The 18th Century Materializes on Stage

By Karin Wulf and Arthur Burns

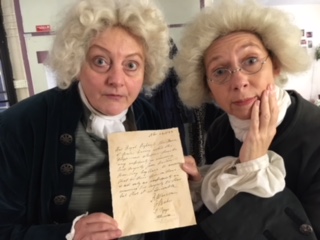

Stephanie Jacob as Sir George Baker and Amanda Hadingue as Sir Lucas Pepys in the Nottingham Playhouse production of The Madness of George III with a doctors’ bulletin prop produced with the help of the Georgian Papers Programme. Photo: courtesy of Jane Eliot-Webb, stage manager, Nottingham Playhouse (as are all images below unless specified otherwise).

There is so much eighteenth century on view in the much acclaimed Nottingham Playhouse staging of Alan Bennett’s The Madness of George III. The Georgian Papers Programme had a wonderful opportunity to host lead actor Mark Gatiss at Windsor Castle to view some of the archival materials selected to reflect the play’s themes. Those are now in the online exhibit hosted here on the GPP site. The texts in the exhibit include letters from the Prime Minister, William Pitt, and the king’s specialist doctor, Francis Willis as well as King George III’s own reflection on his illness.

Mark Gatiss views documents from the Georgian Papers archive in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle as he prepares for his role as George III. Photo: Royal Collection Trust © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Under Adam Penford’s direction, the play, the lines, the plot, and the evergreen themes of how to judge the well-being of a head of state are all extraordinarily vivid, but the significance of eighteenth-century material and visual culture is especially acute. There were intimate connections between late eighteenth-century drama and politics. Political players and their followers dramatized their own stances through pointed attendances at and reactions to specific productions. There were riots over access to the theatre which drew on discourses of English liberty; and there was cross-over between the casts of theatrical life and politics — remember that the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan appears as a key player in Bennett’s play. For a political drama such as Bennett’s, such considerations inevitably encourage attention to achieving a convincingly ‘Georgian’ feel in a production. In Bennett’s play, moreover, the key significance of the physical settings (Windsor, Kew Palace, St Paul’s) and the pivotal role played by letters, reports and official papers in driving the action, makes the representation of these things all the more important. Now that audiences worldwide are getting at look at the play through the filming broadcast by National Theatre Live, it’s worth underscoring just how much this visual and material culture contributes to the play. And, just as other aspects of the drama have offered an opportunity to consider the history revealed through the Georgian Papers Programme, the staging prompt us to reflect on the relationships between text, object and image.

Nottingham Playhouse has a distinctive — once traditional but now increasingly rare — approach to sets and costumes, building in-house rather than bringing in or renting from outside. On site the set designers have produced creations that are based on eighteenth-century items. As Claire Thompson, the head of the paint shop, describes in a short film on the theatre’s Facebook page, the back cloth depicting London’s Saint Paul’s Cathedral is based on a painting by Canaletto dating from the 1750s. The front cloth depicting theatre drapes is also based on cloths used in eighteenth-century theatrical productions. It is a perfect situation for creatively using the eighteenth-century texts central to the story.

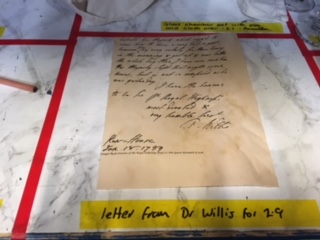

The archival materials of the Georgian Papers Programme play a critical role onstage. Just as the sets and costumes have been exquisitely crafted to reflect an eighteenth-century sensibility, the volumes of paper that appear in the actors’ hands, the reams of papers that the king reads, and writes, and strews about, that the doctors and ministers write, read from, and send around, and that we know the equerry and other courtiers were writing to log their experiences, are facsimiles of materials preserved in the Royal Archives’ Georgian Papers. Working with the production staff, the Georgian Papers team selected specific, relevant texts for use in the production, and provided images to Nottingham Playhouse. There, the team worked up the pages, treated to look not like they came from a twenty-first century printer, but like linen and rag paper, laid on a desk and written on with quill and ink in eighteenth-century hand.

The St Paul’s backcloth painted by the Nottingham Playhouse’s paintshop: Photo: (c) Manuel Harlan for Nottingham Playhouse

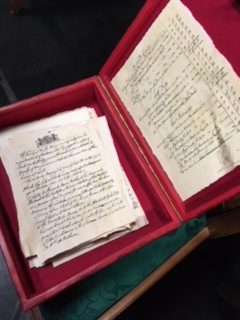

We can share some images here of the texts as props, waiting to go onstage and held by an actor, or settled into one of the king’s famous red despatch boxes. What difference does it make to include facsimiles of King George III’s own writing, or of documents once held by his doctors and others?

