Asian State letters now available on the Georgian Papers online

By Julie Crocker, senior archivist, Royal Archives

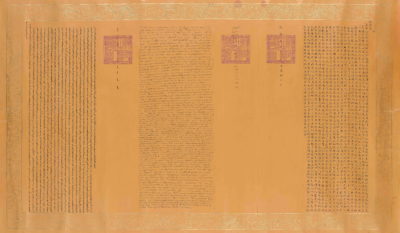

RA GEO/ADD/31/21/A: front: (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2022

A recent addition to Georgian Papers Online are the Asian State Letters held in the Royal Archives (reference GEO/ADD/31/1-22). This collection of letters and wrappers, mostly to George III and George IV from rulers of countries including China, India and the Ottoman Empire, is one of the most unusual and fascinating series of documents within the Georgian Papers.

The documents sent by the Chinese Emperor Ch’ien-Lung (Qianlong) to George III in 1793 (GEO/ADD/31/21a-d) are perhaps the most extraordinary items in this collection. The two letters, or edicts, and two lists of gifts, resulted from the Mission sent by George III to Emperor Ch’ien-Lung in 1793. The principal aims of the Mission, led by Lord Macartney, were to establish direct diplomatic relations between Britain and China by having a British Ambassador at the Chinese Court, and also to negotiate trading concessions and open up new markets for British merchants. The Mission travelled to China in ships laden with the very best British goods to present to the Emperor and letters from the King explaining his wishes.

Macartney arrived in China in August 1793 and was granted an audience with the Emperor, during which he presented the letters and gifts. In return he received the two edicts from the Chinese Emperor to take back to George III, together with many gifts. However, from a trade point of view, the Mission was a complete failure. The first edict (GEO/ADD/31/21a) contained the Emperor’s refusal to allow a British Ambassador at his Court under the usual diplomatic terms, while the second (GEO/ADD/31/21b) stated the Emperor’s refusal to agree to any of the trade concessions that the British had requested.

The first edict, shown here, measures over three feet by nearly six feet and is made of one enormous piece of gold-flecked eighteenth-century Chinese handmade paper, beautifully decorated with fine calligraphy. Originally it was encased in a bamboo cylinder, but this no longer survives. Interestingly, it was drafted on 3 August 1793, three days before Macartney’s arrival in China, so it seems the Emperor had decided to dismiss the Mission before it even arrived (not least because of Qing concern over British activities in the Indian Ocean world). This edict, like the second and the lists of presents, is written in three languages, Manchu, Latin and Mandarin Chinese, which helps to explain its significance. Hitherto the Chinese had generally zealously guarded their written language, with severe penalties for any Chinese found translating the written language for westerners. These documents, however, having been drafted in Mandarin Chinese, were then translated into Manchu and then into Latin by Jesuit missionaries in Peking. When Macartney returned to England with the documents, they provided fresh opportunities for Britons to translate and study written Manchu and Mandarin texts.

For more on the Macartney mission, see the series of recent publications by Henrietta Harrison, and her contribution to the Georgian Papers roundtable on Global Georgians: Transnational Interactions with the British Monarchy available here: https://georgianpapers.com/2021/06/29/global-georgians-transnational-interactions-with-the-british-monarchy/

See also :

The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

“The Power of the Interpreter in Intercultural Negotiations: Li Zibiao and the 1793 Macartney Embassy to China”, International History Review 5 (2019)。

“Chinese and British Diplomatic Gifts in the Macartney Embassy of 1793”, English Historical Review 133.560 (March 2018).

“The Qianlong Emperor’s Letter to George III and the Early Twentieth-Century Origins of Ideas about Traditional China’s Foreign Relations” American Historical Review 122.3 (2017).