Michael Jibson as King George in the London production of Hamilton, 2018. Picture: Matthew Murphy

The one repeating line in the songs that Hamilton’s King George III sings is ‘Oceans rise, empires fall.’ Though in Hamilton the audience is introduced to the king in the context of the American Revolution, the complexity of his reign, including his personal and family life, is more fully revealed through the archival materials and the research undertaken by the Georgian Papers Programme. The selections here show the king’s strong interests in science and Enlightenment political thought, the family life of King George, Queen Charlotte, and their 15 children, the emphasis on women’s literary and educational endeavours, and the global interests of the entire family.

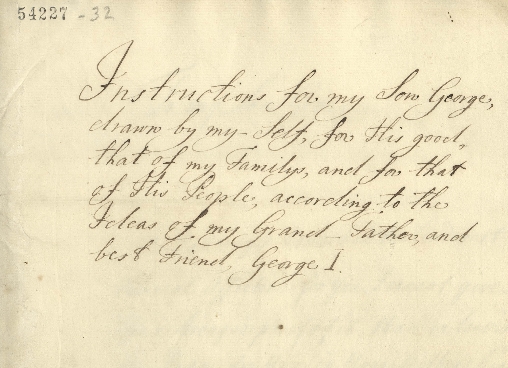

11. The royal apprentice: fatherly advice on kingship

Instructions from Frederick, Prince of Wales, to his son George, 18 January 1749

Georgian papers, GEO/MAIN/54227-54232

This touching and highly personal document was written to the future George III by his father, Frederick, Prince of Wales. This document is all the more poignant because the Prince himself would never be the king he advised his son to be. Here we see Frederick instructing his 10-year-old son in kingly conduct with regards to economy, war and Hanover, along with more fatherly advice:

‘I know that you will have allways the greatest respect for your good Mother… and all you can do, consistently with Your own Interest, for Your Brothers and Sisters, you certainly will do. You must not reckon Yourself only their Brother, but I hope you will be a kind Father to Them.’

Dated 1748/9, this document was written only a few years before Frederick’s sudden and unexpected death in 1751 aged only 44. We can only speculate how much this document meant to George and how different life may have been had the charismatic and confident Frederick lived to succeed his own father, George II. King George III’s mother, Augusta, Princess of Wales, indeed as her husband had counseled remained an important presence in George’s life until her death in 1772, and his relationship with his first Prime Minister, Lord Bute, both in and out of office, was complicated by rumours that the premier had conducted an affair with the Princess.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

