George II by Christian Friedrich Zincke, RCIN 421796 ©

The papers of George II can be roughly divided into four parts:

Official papers

Although the State Papers of George II are held at The National Archives, a limited number of documents relating to George II’s official role as heir to the throne and later, as Sovereign, can be found among the Georgian Papers. These records have been grouped thematically into papers and correspondence concerning foreign royalty; documents on a proposed Regency should George II die before his grandson, the future George III, come of age; along with other, more miscellaneous papers, of an official nature, for example this copy of a letter from William Ansah Sessaracoa to Lord Halifax concerning trading relations in Ghana.

Typically perceived as a warlike monarch, it is unsurprising that army and military papers feature strongly among the papers of George II, reflecting the unrest and threats abroad. These include surprisingly affectionate letters providing advice and comfort to his favourite son William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, during the Seven Years’ War (GEO/MAIN/52967 and GEO/MAIN/52970) along with lists of French troops on the borders of the Netherlands and Alsace in 1742 (GEO/MAIN/52836). Papers relating to the military and civil establishment at the start and end of the reign of George I can also be found here (EB/EB/49 and GEO/MAIN/52751-52759 respectively). It seems likely that these were collected and used for reference purposes by George II.

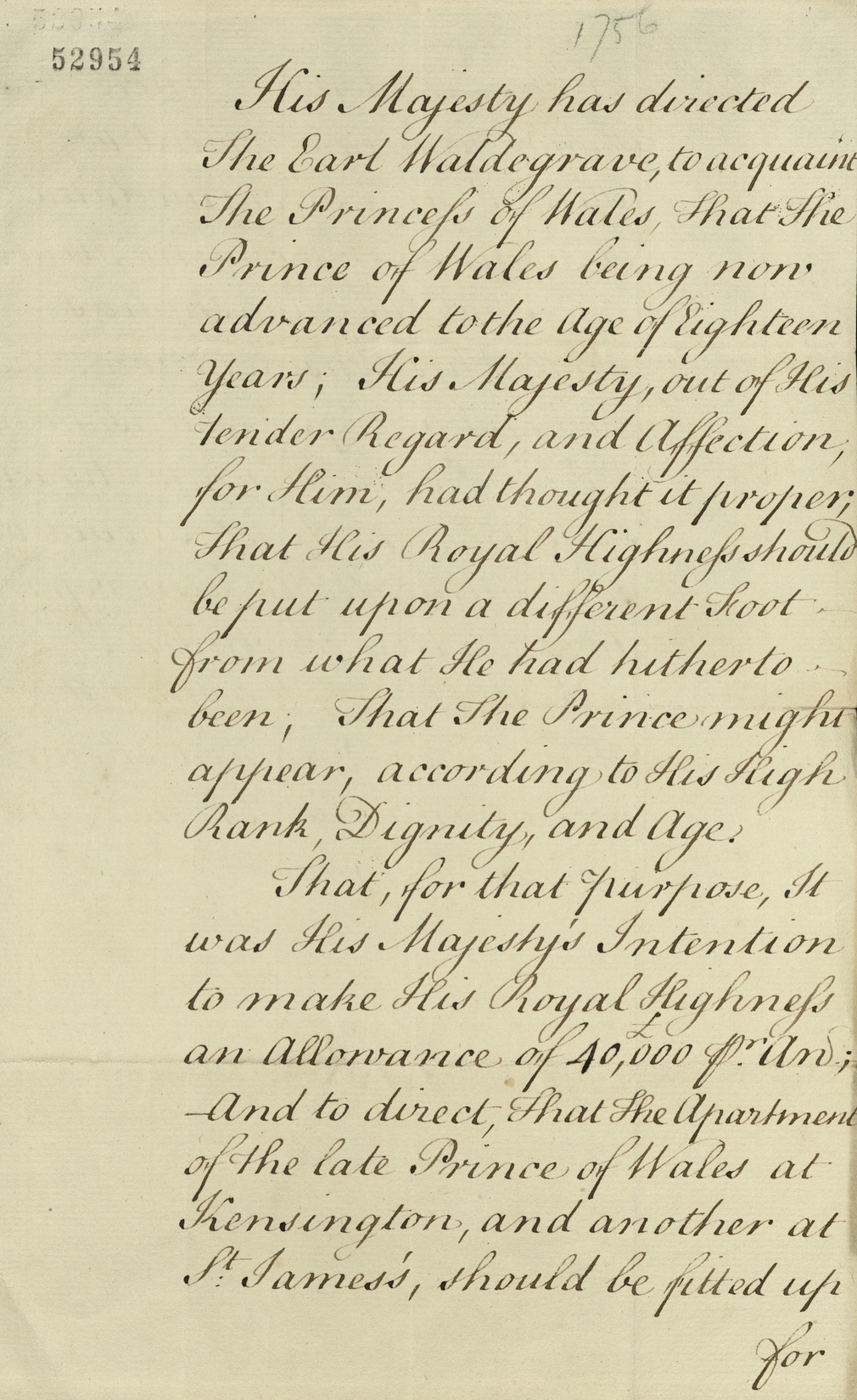

Offer by George II of £40,000 for the Prince and his brother Edward to be set up in their own households, 1756, GEO/MAIN/52954 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Private papers

Here private papers may be broadly defined as non-official papers, rather than documents conveying the innermost thinking and feelings of George II. Most touchingly personal, however, are the letters between George, Prince of Wales, his mother Augusta and his grandfather, George II. Following an offer by George II of £40,000 for the Prince and his brother, Edward, to be set up in their own Households, the heir to the throne instead refuses:

I hope that I shall not be thoughts wanting in the Duty I owe Your Majesty, if I humbly continue to entreat Your Majesty’s permission to remain with the Princess my Mother; this point is of too great consequence to my happiness for me not to wish ardently Your Majesty’s favour & indulgence in it.

Somewhat surprisingly this indulgence was granted and the 18-year-old prince remained with his widowed mother. Aside from the essays, there are comparatively few papers from George III as a young man and this affords us a fascinating glimpse into the life of the future monarch.

