Michael Jibson as King George in the London production of Hamilton, 2018. Picture: Matthew Murphy

Following the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, widely understood to be the culminating battle of the war, the king’s question in Hamilton is for the Americans, but also for the British. That battle was the result of complex and disappointing failures on the part of the British military, and especially perhaps an excursion in the Caribbean which delayed the naval response to French support for the Americans. This sealed the fate of the most important British army then in the field, which under its Commander, General George Cornwallis, surrendered to Washington in October 1781.

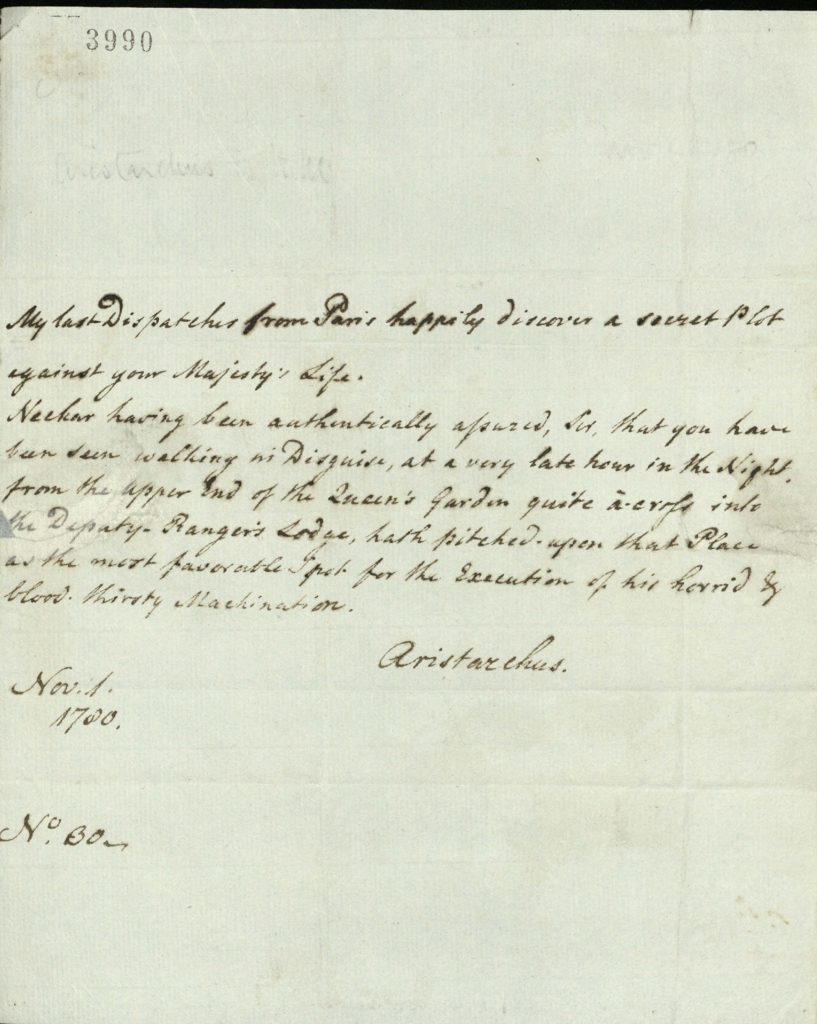

5. Aristarchus, the King’s spy

Letter from the spy Aristarchus to George III

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/3990

Amongst the official papers of George III are several from an intelligence source, codenamed ‘Aristarchus’ (presumably after the ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician). The identity of this person remains unclear, though it is thought that he was a middle-aged man in the early 1780s, from which period the bulk of the correspondence dates. He appears to have been active in London in this period, and to have supplied George III with information about continental politics and military matters.

Amongst the official papers of George III are several from an intelligence source, codenamed ‘Aristarchus’ (presumably after the ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician). The identity of this person remains unclear, though it is thought that he was a middle-aged man in the early 1780s, from which period the bulk of the correspondence dates. He appears to have been active in London in this period, and to have supplied George III with information about continental politics and military matters.

In this letter, dated 1 November 1780, he warns that it is known that King is going about incognito at night, and is therefore much less safe than he might have imagined, as the French authorities are aware of his movements.

Click on the document image to read it in full in high resolution.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