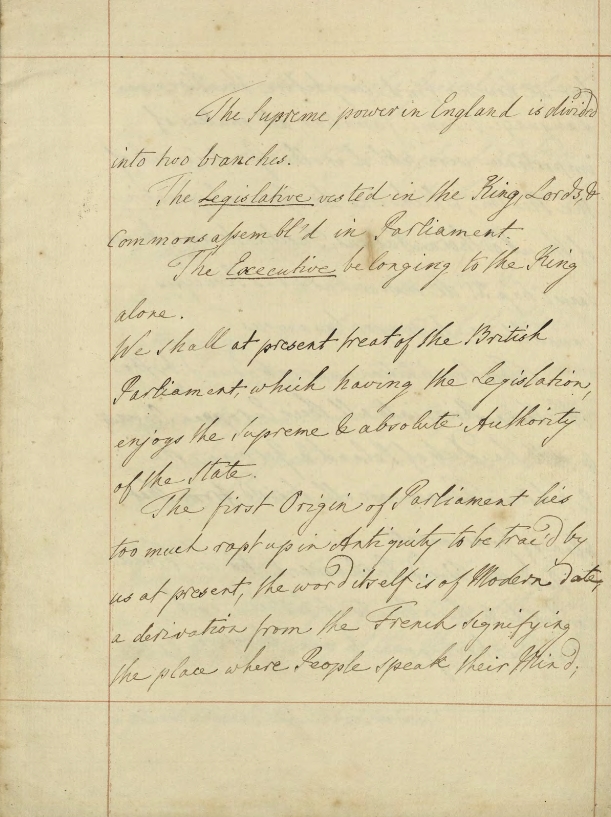

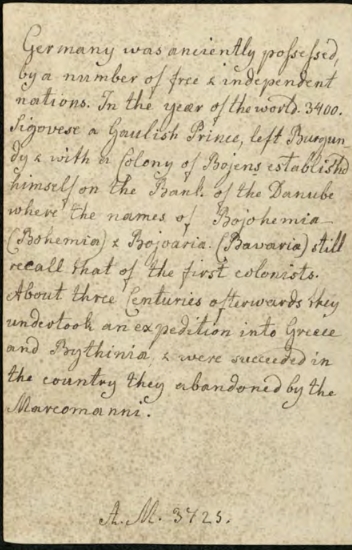

12. George III as a prince of the Enlightenment

Fair copy of essay on the legislative and the executive, undated

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/32/1022

Constitutional debates on the role of the aristocracy, Parliament and the King had characterised much of British politics since the Glorious Revolution. Far from being resolved by the time of the reign of George III, they were if anything rekindled by the ascension to the throne of a young energetic monarch who was keen to reassert royal authority and patronage. This unfinished essay in constitutional theory, which shows the king thinking deeply about these issues, was thus written in the context of extensive public discourse on the topic involving Burke, Wilkes and Fox, to pick out but some of the more prominent critics. It even draws from the French philosophe Montesquieu specifically both in the language of the ‘supreme power’, and also in articulating the separation of the executive and legislative branches of the state. It thus locates the King firmly in the context of the Enlightenment.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

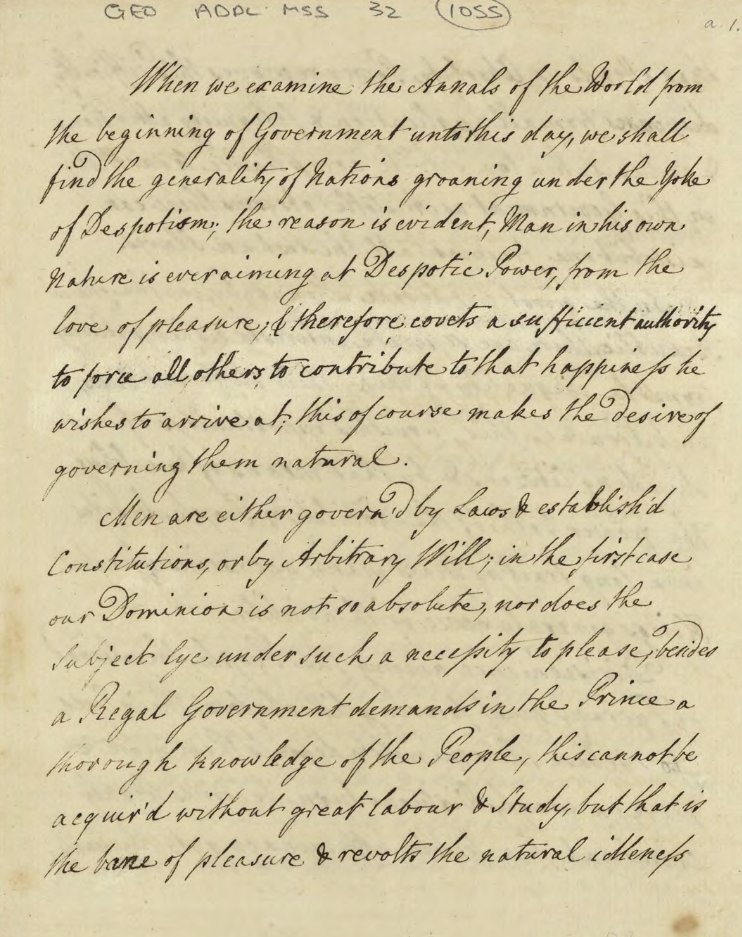

13. George III on despotism

Draft essay on despotism, undated

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/32/1055-7

Among the papers of George III is an essay ‘On Despotism’, in which he sets out clearly why it is undesirable to govern a people in a despotic manner. This might surely have amused, or perhaps bemused, many of George’s former American subjects.

