The papers of Princess Charlotte of Wales are a modest collection principally comprised of letters to, from and concerning the Princess, tracing the events of her short life from birth to the tragic aftermath of her untimely death during childbirth. In addition to correspondence this collection features two account books detailing Princess Charlotte’s establishment expenses for the years 1800 to 1805, as well as her poetry and prayer books.

Born at Carlton House on 7 January 1796, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales was the only child of the ill-fated marriage between George, Prince of Wales (later George IV) and Caroline of Brunswick. As the sole legitimate grandchild of George III, she became heir presumptive to the British throne at birth, and interestingly George III wrote shortly after her arrival stating that he ‘always wished it should be of that sex’. This does not however signify the King’s desire for a future queen, as he disclosed his hopes that the Princess’s birth would serve as ‘a bond of additional union’ and reconciliation between her parents, presumably leading to the birth of a male heir. This wish would never be realised as the Prince and Princess of Wales unofficially separated shortly after. The Prince, resolved that his wife should not be involved in decisions regarding the care of their daughter, took guardianship of Princess Charlotte in conjunction with the monarch.

The care of Princess Charlotte was prudently considered but the Prince of Wales relied heavily upon the advice of his mother, Queen Charlotte. In one letter to the Queen in 1796, the Prince of Wales wrote ‘Your choice & your opinion will ever guide mine, & I am so delighted indeed at the account you give me of Miss [Frances] Garth [for the position of Sub-Governess]’. In addition to Miss Garth the care of Princess Charlotte would be undertaken by a number of governesses and attendants including: Lady Dashwood, Alicia Campbell, Ellis Cornelia Knight, Lady Elgin, Lady de Clifford, Martha Udney, and the Duchess of Leeds, all of whom feature prominently within this collection as both correspondents and subjects.

Princess Charlotte of Wales as a child by Sir Thomas Lawrence, c.1801-1806 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

The Princess initially lived at Carlton House with her father (and mother who primarily resided there until 1798), but moved with her own modest household to Shrewsbury House, Shooter’s Hill, in 1799 and then in 1805 to Lower Lodge, Windsor, with the remainder of her time spent at Warwick House. It was at this time her formal education began in earnest, taking the form of a strictly regimented routine which, as befitting a future queen, was rigorous in comparison to most girls. Her lessons included history, French, English, Latin and religious instruction accompanied by dancing and music, with time allowed for other amusements and horse riding. Her education was not solely provided by governesses, but also by her preceptor (or teacher) John Fisher, Bishop of Exeter (later Bishop of Salisbury), and sub-preceptors. The Princess was not a natural scholar (with poor spelling and handwriting), but was a bright girl who showed an interest in law and politics (integral for her future as queen). This is demonstrated in 1811, when she asked for a copy of her father’s parliamentary speech regarding the resolutions and regulations of a Regency, as ‘it is a subject very interesting to all particularly so to me’ . She also admired poetry and compiled a book of extracts featuring the works of Thomas Milton and Alexander Pope, alongside the poetic letters of Lord Erskine.

The young Princess’s relationships with those within her household could be wrought with difficulty, particularly as she was known for her unusually informal manner and hot temper. This informal nature caused overfamiliarity with her sub-preceptor, George Frederick Nott, referring to herself as his adopted daughter and when he featured prominently in the ten year old princess’s will, he was accused of manipulating his charge. This document also demonstrates her contempt for Mrs. Udney to whom ‘for reasons’ she left nothing. Evidence of her temperament can also be found in Lady Elgin’s memorandum concerning the confiscation of a watch, writing that ‘the fire was kindled-The storm was violent- [the Princess] declaring her poor governess very cruel’.

Letter from Princess Charlotte of Wales to her father, the Prince Regent, in 1813. GEO/MAIN/49782 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

The Princess’s strong emotions are not only seen within her household relationships but in her intense friendships. She shared a lifelong bond with Priscilla Wellesley Pole (later styled Lady Burghursh) whose correspondence with the Princess (between 1813-1817) is included within this collection. She also had a close confidante in Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, to whom she entrusted with her most private affairs.

In addition to illustrating the Princess’s relationships with friends and her household her correspondence reveals her family connections. She regularly saw her extended family (George III, Queen Charlotte and her unmarried aunts) and the letters which passed between Princess Charlotte and her father provide a particularly fascinating glimpse into their complex relationship (and should be considered in conjunction with George IV’s own papers). Princess Charlotte evidently wished to please her father and often wrote to seek his approval and forgiveness. The Prince’s letters to his daughter demonstrate the infrequency with which he visited, yet this is not necessarily a sign of indifference, as he doted upon the young princess and his apologies were frequently accompanied by tokens of his affection. After the separation of her parents Princess Charlotte enjoyed regular visits with her mother, but due to the Princess of Wales’ indiscreet and scandalous behaviour contact became increasingly restricted. Princess Charlotte strove to obey her father’s wishes and often requested permission to write to or see her mother, and even informed him immediately after an accidental meeting with her mother in a park to avoid accusations of duplicity. However, despite rumours and unfavourable opinions of her mother Princess Charlotte remained steadfastly loyal until she began to question Princess Caroline’s motives in the aftermath of her clandestine relationship with Captain Charles Hesse. There are few letters between mother and daughter within this collection, but in one written in October 1817 Princess Charlotte candidly reveals her feelings towards the Princess of Wales upon her own impending motherhood.

