Royalty on the Road: Insights into the Royal Visits of George III and George IV

By Paige Emerick, University of Leicester, GPP King’s College London Summer Fellowship 2019

When planning research trips for my PhD topic on the royal visits of George III and George IV, I knew a trip to the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle would be essential. After establishing the dates, locations, attendees, and itineraries of the visits across the reigns of the two kings, much of my research had centred around visiting local archives to uncover fragments pertaining to these visits. This included snippets in letters and memoirs by local inhabitants who witnessed the visits, trawling through newspaper collections to analyse the frequency with which the local and national press reported the visits, and accessing museum and art collections to understand how these momentous events were commemorated through visual and material culture. What was missing, however, were the sources to understand how the royal family themselves experienced and thought about travel, and the insider’s perspective into how these visits were organised and planned. My Georgian Papers Programme Fellowship in the autumn of 2019 provided me with access to the royal documents to be able to understand these important viewpoints.

George III’s Visits

The accession of the Hanoverian dynasty in 1714 marked a decline in royal visits around Britain, as both George I and George II disregarded the importance of being seen by their subjects outside of London to strengthen their personal popularity and the security of the kingdom from the Jacobite threat. Instead, these two kings preferred to regularly journey back to their homeland of Hanover in Germany which prevented them from developing a more personal and meaningful relationship with the British population. By the time George III ascended to the throne in 1760, there had been a hiatus in royal visits in Britain lasting nearly 50 years. Despite being very much an armchair traveller (as evidenced in his extensive topographical collection, now held by the British Library), George III was initially slow to adopt the use of travel.[1]

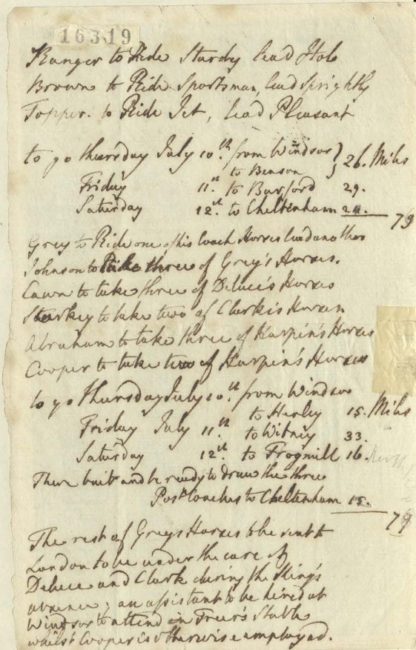

It was not until 1773 that George III first ventured further than Windsor or London by travelling to Portsmouth to oversee a naval review at the dockyard. Sifting through a box of George III’s miscellaneous papers revealed some of the initial logistical preparations needed in advance of this royal journey, including instructions for sending servants and horses out ahead of the King’s departure. These instructions listed details of dates, places to stay along the route, and the time and mileage between locations.[2] A similar itinerary survives for George III’s second visit to Portsmouth in 1778, this time accompanied by Queen Charlotte.[3] Later in 1788, upon his health deteriorating and with persuasion by his physician George Baker, George III was convinced to travel to Cheltenham to drink the restorative spa waters. Again, for this trip, there is a surviving memorandum in cramped handwriting listing servants, horses, and dates of travel.[4] Together these documents provide an insight into the grand feat of transporting the royal party across the country. What was most striking about these manuscripts, however, was not just the intricate level of details involved in the planning, but that these methodical scribbles in 1773 and 1788 were written in George III’s own hand. The King’s passion for detail and his fascination with mechanics, logistics, and indeed travel, have been noted by several scholars.[5] Nonetheless, for a monarch to take time to draw up detailed schedules for his trips, rather than bestow such menial tasks upon an equerry, highlights George III’s enthusiasm for planning and the pleasure he derived from his visits to counties across England.

GEO/MAIN/16319, Horses for a journey to Cheltenham, 1788

This monarchical involvement in planning was not just limited to transportation routes, George III was also personally invested in arranging his accommodation. The large volume of correspondence between the King and John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, in both 1773 and 1778, demonstrates the keen interest George III had in organising his visits by his planning meals, ordering furniture, and designating rooms for himself and his servants at the Commissioner’s House within the dockyard at Portsmouth.[6] By corresponding directly with his hosts, rather than via his courtiers, George III could guarantee that the arrangements were to his exact liking, and more importantly, ensured an enhanced level of privacy on the tour – a trait that would characterise his visits. Even at Weymouth – the town that George III is arguably most associated with, having visited fourteen times between 1789-1805 – the King travelled with a reduced court and set up a home-away-from-home at Gloucester Lodge on the seafront. By seldom residing with the aristocracy at their country estates, and instead holding a preference for renting smaller, vacated houses – much to the disgruntlement of some courtiers, including Fanny Burney as she vented in her diaries – George III was using travel as a form of escape from court duties and an opportunity to indulge in his private interests and family life.[7]

George IV’s Visits

As historiography as proved time and again, George IV and his father were in opposition to each other, and their contrasting styles of travel were just another example of this.[8] Either because of personal preference or because of this desire to deliberately strike out against George III, George IV embraced a very different approach to travel.

With a long tenure as Prince of Wales, and fewer responsibilities than the monarch, George IV had a greater freedom to travel, and indeed it seems that pleasure was at the heart of his journeys. Invitations to visit his noble friends’ country houses provided a reason to travel and to spend time in relative privacy away from the spotlight in London, Windsor, and Brighton. Like his father, George IV corresponded with his hosts to discuss residing with them. Where this correspondence differed, however, was that George IV appears to have had less interest in the logistical issues arising from his visits and was more concerned with the activities he would be engaging with. Letters from Mary Isabella, the Dowager Duchess of Rutland at Belvoir Castle near Grantham in December 1798 asked politely if the Prince would attend a ball she was throwing for the coming of age of her son, John Manners, 5th Duke of Rutland.[9] The party itself provided the opportunity for the Prince to visit other friends along the route, including Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira at Donington Hall in Leicestershire.[10] George IV’s style of travel mirrored that of the more traditional royal tour of the Tudor or Stuart period; taking longer to progress from one county to the next and residing at country houses at each stop. Such a tactic was not just a nod to a bygone era but allowed George IV to spend an increased time in private company with his aristocratic friends and indulge in his favourite pastimes.

