“Long a Dispute Amongst Antiquarians”: How a King’s Understanding of History Changes our Understanding of a King (and History)

Nathaniel F. Holly, Ph.D. Candidate in History,

William & Mary

Jump to Transcription & Images

In what is surely one of the best examples of early modern clickbait, King George III laments the loss of Britain’s American possessions with what was must have been a tortured scream of anguish: “America is lost!” But what if that was a primal howl of relief instead? Part of what makes reading the voluminous essays of King George III so refreshing is his instinct to retreat to the safe confines of historical perspective to assuage his anxieties. For the King, other “Antiquarians” were simultaneously sources of frustration and solace. While he knew, for example, that historians had long argued about whether it was the Saxons or the Normans who introduced “Feudal Institutions,” he also knew that both sorts of arguments could be correct: “we may safely aver by both to explain this.” This proclivity for perspective also provides modern historians with plenty of provender for their own projects. While the King’s essays on governance and history—which ranges from a treatment of the “Original Nature of Government” to a “Short History of England”—offer quite a bit to consider about more traditional subjects like the law, property, and politics, they also contribute to our understanding of more far-flung topics. There is even material for those like me who study topics like transatlantic Indians. But before we flesh out the possibilities of the full collection (or at least the slice of it I am considering here), let us return to the essay that shouts the loudest.

For an essay that begins with an exclamation, the bulk of the “America is Lost” piece seems to either be a cowed post hoc rationalization of a colonial order gone awry or a reasoned assessment of a decidedly difficult situation. I vote for the latter. For King George III, it seems that questions of commerce were more pressing than questions of governance or political power. Rather than refer to the rebelling colonies by name, the King employed commodity labels—Sugar, Rice, and Northern (read North of Tobacco). As he concludes, “we shall reap more advantages from their trade as friends than ever we could derive from them as Colonies, for there is reason to suppose we actually gained more by them while in actual rebellion.” If we read that line and the more famous opening line together, King George III seems to be making a reasonable assessment. And if we place this most famous of essays in conversation with some of his other writings, a new sort of Monarch emerges. One who is both deeply concerned with historical questions and who offers historians of the early modern Atlantic world a wealth of opportunities for their own inquiries and analysis.

As you would expect, a monarch has more (much more) to say about governance. Yet the foundation for these beliefs on governance emerge from a particular understanding of history. For King George III history is a progression. Though the “first rudiment of the state” began as a “purely domestick” affair, eventually, “When many Familys came to reside it together it could not be long before some head…gain’d Authority over the rest.” The only logical conclusion to this process, of course, was either “Monarchy, or a Republic.” According to the King, “the world grew more civiliz’d & society more perfect & All History confirms the truth of these progressions.” Indeed, King George III draws a distinct line between the “Antient Britons” who lived like “Nomades in Tents, without Towns or Citys” and who subsisted on “Milk & roots” and more modern and “civiliz’d” peoples.

For my own research interests—southeastern American Indians—seeing this information confirmed in the handwriting of King George III allows for a more nuanced interpretation of early cross cultural encounters in the Americas. What does it mean that British officials frequently labeled indigenous leaders “Kings” instead of something less…progressive? What about the British Monarch’s meeting with indigenous peoples in the 1760s? Did he view his visitors as analogues of “tribal” Saxons? Or as something a bit more evolved? These papers offer the possibility of a perspective on those meetings that historians could have only wished for until recently. While I think King George III would lump me in with those Antiquarians who “have laid great stress” on the wrong sorts of questions, this small peek into his way of looking at the world could change things for all manner of scholars.

George III Essays Referenced:

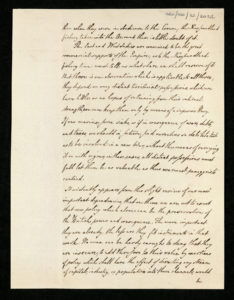

RA GEO/ADD/32/2010-2011, Essay on America and future colonial policy, [?1784]. Royal Archives, Windsor.

RA GEO/ADD/32/914-917 and RA GEO/ADD/32/957-995, Essay and draft essay on government, [1756-1780]. Royal Archives, Windsor.

RA GEO/ADD/32/1039, An Essay upon the Original and Nature of Government, [1746-1805]. Royal Archives, Windsor.

Transcription: America is Lost! (Essay on America and future colonial policy)

Transcription provided is the raw transcription, initial product of student transcribers. Text is not corrected nor proofed.

Download full raw transcription: RA GEO_ADD_32_2010_Raw Transcripton (pdf)