William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, by Richard Crosse. RCIN 420120 ©

The newly digitised papers of William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh provide a fascinating glimpse, predominantly through correspondence, into the Duke’s private life and role as George III’s unofficial ambassador. The featured letters, principally sent from the Duke to his brother, George III, and his nephew, George, Prince of Wales (the future George IV), reveal the absorbing dynamics of their relationships and events which shaped these bonds.

In addition to correspondence, the papers include three account books which provide an insight into the Duke’s military career in the 1st, 3rd and 13th Regiments of the Foot (predominantly referenced in the military agent Cox and Drummond’s account book). The volumes also detail the Duke’s household expenses, charitable donations, and refer to other offices he held, including that of Ranger of Hampton Court Park.

Prince William Henry, the third son and fifth child of Frederick, Prince of Wales and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, was born on the 14th November 1743, and in 1764 was bestowed the titles of Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, and Earl of Connaught. When George III became King, the Duke travelled the continent extensively on his behalf to visit royalty and the nobility. Reporting regularly, his travels are well documented within the papers, and heavily feature his sisters, Augusta, Duchess of Brunswick, and Caroline Matilda, Queen of Denmark and Norway. His remarks, when visiting them in their respective territories, highlight the difference between his relationship with his eldest and youngest sisters. Visiting Queen Caroline Matilda at the Danish Court in 1769 he writes sympathetically, ‘I left the poor Queen in very low spirits’, but this affection for his youngest sister does not extend to Augusta whom he obviously distrusts, describing her ‘as gossiping as ever’, while believing she only ‘pretended to be very glad to meet again’ (GEO/MAIN/54305-54306). However one of the Duke’s most interesting encounters took place at Genoa in 1771, when he met his distant relative, Charles Edward Stuart (otherwise known as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’), who had returned from the Antibes. He writes ‘the Pretender’ was ‘curious to know who we were…at the corner of the street we stumbled upon each other, he pulled his hat off civilly, and rather gave way, and turned to his companions smiling’.

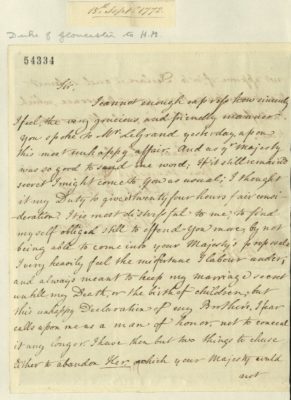

The Duke of Gloucester writes to George III on the subject of his secret marriage, 1772. RA GEO/MAIN/54334 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

It appears from this early correspondence between George III and the Duke of Gloucester that the brothers were close, but the revelation in 1772 that the Duke had secretly married Maria, Dowager Countess of Waldegrave, in September 1766, significantly strained their relationship. The Duke claimed the marriage was hidden out of respect for the King, and only confessed to the union when his wife was expecting their first child. As this took place after the passing of the Royal Marriages Act of 1772, (which would invalidate any subsequent union lacking the King’s consent) an enquiry into the marriage’s validity was undertaken to ensure the legitimacy of their children. In spite of the nuptials being duly validated, George III showed his displeasure with his brother’s actions by refusing to see, speak of, or provide for the Duchess, and as a result the brothers’ correspondence almost ceases, with the Duke’s role as an unofficial ambassador coming to an end. Unhappy with this state of affairs, the Duke appealed to his brother for forgiveness in 1775, writing that although this act had displeased the King, ‘the laws of God have not made, & the laws of the land had not then made criminal’. The estrangement appears to have lasted until 1780 when the King, softening his position, notes that he wished to be on good terms with his brother and would happily meet his children, but steadfastly refused to discuss the Duchess.

In spite of a reconciliation between the brothers their correspondence never returns to the informality once shared, but this does not mean later correspondence lacks the Duke of Gloucester’s more intimate thoughts. A new correspondent features from 1780, his nephew George, Prince of Wales, and the Duke’s candour not only provides a fascinating insight into the two men’s relationship but also the strained relationship between the Duke and the King. The contrast between letters sent to the King and the Prince of Wales is marked. The Duke, often writing to both on the same day regarding the same subject, is formal, respectful and displays his subservience to the King, whereas with the Prince of Wales he is informal and reveals personal details. These intimate details not only relate to the Duke’s life but that of the young Prince and how his nephew was perceived by others. One example of this is found within a letter dated 1785 in which the Duke, upon hearing that the Prince was not attentive to his health and was ‘amusing [him]self much’, warns him to balance his health with pleasure, words that if heeded may have prevented the ill health which plagued the Prince’s later life.

Maria, Duchess of Gloucester by Ozias Humphrey. RCIN 420967 ©

The correspondence to George, Prince of Wales reveals further insights, particularly in relation to Maria Fitzherbert, whom the Duke informs the Prince ‘I am convinced she loves you far beyond herself’. The Duke appears to have been fond of Maria Fitzherbert, evidently corresponding with her himself, and genuinely enjoyed her company, writing that she is an ‘amiable character’, and that he had ‘on some unfortunate occasions’ been pleased to offer her public civility in Geneva in 1785 to make her ‘long exil[e] as bearable as I could’, a sign she may have been ostracised (GEO/MAIN/54372).

The Duke of Gloucester’s letters to the Prince also reveal his own marriage was not a happy union. The divisive marriage had produced three children: Princess Sophia Matilda, Princess Caroline (who died of smallpox in childhood) and Prince William Frederick, but writing in 1787 he states that his wife’s ‘unfortunate turn of mind and temper’, and ‘evil representations to them on every possible subject makes it absolutely necessary for me to put them quite out of her hands!’ To resolve the situation the Duke sought George III’s permission to separate his beloved children from the Duchess, consequently sending Prince William to Cambridge University and engaging a governess for Princess Sophia. In spite of their mother, the Duke seems to have found genuine happiness in his children, writing to his son in 1804 that the bond between the Prince and Princess Sophia was ‘the greatest blessing & comfort to me’.

It is thought the Duke of Gloucester fathered another (illegitimate) child, Louisa Maria La Coast, with his mistress Lady Almeria Carpenter (the Duchess of Gloucester’s Lady in Waiting briefly mentioned in the letter GEO/MAIN/54374-54375), and it is probable this affair contributed to the breakdown of the Duke’s marriage. Once the Duke returned to Britain in 1787, although his union had ended in all but name, the Duchess resided with him, and Lady Carpenter, at Gloucester House until his death on the 25th August 1805.