While the inventories can tell us a lot about the objects in the royal residences, they also provide a window into the structure of the royal household itself and its role in royal patronage. The staff members who deputised in the acquisition of art, who managed the collections, and who directed the compilation of catalogues and inventories, are not nameless figures consigned to the shadows of history, but are frequently recorded and known to us. Therefore the inventories can also be viewed as records of individuals in the household and their daily working lives. In this section of the exhibition, we’ll dive deeper into the question: who was it was that actually took the household inventories?

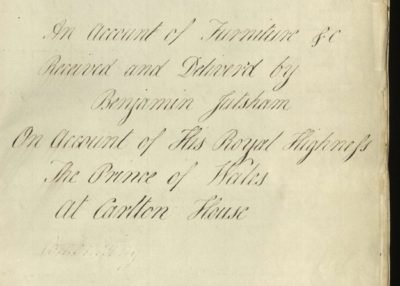

Figure 1. An Account of Furniture &c Received and Deliver’d by Benjamin Jutsham on account of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales at Carlton House: vol. 1, receipts and deliveries 1806-1820., GEO/ADD/19/21. Click on the image to access a high-resolution scan of the first half of this volume. Click here for the catalogue entry. Image @Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

The name stamped across many of the inventories, ledgers, and day books in the Georgian Papers is that of Benjamin Jutsham (c.1766-1836), employed by George IV at Carlton House from 1803. Jutsham held a number of roles in the royal household, primarily as Inspector of Household Deliveries, but also as the Inventory Clerk and Keeper of the Royal Armoury, effectively overseeing the day-to-day process of objects coming in and out of the household collections. He worked in the royal household until his death in 1836, over a period of over 30 years that saw George’s transition from Prince of Wales, to Prince Regent, to King, and his brother William IV’s ascension to the throne. A seemingly tireless worker, his name is frequently referenced in scholarly work, but his career is rarely explored.

Benjamin Jutsham’s personal history prior to his position at Carlton House is somewhat opaque.[1] It is likely that Jutsham came from a family of some social standing. He was born in London in 1766, and in February 1803, just before he began working at Carlton House, he married Arabella D’Atournou, a French Huguenot whose family had sought refuge in England in the mid-eighteenth century. Her father, a merchant, had returned to France in the 1770s after going bankrupt, leaving her in the care of her uncle François, a jeweller.[2] From at least the 1820s, Benjamin and Arabella lived in St Michael’s Grove, Brompton, a fashionable ward of London populated by many artists and actors, located in present-day Kensington. They don’t appear to have had any children together, and Jutsham turned his attention instead to his nephew Francis Read, a builder and bricklayer. He used his position in the royal household to help secure a position for his nephew as a master bricklayer during Nash’s redevelopment of Buckingham House in 1825-9 (despite being somewhat underqualified), and left him money in his will.[3]

At the time of Jutsham’s initial employment, Prince George’s racking up of large debts was not for the first time a source of national embarrassment. A large portion of these debts had been incurred through the Prince’s extensive and elaborate building and decoration schemes at his London residence, Carlton House, and at his Pavilion in Brighton. As his former treasurer Colonel George Hotham (1741-1806), had once admonished George, he was ‘totally in the hands, and at the mercy of your builder, your upholsterer, your jeweller and your tailor’.[5] Parliament finally agreed in February 1803 to grant the Prince of Wales an additional income of £60,000 per annum for three years to cover some of the debts, but refused to help with debts accrued after his marriage settlement of 1795. Instead the Prince was required to reserve £50,000 a year to pay off the remainder, and promise to rein in his extravagant lifestyle.[6] It is possible that the timing of Jutsham’s employment in 1803 was more than just fortuitous, representing a concerted effort more carefully to control the Prince’s expenditure within the household.[7] The position “Inspector of Household Deliveries” was a newly created one within the Lord Chamberlain’s department, that Jutsham appears to have been the first to occupy. For the majority of his working life Jutsham was based at Carlton House, but we later find him working as Inspector of Household Deliveries at St James’s Palace after George IV’s death in 1830.