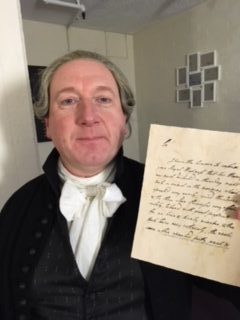

Adrian Scarborough as Francis Willis holds up a facsimile of the first page of Willis’s medical report of 18 Jan 1789 (from the Georgian Papers RA MED/ 16/1/44)

The second page of a facsimile of a bulletin by Dr Willis on the King’s health to the Prince of Wales dated 18 Jan. 1789 (from the Georgian Papers, RA MED/16/1/44) sitting on the prop table backstage at Nottingham Playhouse

Certainly, the king’s or the prime minister’s handwriting suggests something of the author’s personality, as well as the subjects of their concern and interest. For those who work with archival materials it is a common experience that encounter with the manuscript original of a letter already well-known from accurate (and possibly more readily intelligible) printed reproductions can provoke a fresh feeling of intimacy with the long-dead, even as one appreciates that this is in many senses illusory. During the visit to the Royal Library to view the items in the exhibit prepared for the play, Gatiss and Arthur Burns confronted a letter in the archive in which Queen Charlotte writes with palpable urgency to her absent husband of her loving anticipation of his return home; they both felt they ‘knew’ her better than before through reading her prose in her own hand, despite already being familiar with the couple’s famed domesticity. Working closely with the documents helps us to appreciate how they can also speak directly to state of mind, with agitation or distress palpably present in rapid blotched scrawls with frequent deletions and amendments, or in an especially heavily inked phrase, while high-status documents containing key instructions are evidently penned and likely recopied with painstaking care. For a British audience, for whom the concept of a ‘doctor’s note’ is a common cultural reference point for illegibility, to see the doctors’ daily bulletins on George III to the Prince of Wales and others, written clearly — and signed sometimes by all of the attending doctors, and sometimes by only one in what constituted, in effect, a ‘minority report’ —, tells us something significant about the processes through which these texts were produced.

Dr Willis (Adrian Scarborough) discusses a medical report with William Pitt (Nicholas Bishop) in The Madness of George III at Nottingham Playhouse. Photo: (c) Manuel Harlan for Nottingham Playhouse

Facsimile documents in a red despatch box used in the Nottingham Playhouse production of The Madness of George III

The onstage documents most importantly, as props must, are meant to do a job. They must look the part, which likely means that they must feel, look and function for the actors as letters, memoranda and other eighteenth-century texts that are invoked in the moment. One key consideration here is size — as important to the props team as to the GPP working with them was to reproduce the almost literal ‘weight’ of the documents. For the actors, we suspect, one response the documents might produce, is an awareness of the ephemerality of much key documentation of eighteenth-century governance in comparison with official documentation of our own times, with the relative authority of print and handwriting in some senses reversed, and the significance of the personal in the authentication of communications and authorizations clearly apparent.

The use on stage of facsimile images of manuscripts from the Royal Archives also reminds us of the layers of representation that we contend with in any digital archiving project. The original items are in the Round Tower at Windsor. Scans of those items, when catalogued, are now online, available to the public and to researchers for study and for projects such as our online exhibits. The scans can be used to facilitate transcriptions, from which digital analyses are producing new understanding of the materials and the period. The digitized text is itself in several different forms. The first point is one that scholars of material and print culture, technology and the digital humanities know well—these various forms are distinct. We can research different aspects through each — the text, the digitized text, the material object, the image of the text on the page. But one must never lose sight of what is lost as well as gained in each transformation. Those teaching with digital texts, for example, are familiar with the need constantly to remind students of what is not as apparent as might be the case in the archive — how big is the document? How does it lie next to other material? Are there blanks or missing sections? What is on the back of the sheet? (The GPP, it should be noted, like most digital archiving projects, is digitizing blank pages as well as those with writing on them.)

And how do these different forms of text and object interrelate? A feature of creating the digital archive through the Georgian Papers Programme is the facility to work across these media. New work from archivists and researchers in the Programme is illustrating just how potent the combination can be, revealing new insights about what was written, and why, and how, as well as the wide and deeper contexts for the production of the full corpus of materials. And in the meantime, we can enjoy the artful display and utility of text and object in this marvellous dramatic production.

Mark Gatiss as George III discusses official papers with his ministers in the Nottingham Playhouse production of The Madness of George III. Photo: (c) Manuel Harlan for Nottingham Playhouse

There are still opportunities to see screenings of the Nottingham Playhouse production of the Madness of George III across the world as part of the Encore! programme of National Theatre Live: for more details, visit the NTLive website.

The virtual exhibition of documents specially prepared for this production can be viewed on this website here.

We are very grateful to Jane Eliot-Webb, Company and Stage Manager at Nottingham Playhouse, for her help in preparing this blog, and to all the cast, production team and crew at Nottingham Playhouse for their enthusiastic engagement with the Georgian Papers Programme.

[…] The 18th Century Materializes on Stage: a blog reflecting on how the 18th century was realised in the Nottingham production. […]