George IV (1762-1830) when Prince of Wales 1803, RCIN 400511. Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

By the end of his life in 1830, George IV would be known for his indulgent lifestyle, extravagant taste and manifold mistresses, but in 1779 he was just a sixteen year old boy who was powerfully infatuated with a lady of the court, Mary Hamilton, six years his senior.

Mary Hamilton was born in 1756 to Charles Hamilton (1721-1771), son of Lord Archibald Hamilton; and Mary Catherine (d.1778), daughter of Colonel Dufresne, aide-de-camp to Lord Archibald Hamilton. Growing up, Hamilton was educated, popular, and an avid correspondent. In 1777, she had been asked by Queen Charlotte to come to court in order to assist with the education of the younger princes and princesses.

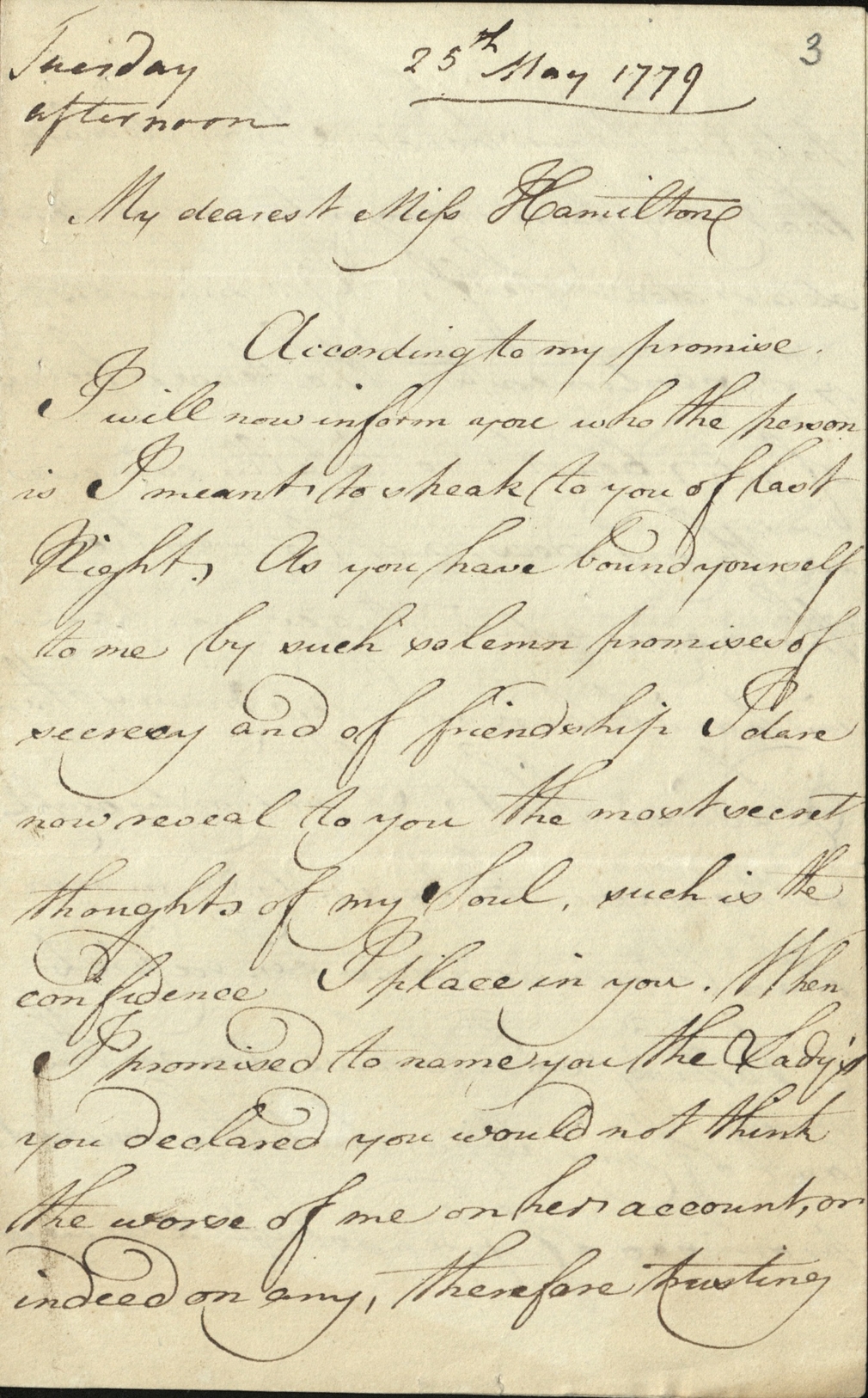

Writing on the 25 May 1779, the Prince promises to tell Hamilton his secret: the name of the lady who he is in love with, and reveals,

I now declare that my fair incognita is your dear dear dear Self…Your manners, your sentiments, the tender feelings of your heart, so totally coincide with my ideas, not to mention the many advantages you have in form & person over many other Ladies, that I not only highly esteem you, but even love you more than Words or ideas can express.

