between Charlotte and her father in 1814.[16] When Charlotte broke off her engagement to the Prince of Orange in June that year, George, who had strongly urged the match, threatened to place Charlotte under virtual house arrest and deny her all visitors except her grandmother, Queen Charlotte. Charlotte sensationally, but briefly, escaped to her mother’s house, before the Prince confined her to Cranbourne Lodge in Windsor.[17] Despite her enforced isolation, Charlotte successfully entreated her uncle, Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex (1773-1843), to raise the question of her independence in Parliament. The duke’s speech provoked fury amongst the regent’s circle and the Royal Archives holds a particularly stern letter that Erskine wrote to Charlotte on the subject, in which he reminds her of her ‘duty’ to her father and makes the extraordinary claim that her attempts to undermine George’s authority were directly comparable to the ‘spurt of insolent and atrocious defamation’ of monarchy that had brought about ‘the beginning of the French revolution’.[18] If Charlotte had her poetry book to while away the period of her confinement, she would no doubt have perceived the similarities between her plight and that of Erskine’s Margaret Lemon, who similarly perpetrates a brief escape from patriarchal oppression before Erskine puts her firmly back in what he evidently perceived to be her place.

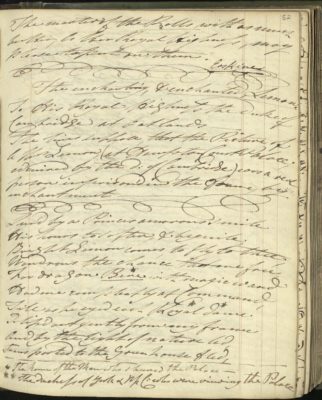

Transcript

The enchanting, & enchanted, Lemon

To His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge, at Oatlands

The lines suppose that the Picture of a Mrs Lemon (at Hampton Court Palace, admired by the D: of Cambridge) was a real person imprison’d in the Frame, by enchantment

————

Lur’d by a Princes amorous smile

His hours to soften, & beguile.

Bright Lemon comes, to fly to thee,

Wondrous the chance that me free,

For dragon Bene* with magic wand * The name of the Man who showed the Palace

Had me completely at Command,

Till as he eyed each Royal* Dame* ** The Duchess of York & P[rince]ss C. who were viewing the Palace

I slipp’d out gently from my Frame

And by the light of nature led,

Transported to the Green House fled,

And perch’d upon my parent tree,

Where other lemons, you might see,

But fastened there by Magic spell,

Soon had I touch’d the the gate of Hell,

For fate with sand glass holding high,

Pronounc’d this dreadful destiny,

“Unless before the sun descends,

The Branch that with thy trespass bends,

shall pass beneath a strangers power,

Prepare the[e] for the fatal Hour”

And now the glorious God of day,

Quench’d by the storm quick fled away,

And verging to the darkened main,

Portended every hope was vain,

With passions strong, but lost in Fears,

The frame was moistened with my tears,

Haply the bearer passing by

Pitied my sad desponding sigh

And singing on the enchanted bough,

Broke it, & here presents me* now, * (*The author of these impromptu lines had plucked a Lemon of the tree in the Palace

Should anyone with envious Eyes garden & at Dinner, presented it to the duke with these lines)

Hold light your unexpected prize,

Tell them, in the exulting Hour

That Lemons, like the grapes, are Soure.

NOTES

[2] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 52.

[3] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 52

[4] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 53.

[5] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 53.

[6] For the little that is known about Margaret Lemon’s life and death, see Hilary Maddicott, “‘Qualis vita, finis ita’: The Life and Death of Margaret Lemon, Mistress of Van Dyck”, The Burlington Magazine, 160 (February 2018): pp. 92-100.

[7] Maddicott, ‘Qualis vita, finis ita’, pp. 93-4.

[8] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 53.

[9] Maddicott, ‘Qualis vita, finis ita’, pp. 96-9.

[10] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 52.

[11] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 54.

[12] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 54.

[13] GEO/ADD/22/95, p. 54.

[14] GEO/MAIN/38261: Thomas Erskine to Captain John Willett Payne, 22 November 1788; GEO/MAIN/39509-39512: James Mansfield, Thomas Erskine, Robert Graham, Vicary Gibbs and William Adam to George, Prince of Wales, 17 May 1798; GEO/MAIN/40185-40187: Thomas Erskine to the Earl of Eldon, [2-3 June 1804].

[15] Anne Stott, The Lost Queen: The Life and Tragedy of the Prince Regent’s Daughter (Barnsley: Pen and Sword History, 2020), p. 59.

[16] For Charlotte and Margaret Mercer Elphinstone’s correspondence, see Arthur Aspinall (ed.), Letters of the Princess Charlotte, 1811-1817 (London: Home and Van Thal, 1949).

[17] For a detailed account of the Orange debacle and Charlotte’s imprisonment, see Stott, Lost Queen, pp. 140-81.

[18] GEO/MAIN/49860-49864: Lord Erskine to Princess Charlotte of Wales, 27 July 1814, fo. 7.

[…] different angle on Princess Charlotte’s life is provided in a blog post by Jonathan Taylor, this year’s GPP fellow supported by the British Society for Eighteenth Century Studies. His […]