This is one of the very large number of ‘essays’ – which range from a few scrappy notes to extended prose writings – found among George’s papers. Few are dated, and the Georgian Papers Programme team is currently thinking about how best to understand these fascinating documents. This one most probably dates from the late 1750s or early 1760s, and may reflect the period in which George was being tutored by Lord Bute, his first prime minister, consciously preparing himself for rule, and with the intention of ‘rebooting’ the Hanoverian monarchy.

In this understanding of the best way to rule, we can recognise that version of King George to whom many Americans at first appealed to rescue them from despotic rule – by the British parliament.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

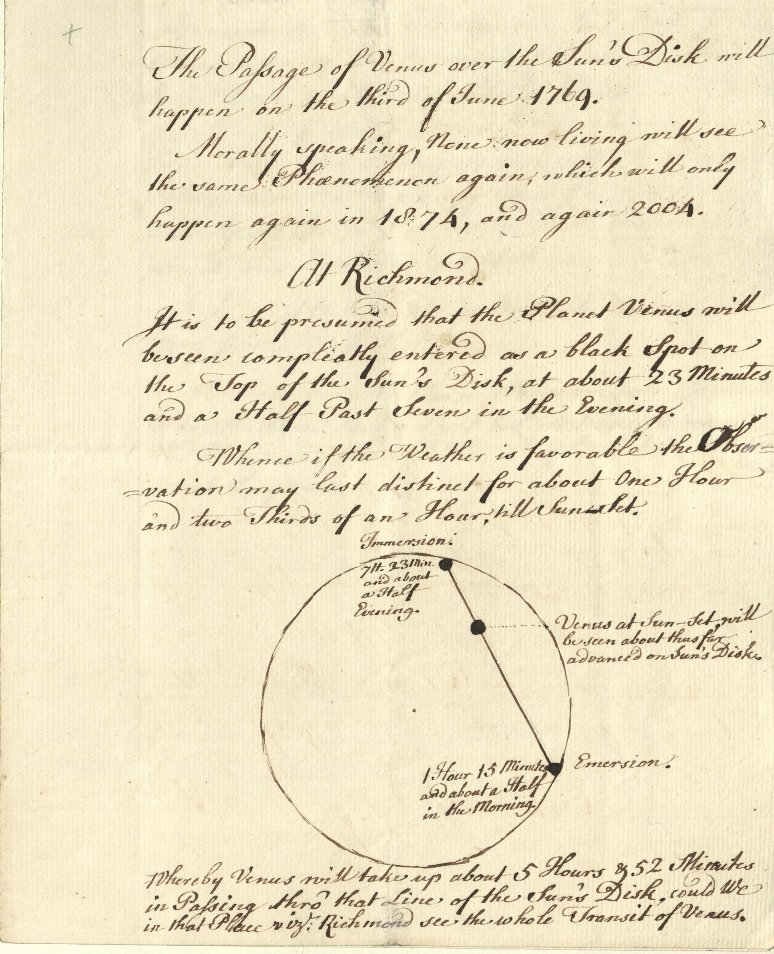

14. The Transit of Venus: George III at the forefront of Enlightenment science

Memorandum on the transit of Venus across the sun, June 1769?

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/895

Click on image to read in full and high definition. Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

This memorandum by Stephen Demainbray, the King’s Astronomer at Richmond, demonstrates King George’s interest in the cutting edge science of his day.

British astronomy was at the forefront of improving understandings of the place of the world in relation to the solar system and the wider universe. It also underpinned the more ‘high-tech’ practices of navigation at sea. The transit of Venus across the face of the sun is a rare but regular astronomical phenomenon, which afforded the opportunity, when comparing accurately recorded results from widely different locations, to calculate better the distances between the Earth, Venus and the Sun, and thus the size of the solar system.

This document contains several significant elements. Discussion of observations from the Pacific South Sea Islands reflect the decision, with King George’s funding, to send Captain Cook to Tahiti in 1769; his exploration of Australia was his secret secondary mission after fulfilling his astronomical tasks.