On a far more delicate and inflammatory matter is the copy correspondence between George II and his son Frederick, Prince of Wales found in the Additional Papers. Their subject is the conduct of the Prince of Wales at the time of the birth of his daughter, Augusta. Wishing to prevent his mother from being present at the birth, in the dead of night Frederick spirited his heavily pregnant wife away to St James’s Palace, some 15 miles away. George II was incensed:

This extravagant, and undutiful Behaviour in so essential a Point, as the Birth of an Heir to My Crown, is such an Evidence of Your premeditated Defiance of Me, and Such a Contempt of my Authority, and of the natural Right, belonging to Your Parents, as cannot be excused by the pretended Innocence of Your Intentions, nor palliated, or disguised by specious Words only.

An all-time low in their relationship, George II barred his son and family from his Court and residence at Hampton Court Palace. Orders prohibiting the admission to the presence of George II and Queen Caroline and to the Royal Palaces by those who have paid Court to the Prince and Princess of Wales can be found in the archive.

Establishment and financial papers

The hierarchical nature of court can be best seen among the papers relating to the management of George II’s Household. An establishment book (also GEO/ADD/1/49) set out the rank, salary and position of every member of the Household, from the Chancellor to the grooms and ‘necessary women’. The Household account books diligently record allowances for food, firing and lighting for each rank, while papers relating to Household furnishings including bills, estimates, receipts and warrants for payments for items such as plate and linen can be found in the Additional papers. Although many of the Establishment books have been previously available on FindMyPast, this tranche of records provide a greater range of information on those serving the king and his family. Receipts and orders to pay named individuals for services, such as the goldsmith John Tysoe, show the nature and operation of financial transactions.

Following the ‘Glorious Revolution’, the monarch received a grant from Parliament – known as the Civil List – to pay personal expenses and those of civil government; the Exchequer was to pay the expenses of the State. The Royal Archives holds Civil List account books and also papers which enable greater comparisons between the income and expenditure of George II and previous monarchs. During the reign of George III, the system would change again, however, many of the costs of civil government no longer the responsibility of the sovereign.

