George IV (1762-1830) when Prince of Wales September 1782, Thomas Gainsborough. RCIN 401009 ©

The official correspondence of George IV as Prince of Wales between 1766 and 1805 is now digitised, catalogued, and available online.

As Prince of Wales, George IV lacked an official role and occupation. This was something he resented throughout his life, in particular his father’s refusal to allow him to follow a meaningful military career. In 1795, at the age of 33, he wrote to his father.

At a stage of life which calls upon others to incline themselves to serious pursuits, I find myself barred from the objects of application natural & becoming to my rank. The chain of public affairs, whence I might have derived instruction as well as occupation, has been uniformly withheld from me…

This means that the division of ‘official’ and ‘private’ is quite an artificial distinction when considering George IV’s papers; and the two should be considered in tandem. This will be possible when George IV’s private correspondence is published at a later stage of the project. However, while clear distinctions cannot be drawn between the two, the official correspondence highlights the prince’s political, financial, and military interests, and questions of patronage. These papers allow us a window into the spheres that the Prince operated in and how he conducted his business, shedding light on his involvement in the political world, in support of the Whig party against his father’s administration, and his well-known financial difficulties.

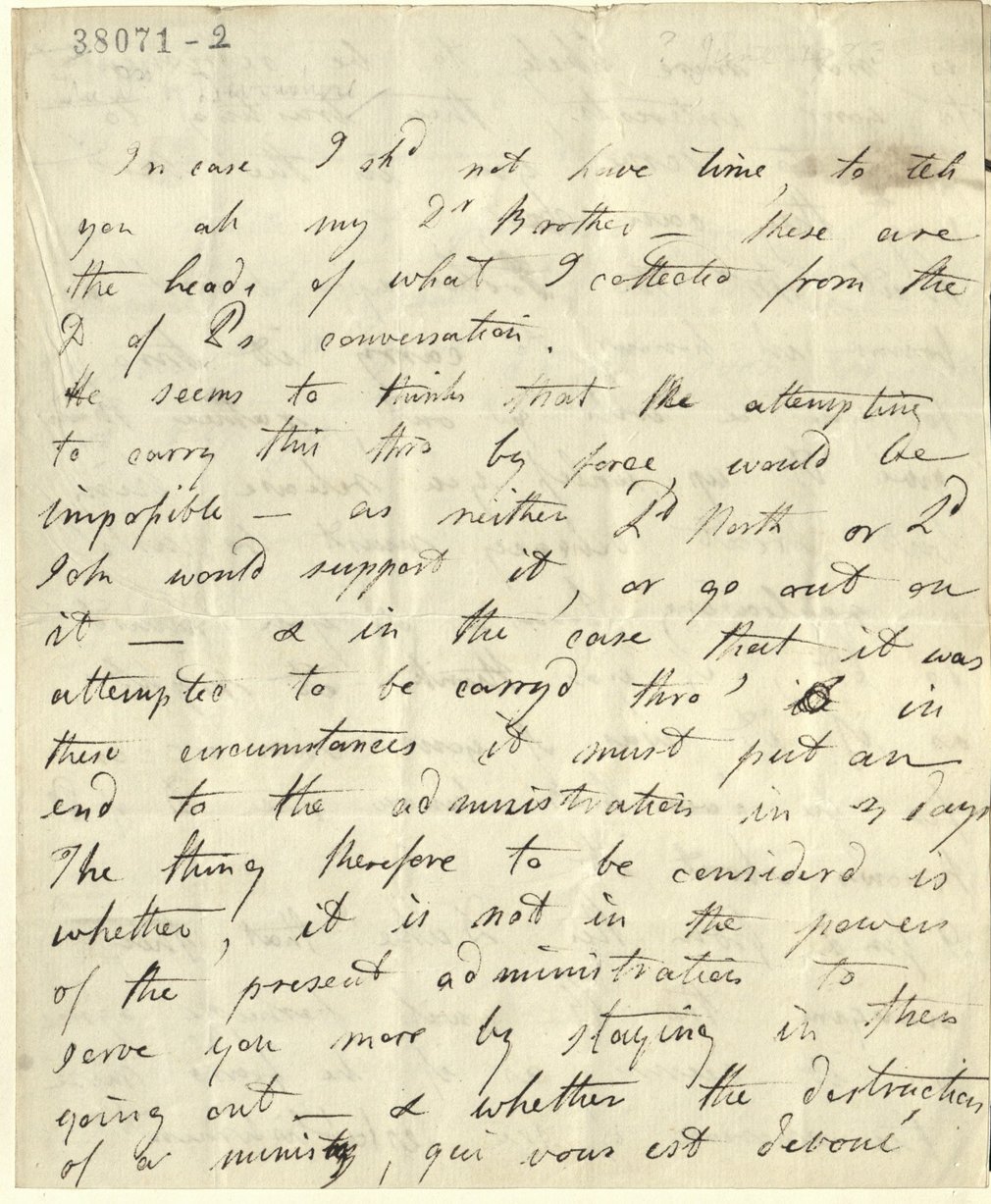

Letter from the Duchess of Devonshire to George, Prince of Wales, 1783, GEO/MAIN/38071-38072 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Many letters relate, unsurprisingly, to the debts amassed by the Prince, and his appeals for parliamentary assistance. A large factor in this debt was the costly refurbishment of his residence Carlton House, compounded by his (as he viewed it) unfairly restrictive allowance. In July 1786 he dismissed a large proportion of his household, showing his determination to live as a ‘private gentleman’, in a theatrical demonstration of his financial hardships. In 1792 letters reveal the very real risk of furniture being seized from Carlton House if the financial relief of his tradespeople was not instantly arranged. There are also papers relating to loan procurements from ‘Antwerp bankers’, the Landgrave of Hesse Cassel, and transactions with banks including Coutts & Farrer, Sir Walter Stirling & Co, and Hammersley’s, which could shed light on the operation of finance in this period.

The Prince’s appeals for parliamentary assistance with his finances were by necessity political. The Prince was both a unifying cause , allowing his Whig allies to challenge the King’s administration under William Pitt, and at times a source of risk or even embarrassment to them. A letter in June 1783 to the Prince from the influential Whig the Duchess of Devonshire, seeks to make the Prince realise that keeping Charles James Fox bound to his commitment to support a measure to relieve his debts would likely cause the administration to collapse, and it would be in the Prince’s best interest for the Whig government under the Duke of Portland to remain in power.