The reference to the exploitation of the long daylight hours of northern latitudes reflects the cosmopolitan efforts which were required to build up a sufficient number of observations. Other observations were made at various points across the Russian Empire, in Norway, Canada, the United States, Mexico and Baha California. On the other hand, the extended discourse on the expected view from Richmond is there because of the King’s own personal enthusiasm and interest, for he had recently had built a new observatory in the deer park at Richmond Palace, from which he took his own measurements of the transit of Venus.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

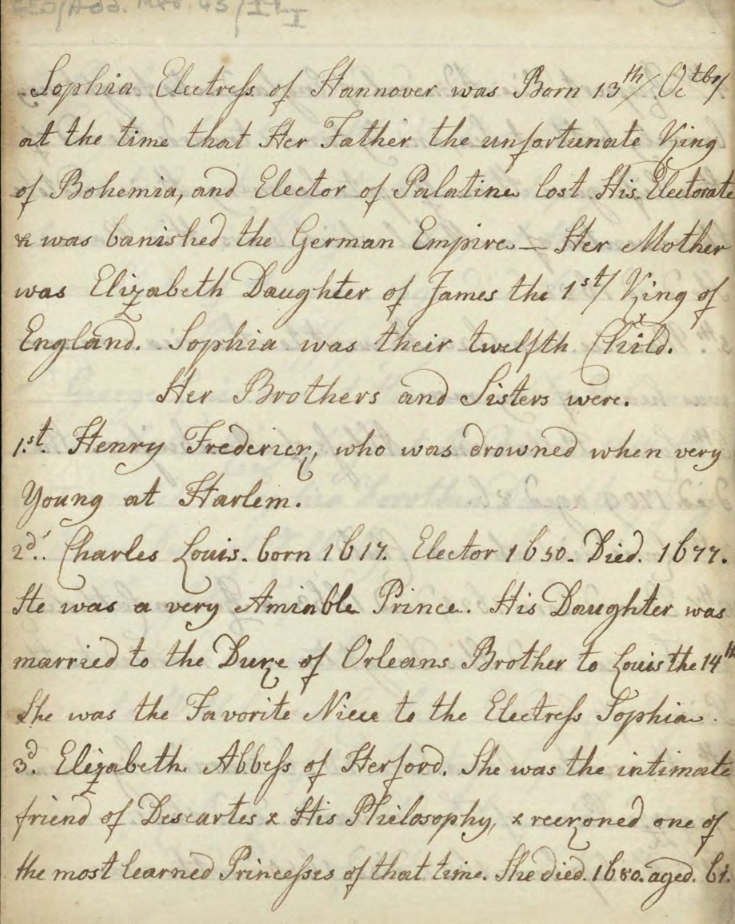

15. Lineage and legitimacy

Queen Charlotte’s notes on the life of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, undated.

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/43/19i

Queen Charlotte was the consort of George III. By many accounts it was a happy and successful marriage, made more difficult by the king’s stuggle with mental illness late in his life. Together they had 15 children. The queen was interested in music, literature, and botany, and fluent in English and French as well as her native German. She cultivated her daughters’ artistic and intellectual interests, bringing women into the royal household such as the famous novelist Frances Burney, who spent four years at court. The queen also established a printing press at Frogmore House, her private residence on the grounds of Windsor Castle.

Queen Charlotte’s materials in the Royal Archives include these notes on the negotiated succession that eventually brought her husband to the throne. King George III was the third of the Hanoverian kings, as part of the succession agreement in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The Hanovers were related not to the monarchs who immediately preceded them, Queen Anne and King William and Queen Mary, but through George I’s mother, Sophia, the granddaughter of James I, to the seventeenth-century Stuarts.

Queen Charlotte wrote out at least these three copies of the lines of descent beginning with Sophia, the Electress of Hanover. She specifies important details of births, marriages and deaths, and birth order, but the queen also included details, seeming to emphasize the interests and virtues of some of the women in the family’s history. She noted the intellectual pursuits of two women in this lineage, Elizabeth the Abbess of Hertford, ‘the Intimate Friend of Descartes & His Phy-losophy & reckoned one of the most learned Princesses of that time’ and ‘Willhelmina Caroline Princess of Anspach a great Favorite of the Electress Sophia & a Scholar of Leibnitz’.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

