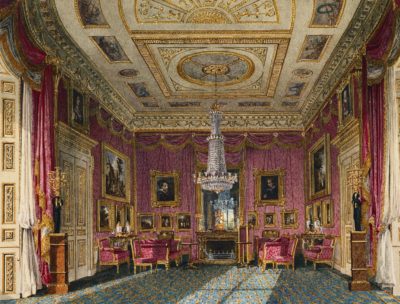

Fig. 1.Charles Wild (1781-1835), The Rose Satin Drawing Room, Carlton House (looking North) c. 1817, pencil, watercolour, bodycolour and gum arabic, from Henry Pyne, History of the Royal Residences. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 922180. (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

In an anecdote recounted in Fraser’s Magazine in 1841, the Inspector of Household deliveries at Carlton House, Benjamin Jutsham, explained to some bemused visitors why everything in the house was so meticulously arranged. Chairs, table-cloths, quires of paper — all were set out with mathematical precision. The inspector described that for George IV, order was “an indispensable quality, as well as in little as in greater things; and where there is no order … all soon becomes confusion”.

It was so important that he suggested ‘A place for every thing, and every thing in its place’ might well have been the motto of Carlton House.[1]

This drive for order is never clearer than in the numerous inventories of Carlton House, George IV’s first architectural passion. He was given the property when he turned 21 in 1783, along with a sum of money to do the place up. It was outmoded, and a little oddly-shaped: the house had previously belonged to his grandmother, Princess Augusta, and had stood empty since her death in 1772. It was built on a slope, meaning that the garden side of the house was on a different level to the street side.

George quickly set to transforming Carlton House into a palace worthy of a prince, embarking on major successive architectural and redecoration schemes, and racking up notoriously large debts in the process. He employed Henry Holland to transform the house in a French neo-classical style in c.1784-96, but then ‘ordered the whole to be done again under the direction of Walsh Porter who has destroyed all that Holland has done & is substituting a finishing in a most expensive and motley taste’.[2] Walsh Porter’s opulent redecorations carried out in c.1805-9 are preserved in the images of the interiors of Carlton House in William Pyne’s Royal Residences [Fig. 1]. John Nash in 1813-28, meanwhile, fitted out rooms in a gothic style and installed temporary structures in the garden to expand the space. Carlton House, therefore, was a continuous work in progress, the rooms conceived of as ‘stage sets, to be altered at will.’[3]

George IV is remembered for his patronage of the arts, collecting on a vast scale not seen since the days of Charles I, and fitting out his residences in decadent splendour. Yet he also keenly tracked the movements of his gargantuan collection, leaving behind a wealth of documentary information including numerous inventories of his royal residences. This prodigious record-keeping was partly due to his shifting architectural ambitions, which required the complete uprooting of objects and art to satisfy new plans. While George IV is notorious for his profligate spending, he also made great use of objects already in his possession when remodelling. Even seemingly fixed furnishings, such as chimneys, were moved around to suit new design schemes.[4] Items were therefore moved both within houses, and between properties. Such ambitions could only be made possible through a thorough stock-taking of his collections. It is through the various inventories that we can build up a picture of the scope and contents of his collections, and their movements.

What kinds of inventories of Carlton House can be found in the Georgian Papers?

The Coutts Inventory of 1793 (GEO/ADD/19/58: ‘Carlton House Inventory as Surety for a Loan of £60,000’)

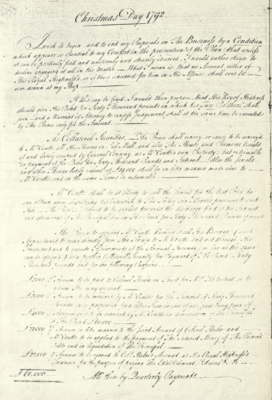

Figure 2. GEO/ADD/19/58: ‘Carlton House Inventory as Surety for a Loan of £60,000’ (1793). Click on the image to see a high-resolution scan of the whole document. Click here for the catalogue entry. Royal Archives/ (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2019.

This is the earliest inventory of Carlton House in the collections, and is also known as the ‘Coutts Inventory’ because it was drawn up by Thomas Coutts, a prominent banker, as part of a loan agreed with George IV as Prince of Wales on Christmas Day, 1792. Coutts & Co. is now one of the oldest banks in the world, and continues to serve an elite clientele, still being favoured by the Queen today.

This inventory forms part of a contract drawn up between George IV as Prince of Wales, General Hulse, his treasurer, and Coutts. Coutts only agreed to the loan if strong stipulations were put in place to ensure he was not left out of pocket. These included making Carlton House as collateral for the loan, as well as jewels and other items in the prince’s collection valued at £19,000 — hence the need to conduct an inventory.

The inventory also includes one of the earliest known plans of the property [Fig. 3], allowing us to see the layout of Carlton House prior to its nineteenth-century architectural transformations.[5]

Figure 3. Plan of Carlton House, 1793, p. 42 of GEO/ADD/19/58. Click on Image for a high-resolution scan of the whole document,

The Jutsham Receipts and Deliveries (GEO/ADD/19/21-23: ‘An Account of furniture &c received and deliver’d by Benjamin Jutsham on account of His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales at Carlton House.’)

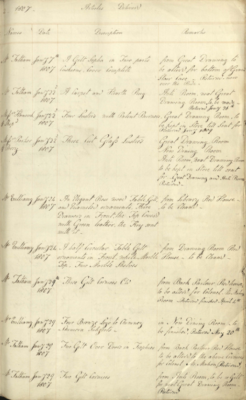

Figure 4. GEO/ADD/19/21. ‘An Account of furniture &c received and deliver’d by Benjamin Jutsham on account of His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales at Carlton House (1806-1820)’, p. 2. For a high resolution scan of the first half of this volume click on the image; for the catalogue entry, click here.