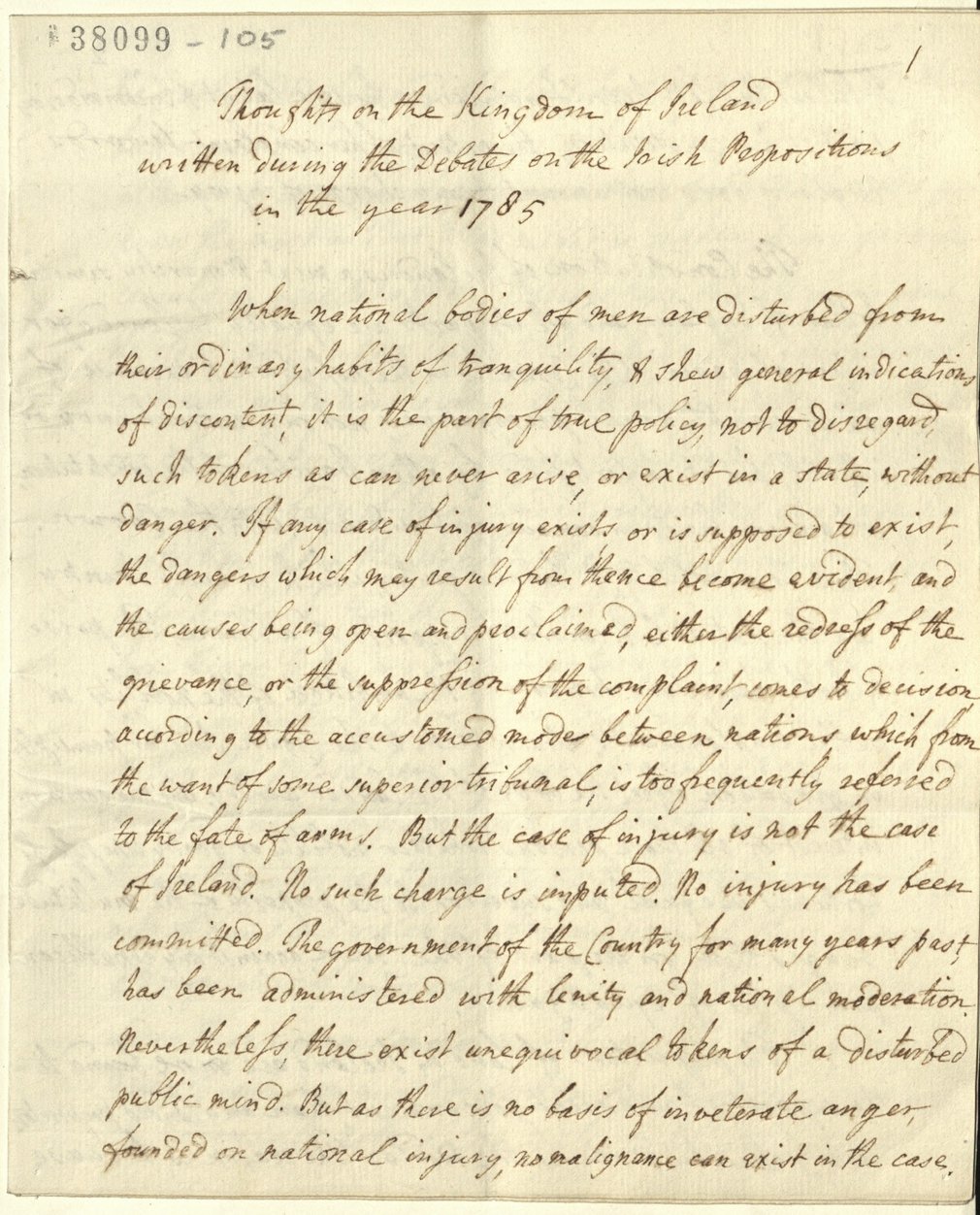

Memorandum on Ireland regarding its history and Constitution, and the possibility of George, Prince of Wales, being crowned King of Ireland, 1785. GEO/MAIN/38099-38105 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Interestingly, the papers also show evidence of the Prince’s connection to Irish politics. Included in the papers is an (GEO/MAIN/38099-38105) anonymous memorandum dating from 1785 proposing the creation of an Irish Crown with George, Prince of Wales, crowned King of Ireland. As sovereign, the Prince ‘would repeople the country with nobility, gentry and yeomanry; it wd inspire new life into the peasantry’ and bring about prosperity and stability in Ireland. During the turmoil of the 1788-9 Regency Crisis, in February 1789, the Irish Parliament gave an Address to the Prince offering him the unrestricted regency of Ireland, going against the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and British Government. This, however, coincided with the King’s recovery, and the prospect of any regency was dismissed. As might be said about the Prince’s role within the Whig party; for those seeking reform in Ireland, rallying around the disaffected Prince allowed them to oppose the government without appearing disloyal to the Crown.

Ireland continued to be a key political issue in this period, and during the 1790s the Prince was supportive of Catholic emancipation, and spoke against the restrictive measures undertaken by the Administration. In this he was likely influenced by his close friend and advisor Lord Moira, and extensive correspondence with him is included within these papers. In a memorandum written in 1797, which was snubbed by William Pitt and his government, the Prince discusses the strength of the United Irishmen, and proposes that he himself undertake the government of Ireland. These papers provide a rich resource for further research into the Prince’s connection with Ireland.

As well as unrest in Ireland, this turbulent period included the American Revolution, the French Revolution and the Revolutionary Wars which stretched from 1792 to 1802. With the Prince’s attempts to join in the action repeatedly frustrated, the papers show us how he received military and political information from a variety of sources. This included letters from his brother Frederick, Duke of York, reporting from the Siege of Valenciennes in 1793; and from Lord Cornwallis, Governor-General of India, reporting on the war with Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore.