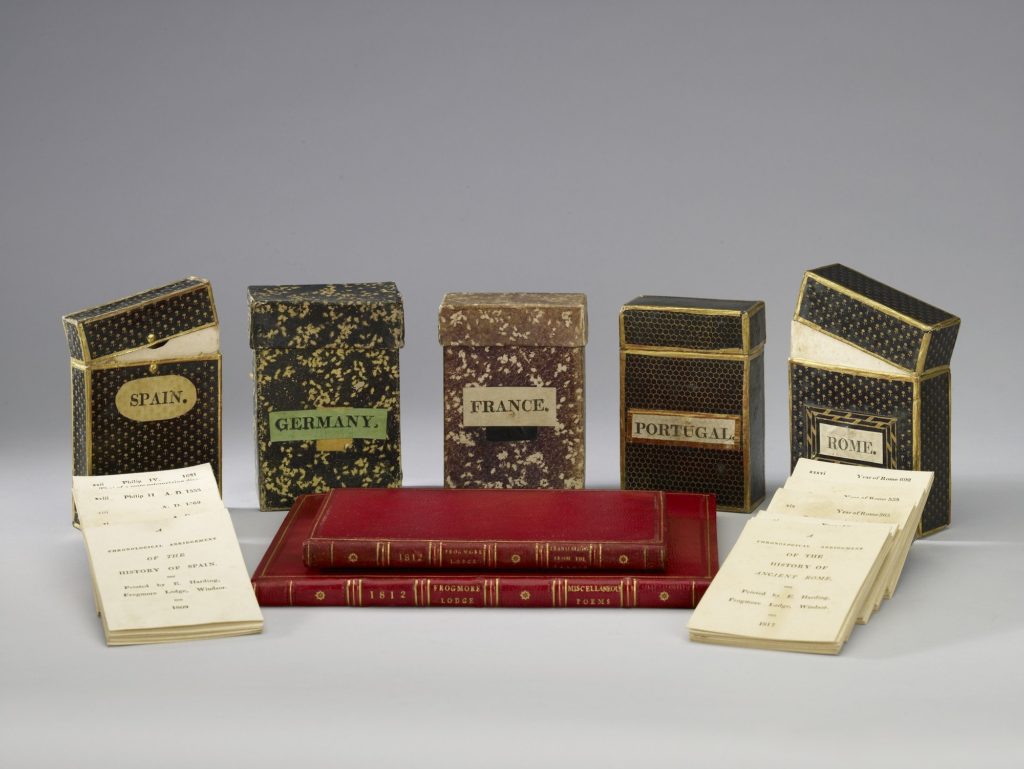

16. Women’s Educational and Literary Culture

The ‘German Empire’: Manuscript of published text of A Chronological Abridgement of the history of Germany printed by E Harding at Frogmore Lodge, written on individual cards.

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/43/20/1-2

Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 1128954, E Harding, A Chronological Abridgement of the History of Germany (Frogmore, 1810) (c) Her Majesty the Queen

Queen Charlotte’s interest in literature and arts extended, as did her husband’s, to the material objects of learning. The establishment of a printing press at Frogmore House, her retreat on the grounds of Windsor Castle, is one important example.

These extraordinary curriculum cards, printed at Frogmore House and then housed in boxes probably created in the royal bindery at Windsor, show the lively literary and educational circles Queen Charlotte gathered at court for her own benefit and enjoyment, and for the education of her daughters. There are two related set of objects, the manuscript (handwritten) version of the cards, and then the printed sets. A full set of manuscript cards exists only for two of the printed sets. Seen here is one of the manuscript cards for the German Empire, with the accompanying box. Surely there would have been earlier, rougher drafts, and it may be that in the course of the Georgian Papers Programme we will discover more about the sources that the Queen, the Princesses and their ladies at court used to compose them.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