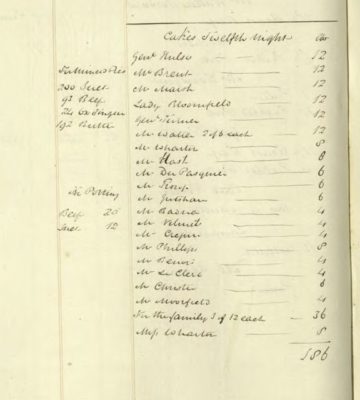

Figure 2. List of recipients of the Twelfth Night Cake, 1819: GEO_MENUS/MRH/MRHF/MENUS/MAIN/MIXED/5. To view in high definition click on the image. To read the catalogue entry, click here. Image @Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

It was a respectable and well-remunerated position. When he was first hired in mid-1803, Jutsham was on an annual salary of approximately £142 and 10 shillings (See: GEO/MAIN/88853-88982: ‘Quarterly account book for George, Prince of Wales dating 1800-1809‘). But by the time he was appointed inspector at St James’s Palace, he was paid £500 plus £91 5s. board wages from the Lord Steward’s department, and given compensation in lieu of articles in kind of £29 5s., making his total annual salary a whopping £620.10s.[8] For context, this was a level of salary that could support a well-to-do family with a handful of servants of their own, placing him just within the echelons of polite society.[9] He was clearly considered as one of the senior staff members in the royal household: we can see in the menu books for Christmas day at Carlton House in 1819 (GEO_MENUS/MRH/MRHF/MENUS/MAIN/MIXED/5) that Jutsham was one of the lucky few to receive a portion of the Twelfth Night cake, along with other high-ranking members such as George’s Treasurer, Clerk Comptroller, and Housekeeper.[10] It was also a position which placed him in close communication with the King, and afforded their relationship a degree of informality.

Benjamin Jutsham’s methodical, assiduous character is clear to anyone who reads through the detailed records he kept as Inspector of Household Deliveries and Inventory Clerk. One gets the sense that we have much to thank Jutsham for in bringing order to George IV’s multitudinous collections of furniture, clocks, paintings, armoury, plates and more, and his inventories display a degree of care that goes beyond that present in earlier records. It was his diligent approach to the management of household collections, coupled with his easy familiarity with the King, that warranted his appearance in a number of anecdotes of the court of George IV in nineteenth-century periodicals and diaries. One particular incident at Carlton House between Jutsham and Colonel George Hanger (1751-1824), a rowdy and dissolute member of Prince George’s inner circle, brings to life the character of this ‘confidential and much esteemed officer of the household.’[11]

After George had become king, it is reported, George Hanger visited the library at Carlton House and was reprimanded by Benjamin Jutsham for spitting on the carpet. This quickly developed into a dispute about a missing book, with Hanger harrumphing at the accusation that he had failed to return a volume, and Jutsham demanding its return before any other books could be borrowed. Jutsham is painted here as punctilious and reliable, a man whose ‘bare assertion was equal to another man’s affidavit’. His calm yet wry demeanour plays the foil against Hanger’s explosive anger, the latter angrily exclaiming “Go to Bath, you demi-reptile! Not take my word! I shall remember you for this, Master Benny Jutsham!”[12]

Robert Dighton: Lord Coleraine (George Hanger). Watercolour . RCIN 990848. Image Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021