The French Revolution fascinated the Prince, who in a letter of 1792 to Queen Charlotte writes that ‘it must have some connexion with French politicks to be interesting at all at this moment‘. The unsettled political climate of Europe, with French invasion seen as an immediate threat, seems to have solidified the Prince’s frustration at being denied a military career. The Prince had been made Colonel Commandant of the 10th Regiment of Dragoons, but all his attempts at seeking promotion were rejected by George III. The correspondence reveals that this was a consistent source of tension, and many letters and drafts survive which show his desperate efforts to get the King to change his mind.

In April 1795, the King attempted to focus the Prince’s ambitions on more domestic matters, expressing his hope that the character of the Prince’s future bride would ‘prove so pleasing to you that your mind may be engrossed with domestic felicity, which may establish in you that composure of mind perhaps the most essential qualification in the station you are born to fill, and that a numerous progeny may be the result of this union’.

Caroline of Brunswick when Princess of Wales 1795-96 Gainsborough Dupont, RCIN RCIN 404550 ©

In 1795, influenced by the need for financial assistance for his debts, the Prince married his cousin, the protestant Princess Caroline of Brunswick. Despite the King’s optimistic hopes, this relationship was a catastrophic failure, apart from the birth of a legitimate heir Princess Charlotte in 1796. The letters between the Prince and new Princess of Wales, members of the household such as Lord and Lady Cholmondeley, and their letters to George III and Queen Charlotte, show the deteriorating relations as the Princess fought to remove the Prince’s mistress Lady Jersey from her household.

The official correspondence of George IV as Prince of Wales provides an exciting insight into his spheres of interest and influence. They allow us a glimpse of the Prince’s personality and temperament, how he reacted to events and tensions, and how his family and advisors responded to him. The papers show the concern of the Prince over what people thought of him, and how his advisors warned him of the likely perceptions of his actions by the press and public. These fears came to ahead with the Regency Crisis and with the disastrous marriage to Princess Caroline.

Overall, these papers contain a vast amount of themes and events, and will be of value to those interested in the reign of George IV, his relationship with George III and the wider Royal Family, but crucially also for those interested in a wider context and perspective on the reign of George III, and the dramatic political events of the late eighteenth century.