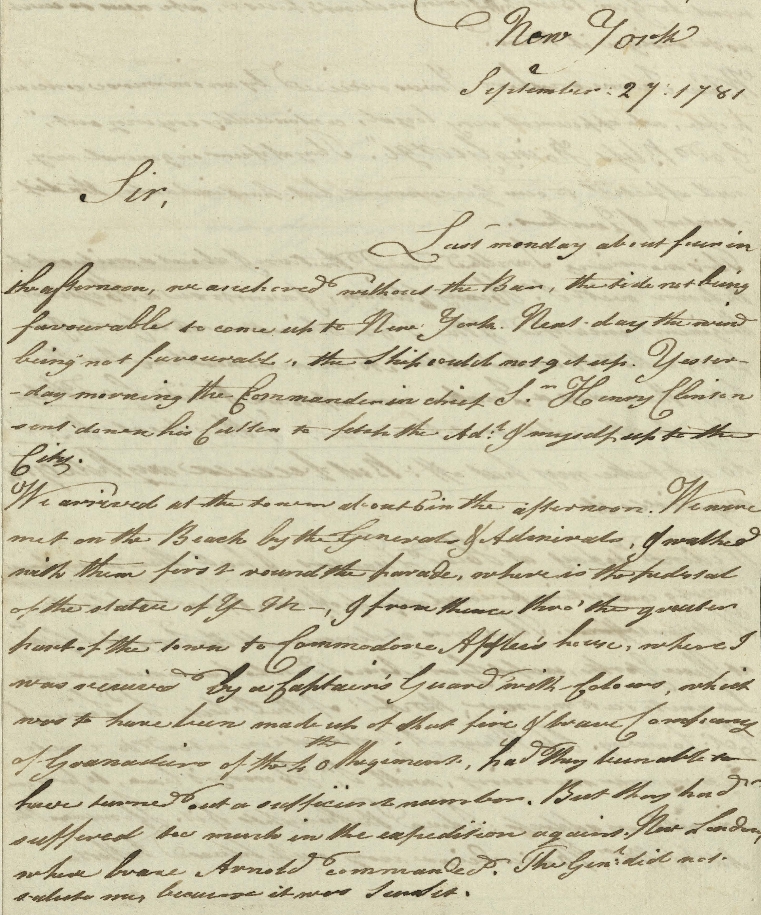

6. Prince William reports from New York City

Letter from Prince William to George III, written from the Commandant’s House in New York 27 September 1781

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/44630-1

This is a letter to George III from his son, Prince William, later King William IV. The young prince, at the very beginning of his career in the Royal Navy, describes his arrival in New York aboard HMS Prince George in September 1781.

Prince William describes walking by the pedestal of the statue of George III, which once stood on Bowling Green. The statue had been pulled down by the ‘Sons of Freedom’ in July 1776 following the first proclamation of the Declaration of Independence made in front of George Washington and his troops.

William’s meeting with General Benedict Arnold and the few soldiers from the 40th Regiment who had survived the raid of the Connecticut port of New London appears scant consolation. The raid was a success, but the Connecticut militia stubbornly resisted British attempts to capture Fort Griswold, and both sides suffered heavy casualties, these including the regiment’s commanding officer. William’s consternation is clear at seeing the grenadiers reduced to a small group, having suffered so much on the expedition – on the American side, rumours of summary executions of surrendering prisoners proved powerful propaganda for the Revolutionary cause.

In stark contrast with this, Prince William tells of how, at his arrival, he was received on shore ‘by an immense concourse of people, who appeared very loyal, continually crying out, “God bless King George.”’ noting that prominent among them were Quakers, one of whom apologised for his failure to doff his hat to the prince.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

For more on William and his naval career, read the blog by Professor Andrew Lambert on the Georgian Papers Programme Website.

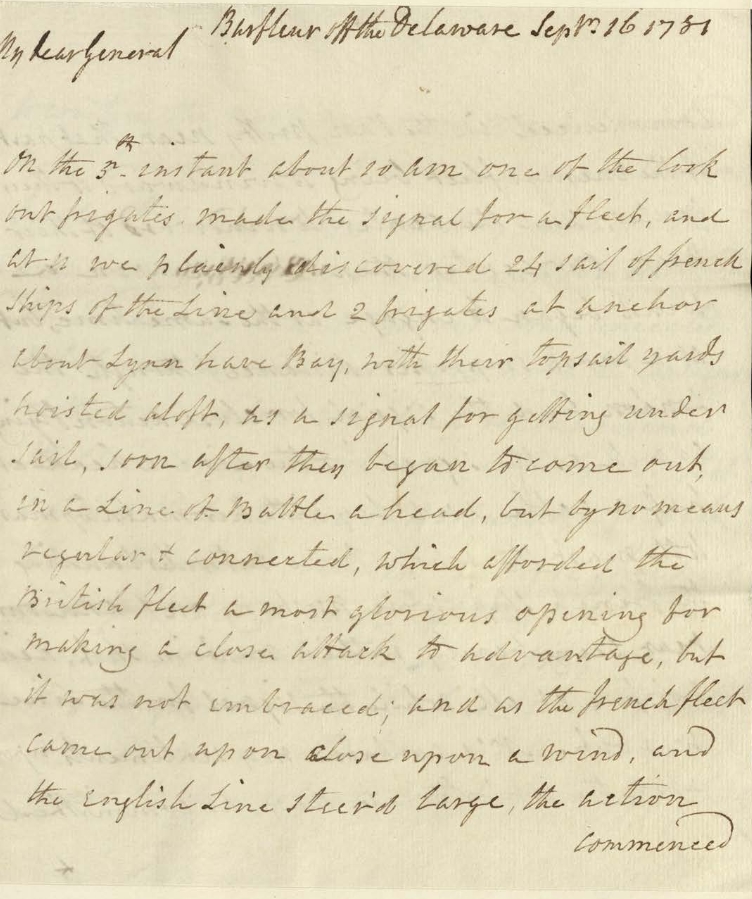

7. Intelligence networks: George III’s inside track on the Battle of Chesapeake Bay, 1781

Letter from Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood to General Jacob de Budé, 16 September 1781

Georgian Papers, de Bude Papers, GEO/ADD/15/0642

This is a hitherto unknown document recounting the events of the Battle of Chesapeake Bay, the crucial naval battle in September 1781 which led to the defeat of the British army at Yorktown and the independence of the United States of America.

It was written by Samuel Hood, a great hero of Horatio Nelson, and is found among the papers of General de Budé, aide-de-camp to George III. Rear-Admiral Hood explains to de Budé, and thus the King, what went wrong and his own role in the engagement and aftermath.

The letter – and the long-running correspondence of which it is part – shows how George III used his patronage to extend his own intelligence network independent of the official governmental channels. It is also important for the biography of Hood, one of Britain’s most notable naval officers, for it also helps explain how Hood survived the controversy with his career intact.

A notable feature of the Georgian papers archive is the survival of papers associated with second-order individuals such a de Budé, whose papers have hitherto largely escaped the attention of researchers. These promise to reveal much about the workings of the Court both in politics and as a social world.

For a more detailed discussion of the significance of this letter, see the blog by Dr James Ambuske on the Georgian Papers Programme Website.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.