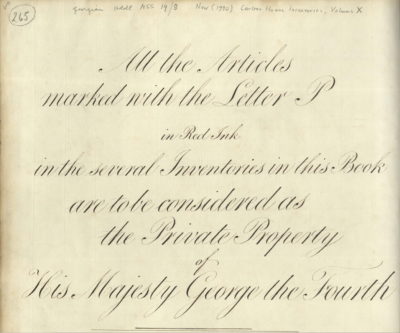

Figure 1. Inventory of the Private Property of George IV: GEO/ADD/MSS/19/8, p. i. Image Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty the Queen 2021. To see a high-definition reproduction, click the image. To read the catalogue entry, click here.

The inventories enable us to explore the complex relationship of property and the crown.

The intriguingly titled ‘Inventory of the Private Property of George IV’, GEO/ADD/19/8, was taken in 1820. Unlike other inventories which clearly grouped together items by their object types, such as furniture or clocks, this inventory utilises a different approach. All the items marked with the letter “P” in red ink, we are informed, denote George’s private property. All those without, it follows, are not the private property of George IV. But what does this category mean, and why is it being invoked here?

Since the reign of Queen Anne, successive laws and measures attempted to more clearly delineate what constituted crown property — that is, property that was inalienable and held in trust for the hereditary line — and what constituted personal or private property — that is, property owned by the monarch as a private individual that could be disposed of as he or she wished. Parliament wanted to rein in the monarch’s ability to alienate property, to prevent crown estates (and the income generated through their rents) being lost through sale, grants, gifts and pensions, and to combat corruption in royal expenditure. The distinction between crown property and private property was first properly articulated in the Crown Private Estates Act of 1800: this act established that monarchs could own some property as private individuals, which would be subject to taxes and duties, and which could be bequeathed in their wills, rather than just defaulting to crown property.[1] Private property here was allowed to be any property acquired through personal purchase, i.e., with funds from the Privy Purse, or that which had been given or devised to them by a non-royal subject.

However, distinctions between private and crown property were still far from clear-cut, and were subjected to heightened debate on the occasion of royal deaths. The deaths of Queen Charlotte in 1818 and King George III in 1820 resulted in controversies over the disposition of their property, particularly owing to George III’s failure to properly sign various re-draftings of his will, leaving only a wildly inapplicable will from 1770 as legitimate at the time of his death. In these and other cases, George IV, as Regent and King, interpreted — or perhaps more accurately, disregarded — the law surrounding property and inheritance to his own advantage. George IV steamrollered over the distinctions between private property and crown property in order to claim property as his rightful inheritance. Upon Queen Charlotte’s death in 1818, some of the jewels in her possession were considered to be hereditary property, but a portion of the jewels had been given as a personal gift to George and Charlotte by Muhammad Ali Wallajah, the nawab of Arcot, in 1767. In her will she directed these to be sold and the money divided up amongst her daughters. Instead, George IV claimed them as his personal property.[2] Upon the death of his father George III in 1820, George IV, in the memoirist Charles Greville’s words, likewise ‘[…] conceives that the whole of the late King’s property devolves upon him personally, and not upon the Crown, and he has consequently appropriated to himself the whole of the money and jewels’.[3]

In declaring money and possessions as his own private property, George was asserting his right to do with them as he pleased, and even dispose of and profit from them. Greville claims that George IV had hoped to sell off the large library collection amassed by his father, but was pushed by his ministers to instead donate the collection to the British Museum — rumours which cast his donation in a rather less benevolent light.[4] George’s actions were controversial, dividing members of Parliament and his family.

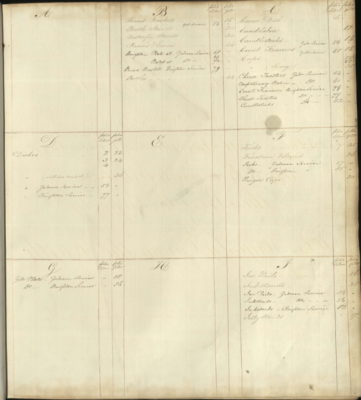

Figure 2. Inventory of the Private Property of George IV. GEO/ADD/19/8, p. ii. For a high-definition reproduction of this page, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here. Image: Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

It is in this context of growing concern around the distinctions between private and crown property that we should understand the ‘Inventory of the Private Property of George IV’. Upon examining the document, we find it lists plates, dishes, and other items belonging to George’s dining services at royal residences, primarily Carlton House, Brighton Pavilion and St. James’s Palace. An alphabetised index at the front of the volume breaks down the different types of objects listed in the inventory [Fig. 2]. The index reveals the remarkable range of items used to set the table for royal dinners, from the very grand to the seemingly humble — including bread baskets, knives, snuffer trays, cheese toasters, fountains and jelly stands. Notes alongside identify which ‘service’ the objects belonged to (i.e., which dining set) and the folio on which the items, divided into those gilded in silver and gold, are more fully described.