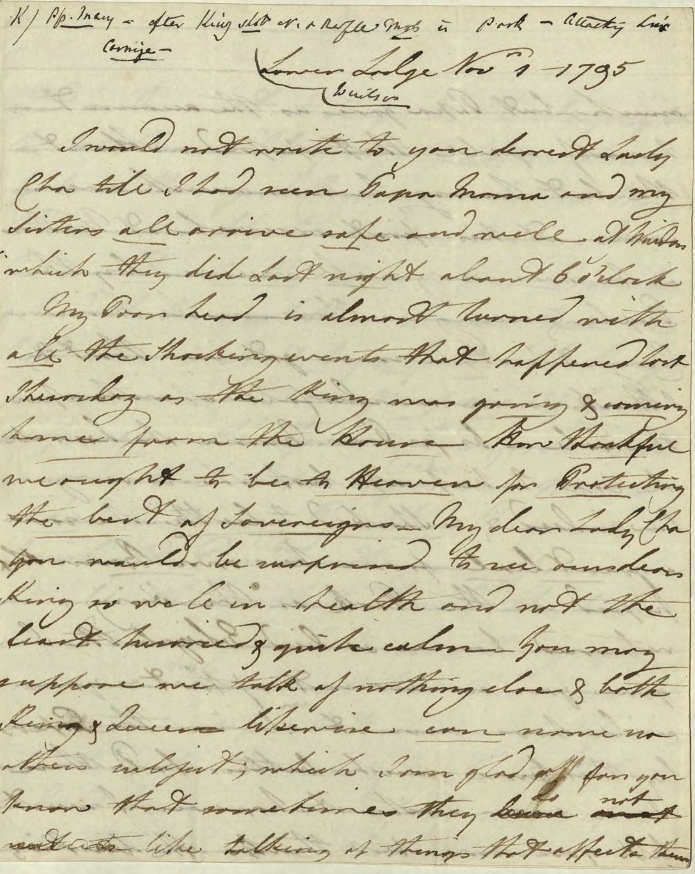

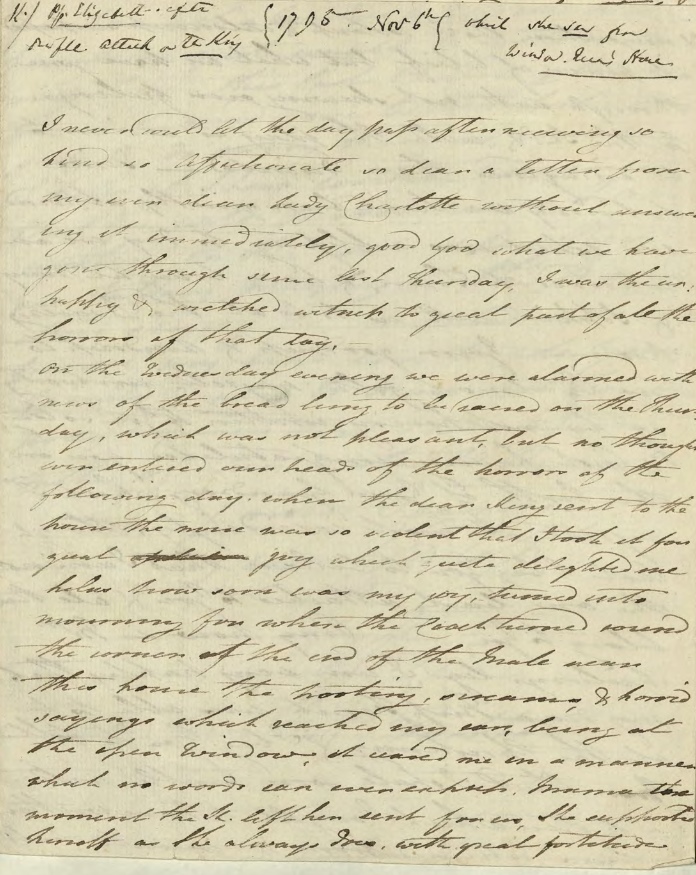

17. George III is attacked in his coach, 1795

Letter from Princess Mary to Lady Charlotte Finch, 1 November 1795

Letter from Princess Elizabeth to Lady Charlotte Finch, 6 November 1795

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/15/8167-8

Click on image to read in full and high definition Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

Click on image to read in full and high definition. Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website

On 29 October 1795 George III was attacked by a mob as he travelled by carriage to the state opening of parliament. The glass of the carriage window was pierced, either by a bullet or a stone. This was one of several occasions on which the king’s life was genuinely imperilled (there were also serious assassination attempts in 1786 and 1800).

These letters, written by Princesses Mary and Elizabeth to their former governess, Charlotte Finch, recount the immediate reaction of the King’s family to the incident – no doubt in the back of their minds was the fate of the French royal family in the Revolution.