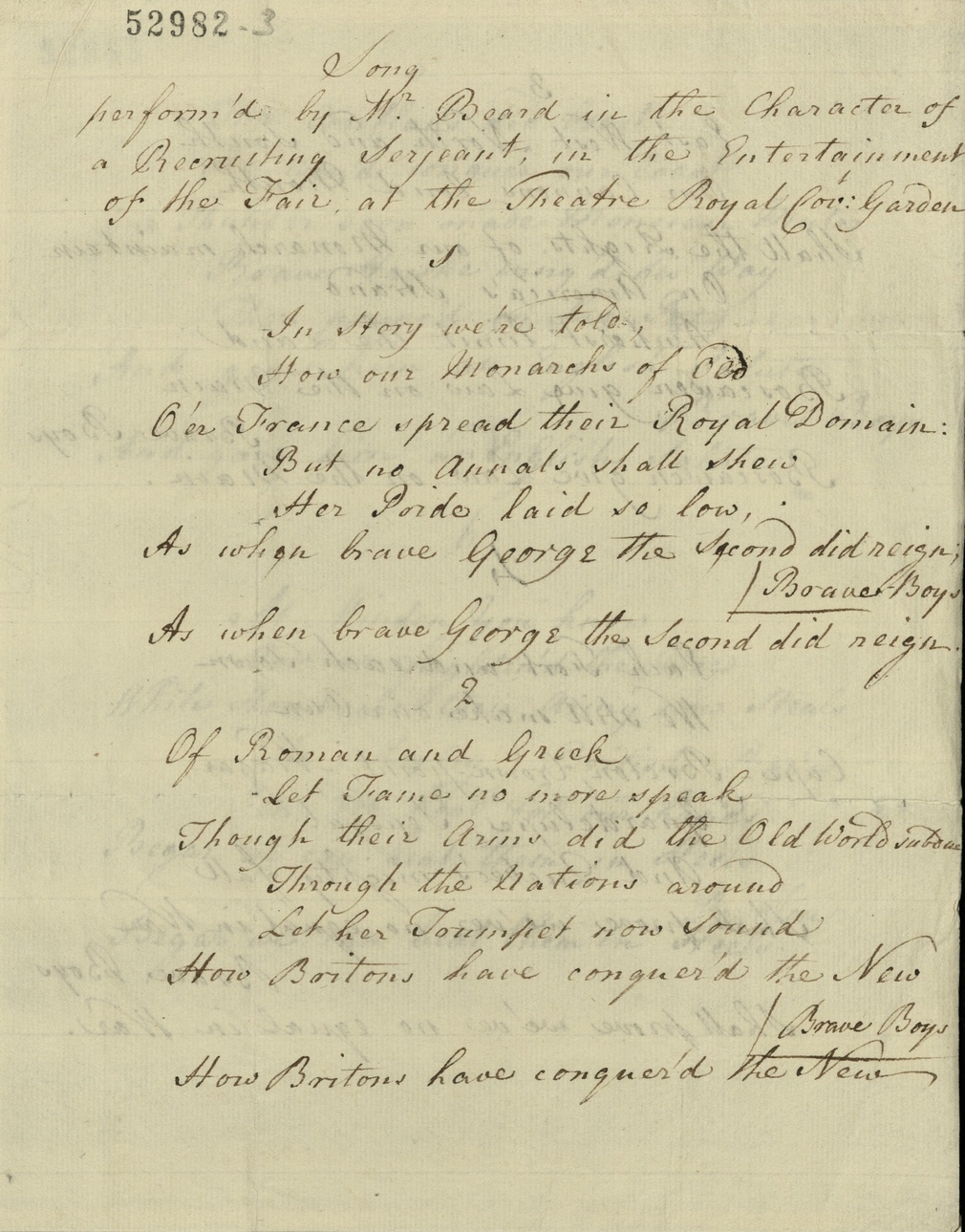

‘Song perform’d by Mr Beard in the Character of a Recruiting Serjeant, in the Entertainment of the Fair, at the Theatre Royal Covt Garden’, GEO/MAIN/52982-3 *Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Miscellaneous

These papers are not believed to have any direct link with George II other than dating from the time of his reign. These include documents such as a letter from Mrs Mary Selwyn, Woman of the Bedchamber, to Mrs Hannah Lowther on the last illness and death of George II’s beloved wife, Caroline; a letter from Stephen Poyntz to his former pupil William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland on the nature of God and mankind; and ‘Song perform’d by Mr Beard in the Character of a Recruiting Serjeant, in the Entertainment of the Fair, at the Theatre Royal Covt Garden’.