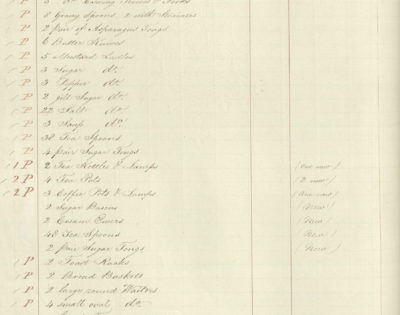

In the inventory itself, these dining items are described in greater detail, their quantities recorded, and their weights given [Fig. 3]. At the suggestion of the Inventory Clerk, Benjamin Jutsham, the letter ‘P’ was written in red ink to identify those items that should be considered the private property of George IV. The ‘Remarks’ column is used to note down whether items are newly purchased, have been re-gilded, removed to another property, or sold. There is a column for dates that goes unused. This indicates that the inventory was used as a working document that was continuously added to — a few items are listed as being purchased at the sale of the property of the Duke of York after his death in 1827. It can be difficult to disentangle contemporary notes from more recent annotations, but it appears a later hand has marked off the items against Jutsham’s receipt books, adding the initials ‘B. J.’ in pencil next to any items that can be cross-referenced in this manner.

The inventory enables us to identify what property was considered private property or not, as well as providing contextual clues about the reasons behind their classification. Most of the items recorded in Carlton House are marked as being private property. For example, the grandiose ‘4 large richly chased Tureens with handles representing the Ephesian Diana with her attributes’ supported ‘by Sphinxes, Serpent Handles on Covers’ listed at the top of this inventory, is recorded as private property. The tureens survive in the Royal Collection [Fig. 4] and we know that they were purchased by George IV when Prince Regent, in 1811.[5]

Fig 3. GEO/ADD/19/8 p. 68 detail. Image RCT © Her Majesty the Queen 2021. For a high-definition reproduction of this page, click on the image.

As we can see in Fig. 3, the items that are not classified as private property are typically noted as being ‘new’ purchases, or are clearly objects that George inherited. The inventory’s date is crucial to understanding why older purchases are regarded as private property, while newer purchases are not. The inventory is estimated to have been taken in 1820, the year in which George III died, and George IV ascended to the throne. At the time of his ascension, there were parliamentary concerns raised around whether property that been purchased by a sovereign, before he had succeeded to the throne, should be properly be considered crown property and therefore inalienable.[6]

This inventory does not record purchases after 1820, when George IV was reigning monarch, as private property. However, it makes clear that items purchased before George IV’s ascension to the throne, while he was still Prince of Wales, and Prince Regent, are to be considered his own private property – such as the set of 4 tureens purchased in 1811. Hence most of the items listed in Carlton House, which was fitted up at great expense during George’s years as Prince of Wales, were marked here and in other inventories as private property. It is plausible, then, to read this inventory not just as a record of what was classified as the “private property of George IV”, but as a political assertion of what should be classified as such.

Figure 4. One of set of four Tureens by Paul Storr, c.1802-4; silver gilt, 45.0 x 46.5 x 46.5 cm: RCIN 51695. Image RCT: © Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

Inventories did not simply act as records of the objects in royal households, but could be crucial evidence of whether property was considered as belonging to the crown or to the monarch as a private individual. George IV did much to blur the lines regarding what constituted ‘private property’ as opposed to ‘crown property’ during his time as Regent and King. But these inventories also display a heightened awareness of where his own property fell within these categories, and increased desire to create a paper trail documenting this. For, how different are the numerous inventories of George IV carefully marking out his private property, from the situation that George III’s trustees faced immediately after his death in 1820, in attempting to disentangle private from crown property:

‘There does not appear to have ever existed a full or correct catalogue of the Pictures being the King’s Private Property […] there has always been so much difficulty in distinguishing many of those which many of those which have been mixed with the Crown Collection, that the attempt tho’ occasionally made, has been as often abandoned.’[7]

_________

[1] John Kirkhope, ‘ “A Mysterious, Arcane and Unique Corner of our Constitution”: The Laws Relating to the Duchy of Cornwall’, Plymouth Law Review, i (2010), p. 139; John Kirkhope, ‘”The Duchy of Cornwall – A Feudal Remnant?” An Examination of the origin, evolution and present status of the Duchy of Cornwall’ (University of Plymouth, Phd thesis 2013), pp. 79-80.

[2] Matthew Winterbottom, ‘The Dispersal of Queen Charlotte’s Property’, in Jane Roberts (ed.), George III and Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste (Royal Collection Trust, London, 2004), p. 385.

[3] Charles C. F. Greville, The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV and King William IV, i (London, 1874), pp. 64-5.

[4] For more on this, see Robert Lacey, ‘The Library Of George III: Collecting For Crown Or Nation?’, The Court Historian, x, no. 2 (2005), pp. 137-47.

[5] https://www.rct.uk/collection/51695/set-of-four-tureens

[6] Thomas Erskine May, The Constitutional History of England Since the Accession of George the Third, 1760-1860, i (London, 1861), p. 208.

[7] GEO/MAIN/32621-32624, General memorandum of George III’s personal property, January 1820.