There can be no grander examples of George IV’s pursuit of pleasure through travel, though, than his state visits to Dublin in 1821 and Edinburgh in 1822. These visits have attracted recent scholarly attention in terms of documenting the day-by-day activities of the King, and the displays of pageantry and national identity.[11] There is little evidence of George IV’s personal involvement in the planning of these two momentous visits, which instead appear to have been largely orchestrated between government officials and local corporations. Nonetheless, evidence in the Royal Archives does hint at George IV’s spending whilst on tour, and, in his typical fashion, no expense was spared. Receipts and account books reveal the level of expenditure as well as a few of the more expensive souvenirs George IV purchased on his travels: an £84 gold box ordered from Matthew West in Dublin appears to have been one of the King’s cheaper mementos from his travels.[12] Preceding his trip to Scotland in August 1822, the King was granted £5,000 ‘for private purposes, receiv’d from the Treasury’.[13] Although it is not specified what this vast sum was to be spent on in Scotland, there is one bill which stands apart for its lavishness and expense – that of George IV’s tartan outfit to transform him into a Highland Chieftain. The receipt from George Hunter & Co of Edinburgh, totalling £1354 18 shillings, included everything from Royal Tartan Plaid, to bejewelled gold broaches and buckles, Moroccan leather belts, goatskin purse, powder horn, Highland dirk, pistols, and basket hilt sword.[14] Attendees at the levées, drawing rooms, and balls agreed that the King cut a fine figure in his Highland dress, even if his ‘Buff coloured Trowsers like flesh to imitate His Royal Knees’ did cause a few eyebrows to be raised.[15] The full impact of the King dressed as one of his fellow Scotsmen was later manifested in Sir David Wilkies’ portrait, at a cost of 500 guineas, which now hangs in the Royal Dining Room at Holyrood Palace.[16]

RCIN 401206: Sir David Wilkie, George IV, oil on canvas, 1829

Comparison

The two kings provide a contrast in how royal visits of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were conducted, and how such visits reflected their distinct personalities. George III demonstrated a pragmatic approach to travel and revelled in the hands-on involvement in the mundane logistical issues; George IV viewed travel as a source of pleasure and to spend time with his close friends. With travel came an increased exposure of their image across Britain, and both monarchs had the difficult task of balancing their need for personal privacy with the need to be seen publicly to secure the monarchy’s position within society. George III took to this in a low-key style through his visibility walking through town centres unguarded and conversing with shopkeepers, farmers, and local inhabitants; George IV, in contrast, used the full pomp and ceremony of state visits to celebrate his arrival and unmissable presence in the town. The lens of royal visits allows for an alternative understanding of how the later Hanoverian monarchs gathered public support through the level of personal involvement and planning with which they engaged preceding royal visits, and the degree of publicity which they attracted when on tour.

Notes

[1] British Library, ‘King George III Topographical and Maritime Collections’, British Library (2021), https://www.bl.uk/collection-guides/king-george-iii [accessed 10 April 2021].

[2] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/16004: Memoranda concerning arrangements for a journey to Portsmouth, 12 June 1773.

[3] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/2946: Arrangements for a visit to Portsmouth, May 1778.

[4] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/16319: Horses for a journey to Cheltenham, 19 July 1788.

[5] Jeremy Black, The Hanoverians: The History of a Dynasty (London and New York: Hambledon and London, 2004), p.118; Jonathan Marsden, ‘Patronage and collecting’, in Jane Roberts (ed.), George III & Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste (London: Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd, 2004), p.162.

[6] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/1583: Lord Sandwich to George III, 7 June 1773; Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/1584: Lord Sandwich to George III, 7 June 1773; Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/1600: Lord Sandwich to George III, 14 June 1773. George III’s responses to Lord Sandwich’s letters are held at the Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich: SAN/F/45/C, 1771-1778.

[7] Frances Burney, Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, vol. 4, ed. Charlotte Barrett (London: Henry Colburn, 1854), p.133.

[8] G.M. Ditchfield, George III: An Essay in Monarchy (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), p.56; Black, The Hanoverians, p.153; Stella Tillyard, George IV: King in Waiting (London: Allen Lane, 2019), p.18.

[9] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/39537-8: Duchess of Rutland to Prince of Wales, 19 December 1798; Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/39539-4: Duchess of Rutland to Prince of Wales, 22 December 1798.

[10] London Chronicle, 3-5 January 1799.

[11] Deborah Clarke, ‘George IV’s Visits to Ireland, Hanover and Scotland’, in Kate Heard and Kathryn Jones (eds), George IV: Art and Spectacle (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2019), pp.215-223; John Prebble, The King’s Jaunt: George IV in Scotland, August 1822: ‘One and Twenty Daft Days’ (London: Collins, 1988).

[12] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/35642-35678: George IV Bill Book, Privy Purse, 1822-1827.

[13] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/32660: George IV to Robert Gray, 8 August 1822.

[14] Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/29600: George Hunter Bill, 23 September 1822.

[15] National Records of Scotland GD157/2548/3: Harriet Scott to Anne Scott, 17 August 1822.

[16] Royal Collection Trust RCIN 401206: Sir David Wilkie, George IV, oil on canvas, 1829.