Although they are catalogued as part of the collection of inventories, the Jutsham Receipts and Deliveries books are more akin to day-books, recording Articles Received at Carlton House, and Articles Delivered from the house, and later to and from Windsor Castle. Rather than representing the collections at one given moment, then, the Jutsham books are a continuous record kept by the Inspector of Household deliveries, Benjamin Jutsham, of objects moving in and out of the collections. For example, we find that a cabinet inlaid with coloured stones and birds was received from the furniture maker Mr Morel on February 7th 1807, but was delivered from Carlton House to Mr Tatham to be remounted on March 9th 1807. A later note informs us that it was returned to Carlton on February 22nd 1810. There are three volumes: that with Jutsham I embossed on the spine encompasses items both received and delivered between 1806 and 1820 [Fig. 4], while Jutsham II accounts only for items received between 1816 and 1829, and Jutsham III only for items delivered between 1820 and 1830.

These books are invaluable accounts of when items were acquired by George IV and from whom they were purchased, showcasing the wide array of manufacturers, artisans and artists from whom George IV sourced his collections. They provide often quite detailed descriptions which can be used to match them to surviving objects. The volumes were treated as working documents in the Royal Collection, with updates added after the reign of George IV regarding the movements of objects. We can find annotations dating from as late as 1915, in the characteristic red ink used by Queen Mary (1867-1953) who used the Georgian accounts and inventories to reassemble dispersed royal collections.

Catalogues of Arms (GEO/ADD/19/41-45, ‘A Catalogue of arms: the property of His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales at Carlton House.’)

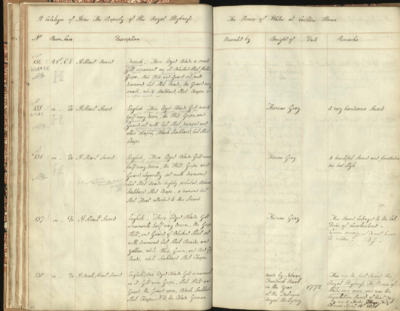

Figure 5. GEO/ADD/19/41. A Catalogue of Arms, Vol. 1 (1781-1805). For a high resolution scan of the first half of this document, click on the image. For the catalogue entry, click here.

After George IV was denied the opportunity to enter active military service by his father, King George III, he directed his passions instead to amassing a large collection of martial dress and weapons, which he housed in Carlton House. Ackerman’s Microcosm of London in 1808 described his military ‘museum’: ‘It occupies five rooms on the attic story ; the swords, firearms, &c. are disposed in various figures upon scarlet cloth, and inclosed in glass cases: the whole is kept in a state of the most perfect brightness. Here are swords of every country, many of which are curious and valuable, from having belonged to eminent men.’[6]

These items are recorded in the Catalogues of Arms, also compiled by Benjamin Jutsham, in five volumes that list 3,291 items. As Kate Heard has described, Jutsham’s entries are not just bare-bone descriptions, but can also include commentary on the history of the items listed, which ‘elevate[s] these objects from items of everyday use to memorials of an illustrious career’ – such as noting that no. 138, ‘A Small Strait Sword’, was ‘the first Sword His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales ever Wore.’ [See Fig. 5]. [7]

The Carlton House Inventories

The Carlton House Inventories appear to have numbered 26 volumes originally identified by letter codes of which 15 survive in the Georgian Inventories. This broad category includes the Coutts inventory described above. Inventories were typically grouped by type of object, such as ‘Furniture, ‘Super Furniture’, ‘ Plate glass, stoves, &c.’, and the contents of ‘Riding House Stores’. A flurry of these inventories were drawn up from 1826, the year in which George IV decided to abandon Carlton House as his London residence. At this stage, it was deemed architecturally unsound, and the following year it would be demolished. The inventories were therefore useful to assess what items needed to be sent to furnish other properties, including Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, and St James’s Palace.

This is only a snapshot of some of the documents that fall under the capacious category of ‘inventories’ in the Georgian Papers. The inventories have been heavily utilised in scholarship to inform our understanding of the shifting layout, design, and placement of artwork in Carlton House, the lost Georgian palace. They have been vital to reconstructing the original arrangement of Carlton House with ‘every thing in its place’. Yet there is still much the inventories have to offer us. The rest of this exhibition will illuminate some of the ways the inventories can be read in a different light, as political or social records. The next section will focus on one inventory in particular: an inventory of the private property of George IV, taken in approximately 1820.

______

[1] [William Henry Pyne] ‘The Greater and Lesser Stars of Old Pall Mall’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, xxiii (Jan.-June 1841), p. 690.

[2] Joseph Farington, The Farington Diary, ed. James Greig, 8 vols (London, 1922-8), iii. 214: entry for 3 May 1806.

[3] Carlton House, The Past Glories of George IV’s Palace (London, 1991), p. 36.

[4] Carlton House (1991), p. 15.

[5] Prior to this, we have floor plans of Carlton House created by Henry Holland in 1784, also in the RCT collections: https://www.rct.uk/collection/918937/carlton-house-in-march-1784.

[6] Rudolph Ackermann and William Henry Pyne, The Microcosm of London: Or, London in Miniature, iii. (London, 1904), 109; For the initial reference, see: Carlton House (1991), p. 47.

[7] Kate Heard, ‘A Naive and Sentimental Soldier? George IV and the Art of War’, in Kate Heard and Kathryn Jones (eds.), George IV: Art & Spectacle (Royal Collection Trust, 2019), p. 136.