Several things emerge clearly – not least the genuine love of their children for the king and queen, demonstrating that the famous domesticity of this family was more than a myth. The letters also reveal George’s personal courage in moments of crisis, but also the strong emotions that such incidents evoked in both him and his consort; and the importance of his belief in divine providence, ‘Man proposes and God disposes’, in enabling him to absorb severe blows as varied as the deaths of his children, the loss of America, and attempts on his own life.

Difficult to read? Click here for a typescript of the letters.

18. A Global Monarchy

Princess Sophia (1777–1848), A map of the world containing the discoveries of Capt. Cook, 1792 Pen and ink and watercolour, edged with green silk

RCIN 711056

No image as yet available.

In addition to the history cards written and printed at Frogmore House (above), the Royal Archives includes other examples of a global perspective. Despite the loss of the North American colonies, Britain’s global empire was expanding at the end of the eighteenth century. It is not surprising that a keen attention to geography, and to Britain’s role in the world, was evidenced by the entire royal family.

In 1768 George III commissioned Captain James Cook to undertake a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the South Pacific in part to observe the Transit of Venus (see Item #14) from Tahiti. He also mapped large swaths of the Pacific, including Hawaii, the eastern coast of Australia, and New Zealand, almost all entirely new to Europeans. It was to be the first of Cook’s celebrated voyages, which captured the attention of the British public and of George III’s household.

Princess Sophia, the fifth daughter of George III, drew this map when she was just 14 years old, demonstrating not only the enthusiasm for Cook’s explorations, but the extent of her education in geography, current events, and the arts. The governess of George III’s daughters, Lady Charlotte Finch, had taught them using among other educational materials prints and jigsaw puzzles.

On the map the Princess has carefully traced the routes of Cook’s ships the Endeavour (1768–71) in yellow and of the Resolution (1772–5 and 1776–9) in pink. The Resolution is shown at full sail in the Pacific.

See the catalogue entry on the Royal Collection Trust Website.

END OF THE EXHIBITION

Thank you for visiting the Georgian Papers virtual Hamilton exhibition.

If you have enjoyed the Exhibition and would like to follow the progress of the Programme, you can keep track of this exciting project by joining the King’s Friends. Membership is free, and Friends receive regular newsletters (find out more here): you can find the sign up page here. Why not follow us on Twitter, where we often post new discoveries or project news! And if you found the handwriting in these documents an enjoyable and challenging puzzle, there will shortly be opportunities to join in the task of transcribing some of the remaining 400,000 pages to make them more accessible to all. Again, follow us on Twitter to learn more.

You can read a series of our reflections on Hamilton and its staging in both London and the United States in two blogs on The Georgian Papers Programme website:

George III in London: What Hamilton Tells Us About the King’s Role, by Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf

‘Awesome, Wow’: King George III in the American Popular Imagination, by Karin Wulf

All images supplied by the Royal Archives and (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2016-18.

Exhibition Credits

Hosts for the Exhibition:

For the Royal Archives

Oliver Urquhart Irvine The Queen’s Librarian and Assistant Keeper of the Royal Archives

Bill Stockting Archives Manager, Royal Archives

Oliver Walton Georgian Papers Programme Coordinator, Royal Archives

Carly Collier Assistant Curator of Prints and Drawings, Royal Collection Trust

Sarah Davis Head of Media Relations, Royal Collection Trust

Katie Buckhalter Assistant Press Officer, Royal Collection Trust

Ben Fitzpatrick Photographer, Royal Collection Trust

Academic Directors for the Georgian Papers Programme

Arthur Burns Kings College London

Karin Wulf Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, William & Mary

Virtual and physical exhibitions devised and compiled by

Arthur Burns Kings College London

Karin Wulf Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, William & Mary

Oliver Walton Georgian Papers Programme Coordinator, Royal Archives

Technical assistance: Sam Callaghan, King’s College London, and Sara Belmont, William & Mary

Drawing on research, assistance and commentaries by the entire Georgian Papers Programme team of archivists, historians and cataloguers.

More information about the Programme can be found on this website.

More information and the currently digitized material can be found on the Royal Archives site: royalcollection.org.uk/collection/georgian-papers-programme