The correspondence which follows comprises 138 documents made up of the letters from the love-struck Prince, sent between April 1779 and December of that year, and her draft letters and notes to him.

At their heart, the Prince’s letters are love letters, and give a strong emotional insight into the character of George IV as a young man. However, they do not only contain expressions of emotion and secret rendezvous. These letters are remarkable because they can also give us an exciting insight into the lives and personalities of the Royal Family, and the day-to-day workings of the Court. They provide a contemporary snapshot of fashionable society, of fashion and the giving of gifts, of literature, sport, health and medicine.

Letter from George, Prince of Wales to Mary Hamilton, 25 May 1779, GEO/ADD/3/82/3 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

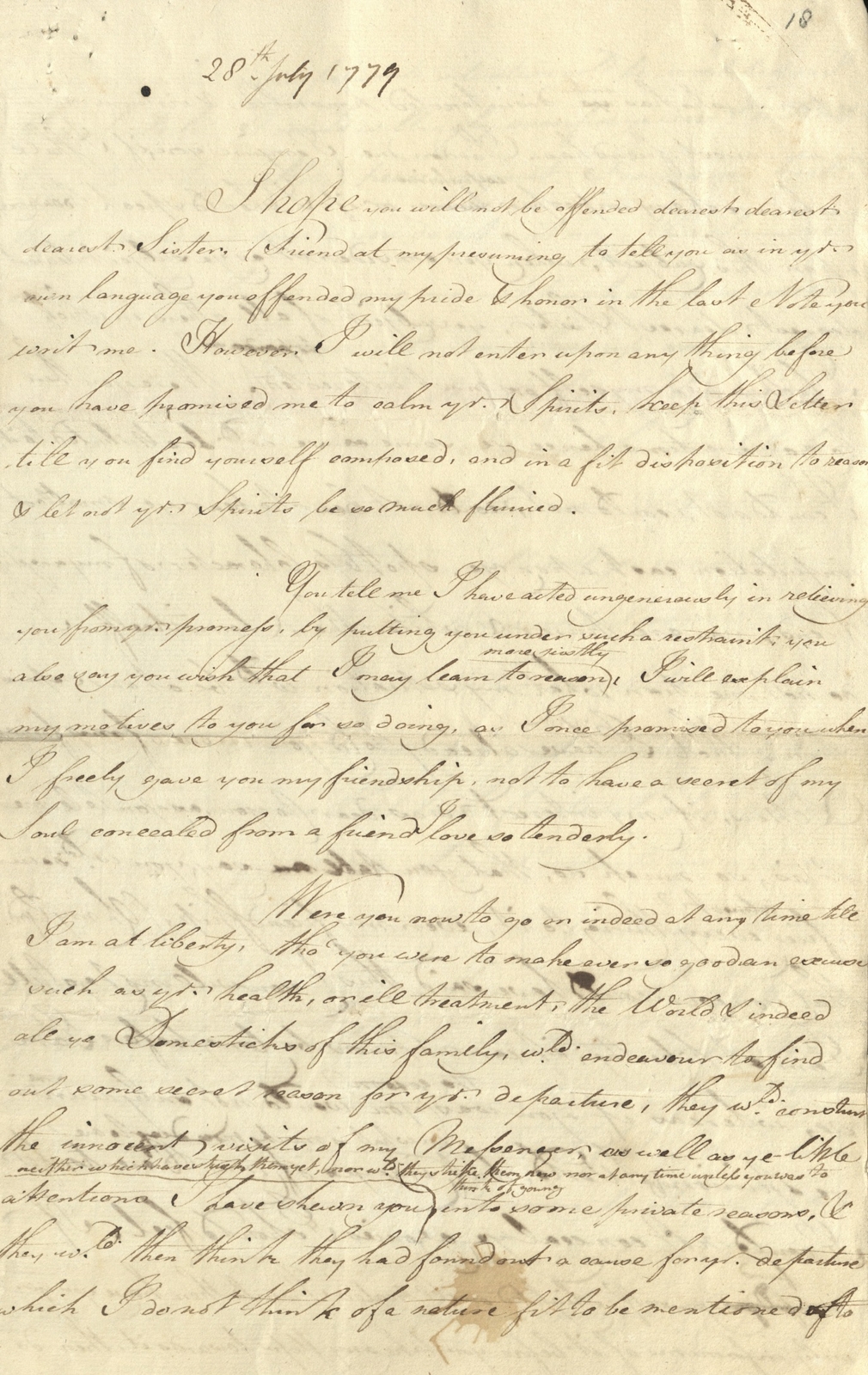

While the letters testify to the Prince’s clear infatuation with Hamilton, both parties emphasise the importance and sincerity of their friendship. To the Prince, Hamilton is ‘the only friend to whom I can communicate my most hidden & inward thoughts’. Hamilton herself, although she continues their correspondence, does not reciprocate his passions, but is a very critical and blunt correspondent, and does not shy away from condemning his character and actions. We hear in the Prince’s words of ‘the delicacy of [her] wit, & the sharpness of [her] irony’, calling her‘a little whimsical, odd, unaccountable, comical, romantick creature’, and a ‘madcap’ among her friends. She herself states that ‘I never will have a friendship with a person who would not be as happy or even feel as proud of my friendship as I was of theirs’. She is a reluctant rather than a flattering courtier, and this position gives us an interesting window into daily life and the Prince’s character.

Hamilton frequently criticises the Prince’s conduct, from his swearing – ‘that vile vulgar shocking vice’ – to his horse riding, and counsels him ‘not to adopt the follies of others’. She remarks on his ‘uncommon share of animal spirits, & an inherent turn to ridicule’, and how it provokes her to ‘see [him] so often & repeatedly in the papers as a Hero of some ridiculous adventure, or silly letter from a Brighelmstone Miss’. The Prince states, in a now ominously ironic way, that ‘you tell me you are dreadfully afraid for me if i should attach myself to every woman I like with the same impetuosity I have to you, call not that impetuosity, call it constance…’

The Prince’s early love of fashion is evident in the collection. He sends Hamilton patterns and colours to choose from, discussing the ‘tabinet’ coat with a white ermine lining that he wishes to have made up for New Year’s Day. His shoes and buckles are described as ‘remarkably tight & large’, and we hear an amusing anecdote that Hamilton had heard from an acquaintance, which she reports back to the Prince, relating to his obstinacy in wearing such clownish shoes:

[The] King took the Prince a remarkable long walk through Bogs, up Hills, over stones etc. the Prince’s shoes burst at the sides & what with the weight of the buckles & the tightness of the shoes and the length of the walk his feet were covered with blisters, & he was quite lame- the King flattered himself he had gained his point, but the prince’s obstinacy was proof against his sufferings, & he appeared at Dinner, & ever since in tight shoes & large Buckles…

Their correspondence also sheds light on the characters of George III and Queen Charlotte. In July 1779, the Prince writes that

…it is true that my dearest father loves a joke.. and tho perhaps his irony may not be of so delicate a nature as my own, yet he never means any harm to the person against whom he employs it, tho it may appear as if he did; I am sure he never can mean any to you, the bent of all his jokes is to make you laugh to that excess which he delights in.

Regarding Queen Charlotte, the Prince writes that ‘I have long seen, & perceived with regret, the little sensibility of tenderness in the disposition of my [mother]’, and Hamilton reflects on the ‘peculiar misfortune’ of being ‘placed in a sphere where it becomes necessary to hide & even stifle if possible the delicate feelings of the heart’.

Letter from Mary Hamilton to the Prince of Wales, 23 October 1779, GEO/ADD/3/83/18 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

As the correspondence moves into December we hear of the Prince’s plans to go to the theatre. On the 5 December 1779 he writes to Hamilton that whilst there he has seen,

the most beautiful woman, that, ever I beheld, who acted with such delicacy that she drew tears from my eyes, she perceived how much my attention was taken up with her, not only during her acting but when she was behind the scenes, & continued every little innocent art to captivate a heart but too susceptible of receiving every impression she attempted to give it, & alas my miranda, my friend, she did but too well succeed… her name is Robinson…

This was the beginning of the Prince’s relationship with the actress Mary Robinson, who would become the Prince’s first mistress. After this time, the correspondence between the Prince and Hamilton draws to a close.

After wishing to leave for some time due to the exhausting demands of life as a courtier, Hamilton was finally permitted by Queen Charlotte to retire from court in 1782. In 1783 she moved to London and lived as part of the ‘bluestocking’ circle, continuing her friendships with intellectual figures such as Frances Burney, Mary Delany, and Elizabeth Carter. In 1785 she married John Dickenson with whom she had one daughter, Louisa, born in 1787.

Mary Hamilton’s papers were kept and arranged by her descendants, with selected extracts published by her great-grandchildren Elizabeth and Florence Anson in 1925, in Mary Hamilton, Afterwards Mrs John Dickenson, At Court and at Home From Letters and Diaries 1756-1816. The correspondence between Hamilton and the Prince of Wales was purchased by The Royal Archives in 2006. Further papers of Mary Hamilton, including her diaries, extensive correspondence, and commonplace books, are held at the John Rylands Library at The University of Manchester.