This anecdote and others like it also show how closely entwined staff like Jutsham were in social life of the court. They could be recognisable, familiar figures to those moving within royal circles, and I would argue, merit historical recognition. There is scope for much greater research into the household structure of the Georgian monarchy, particularly in uncovering the lives of royal servants. Lucy Worsley’s book Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (2010) and counterpart documentary series has looked at the staff of the early Hanoverian court, inspired by William Kent’s staircase paintings of royal servants at Kensington palace in the 1720s. Sadly no similar group portrait exists for the household staff of the later Georgian period, nor any equivalent in-depth study. The collection of the Georgian Papers can be an invaluable resource for recovering the lives of royal household staff, especially in conjunction with the wonderfully rich (and digitised) Database of Court Officers: 1660-1837 which can be used to identify individual household staff members and their role. And in the case of Benjamin Jutsham, we might yet put a face to a name. Though its whereabouts are currently unknown, a portrait of Jutsham by the painter James Scott was displayed at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1821, a painting that one day I hope we’ll be able to track down.

Furthermore, looking at the vital role played by individuals such as Benjamin Jutsham in the compilation of inventories and organisation of the household collections forces us to consider the extent to which royal patronage was dependent upon the machinery of administration. In the book that accompanies the recent exhibition George IV: Art & Spectacle at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, Kate Heard and Kathryn Jones describe the inventories as ‘compiled by his staff in an attempt to keep track of his gargantuan collection’.[10] In the context of studying the royal household, I think this raises interesting questions. Should these voluminous inventories be viewed as the work of George IV or of his household staff? Where does the agency lie in the creation of these records, and for whose benefit were they created? As we saw in Section 2, the inventories of George IV were taken at various points as his passions shifted from furnishing and fitting out Carlton House, to Brighton Pavilion, to Buckingham House, and then to Windsor Castle. But it was household officers such as Benjamin Jutsham that made George’s architectural and artistic ambitions realisable. While the inventories have often been cited as evidence of the artistic legacy left to us by George IV, I suggest they also illuminate the role of the household in underpinning royal patronage, collection and curation.

______

[1] Rory Muir, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune: How Younger Sons Made Their Way in Jane Austen’s England (London, 2019), pp. 22-3.

[2] For more on the D’Atournou family, see Daniel Bourchenin, ‘Béarnais à Londres: Les Datournou’, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire du protestantisme français, lxxxii, no. 3 (1933), pp. 347-52.

[3] J. Mordaunt Crook & M. H. Port, The History of the King’s Works, vi, 1782-1851 (London, 1973), p. 139; The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1870/194: Will of Benjamin Jutsham of Kensington, Middlesex, 30 Dec. 1836. Description available at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D284409.

[4] E. A. Smith, George IV (New Haven and London, 1999), p. 89; ibid., p. 32. The quotation is from a letter of Hotham to George, Prince of Wales, 27 Oct. 1784: GEO/MAIN/16476-7.

[5] Smith, George IV, pp. 91-2.

[6] See GEO/MAIN/30765 for a possible lead on this. ‘Circular letter from General Samuel Hulse to officers of the establishment of George, Prince of Wales regarding duty assessment of their salaries by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, Duchy of Cornwall Office, 30 December 1803’.

[7] Royal Household Index 1660-1901, accessible through findmypast.com; Chamber Administration: Lord Chamberlain, 1660-1837′, in Office-Holders in Modern Britain: Volume 11 (Revised), Court Officers, 1660-1837, ed. R O Bucholz (London, 2006), pp. 1-8. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol11/pp1-8 [accessed 28 January 2021].

[8] Rory Muir, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune (London, 2019), pp. 22-3.

[9] Venetia Murray, High Society: A Social History of the Regency Period, 1788-1830 (London, 1998), p. 190.

[10] [William Henry Pyne] ‘The Greater and Lesser Stars of Old Pall Mall’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, xxiii (Jan.-June 1841), p. 621.

[11] Ibid – I highly recommend reading this comic account, which can be accessed on Hathi Trust here.

[12] George IV: Art & Spectacle, ed. Kate Heard and Kathryn Jones (Royal Collection Trust, 2019), p. 15.

END OF EXHIBITION

Exhibition credits: text and selection of objects: Holly Day

Editorial support: Karin Wulf and Arthur Burns