Copy letter from Princess Charlotte of Wales to William, Hereditary Prince of Orange. GEO/ADD/22/12 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

The romantic life of the Princess Charlotte, although short, was eventful. From 1811 to 1813 she formed an attachment to Captain Charles Hesse of the 18th Light Dragoons, a relationship encouraged by the Princess of Wales who passed elicit correspondence and left them indecorously alone together. With Hesse’s departure for the continent the relationship came to an end but as Hesse had retained her letters it was still a threat to her reputation. This caused the princess much distress and to ensure the letters return she enlisted the help of Margaret Mercer Elphinstone who wrote extensively to Hesse between 1813 and 1814. Hesse’s co-operation was not forthcoming and rather than return the documents he promised their return upon his death, stating that some were safe in a chest with a friend who had instructions to send it ‘unopened to the bottom of the Thames’ if he was killed in battle, and the rest were on his person, a reply which unsurprisingly did not satisfy the recipient. Princess Charlotte eventually confessed the relationship to her father in December 1814 and disclosed she was left confused as to whether Hesse had been her admirer or her mother’s. In addition to Captain Hesse the Princess was linked to several others such as Prince William Frederick of Gloucester and an unknown man, thought to be Prince Augustus or Frederick of Prussia. However, as future queen she was expected to marry high ranking foreign royalty and in 1813 her father (then Prince Regent) deemed William, Hereditary Prince of Orange a suitable match. A meeting between the couple was arranged for December 1814, but far from being enamoured by the Hereditary Prince, the Princess was pressured into accepting an engagement. A letterbook of copy correspondence, principally between Princess Charlotte and the Hereditary Prince of Orange during 1814, reveals the emotions and events surrounding the proposed marriage. A crucial issue, creating extensive correspondence between the two kingdoms (and which the princess arguably hoped would end the match), was where the couple would reside. Princess Charlotte was adamant she would not leave her country despite her intended’s position as heir to the Dutch throne, but eventually she accepted a clause in her marriage treaty allowing her to remain in the United Kingdom unless she and her father agreed to her going abroad. Yet, this did little to change her feelings regarding the match and unable to alter her father’s mind and, facing being sent to the remote Cranbourne Lodge in Windsor for the remainder of her engagement, fled to her mother’s house in protest. Her stunt resulted in public sympathy and she decided to break off the engagement in a letter to the Hereditary Prince in June 1814. The Prince Regent was dismayed by the termination of the agreement, but he eventually accepted his daughter’s ‘strong, & fixed aversion to a match with a man for whom I can never feel…regard…necessary in a matrimonial connection’.

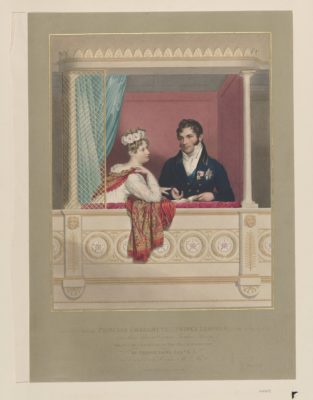

Princess Charlotte of Wales and Prince Leopold of Saxe Coburg, 1818 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

At the close of 1815, the engagement to the Hereditary Prince of Orange at an end, Princess Charlotte presented another candidate for her hand to the Prince Regent, declaring her ‘favour of the Prince [Leopold of Saxe-] Coburg [-Staalfeld]’ whom she had met in 1814. The Prince Regent, after meeting Prince Leopold in February 1816, granted his daughter’s wish and the Prince and Princess wed at Carlton House on 2 May 1816. The popular couple resided at Camelford House, moving the following August to Claremont in Surrey. Their union proved fruitful with Princess Charlotte becoming pregnant in early 1817. During her pregnancy the Princess sat for several well-known portraits, including one celebrating her receipt of the chivalric Order of St. Catherine. This honour was bestowed by the Empress of Russia the same year, and this collection features the Princess’s letter of thanks to the Empress.

When the Princess’s labour began, on 3 November 1817, she was significantly overdue and a long and difficult delivery resulted in the birth of a still-born son two days later. After the birth Princess Charlotte initially appeared to recover, but due to complications she died five hours later in the early hours of 6 November. Her care was overseen by her medical attendants Dr. Matthew Baillie, Sir Richard Croft, and Dr. John Sims, and witnessed by Privy Councillors (to authenticate the royal birth), and it is their reports and correspondence which detail the confusion and uncertainty surrounding the labour. The public, shocked by the tragedy, placed the blame for the Princess’s untimely death on Croft and his decision to forgo the use of forceps to assist the birth (a potentially lethal instrument at the time, used only in the direst of situations). Croft, blaming himself for the Princess’s death despite the Prince Regent’s assurance of faith in his decision, took his own life a few months later resulting in a ‘triple obstetric tragedy’.

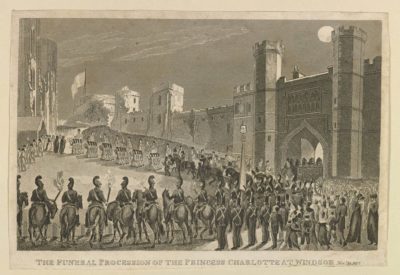

The Funeral Procession of the Princess Charlotte at Windsor, 19 November 1817 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Princess Charlotte’s untimely death deeply affected her family. Prince Leopold was distraught, and the Princess of Wales (who, living on the continent, had not seen her daughter since 1814) reportedly fainted upon hearing the news. Queen Charlotte wrote to the Prince Regent on 7 November stating ‘How painful it is for me to take up my pen at this moment when I had flattered myself to make use of it by giving you joy which it has pleased the almighty to turn to grief a mourning for us all’. The Prince Regent was so grief stricken that he was unable to attend his daughter’s funeral on 19 November at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, where she is interred alongside her son. The sudden loss of the popular Princess impacted the entire nation causing places of public entertainment to close out of respect, and on the day of her funeral mourners lined the streets of Windsor. The monument marking her tomb in St. George’s Chapel, created by the sculptor Matthew Coates Wyatt, was funded by public subscription and is a lasting testament to the popularity of the beloved princess who would have been queen.