Copy of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of George IV c.1822-1830 ©

In addition to George IV’s Calendar of official papers there is a modest collection of his private papers held within the Royal Archives. The majority of these records date from the time of his reign, 1820 to 1830, with the exception of his executor’s papers which end in 1837 when the majority of his estate had been settled.

These papers have been catalogued within the following three series:

Letterbook of George IV’s Correspondence

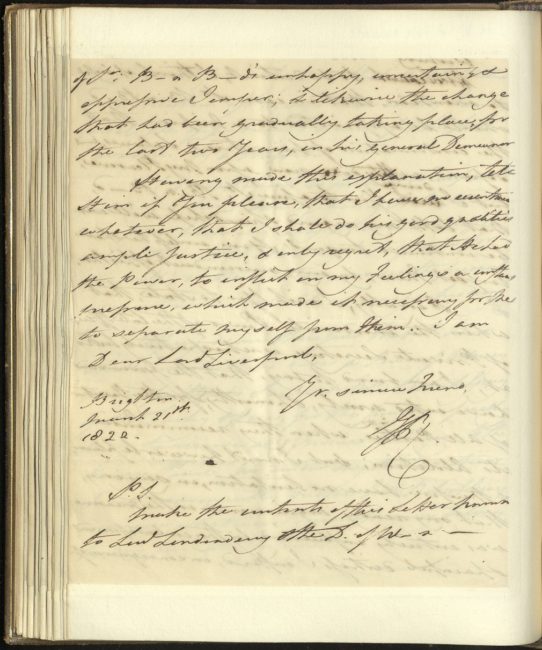

Copy letter from George IV to Lord Liverpool concerning Benjamin Bloomfield, March 1822. GEO/MAIN/24954-55 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The majority of George IV’s surviving personal correspondence was at some point during the 19th century bound into this single volume. The diverse nature of the compiled correspondence covers not only private matters but also foreign affairs and political events, such as Queen Caroline’s threats to attend George IV’s coronation in 1821 (GEO/MAIN/24920-24923); the Treaty of Adrianople, 1828 (GEO/MAIN/25032); and Lord Goderich’s opposition to the Corn Bill, 1827 (GEO/MAIN/25015-25016). Letters from foreign royalty feature prominently (including Tsar Alexander I), as do lengthy communications relating to the abolishment of the position of Private Secretary and the dismissal of Benjamin Bloomfield. The correspondence regarding Bloomfield is an anomaly within this collection as it reveals the King’s thoughts regarding his Private Secretary. He describes Bloomfield as having an ‘unhappy…& oppressive temper’ which he regretted ‘had the power, to inflict in my feelings a constant pressure which made it necessary for me to separate myself from him’ (GEO/MAIN/24954-24956). The reason for this general lack of insight into the King and man that George IV was, is due to these records predominantly being written to, rather than by, him. To gain a greater understanding of the context surrounding the creation of these letters they should be consulted alongside George IV’s official correspondence (yet to be published for these dates), and his papers located within other collections.

The volume’s contents is not its only intriguing aspect as its custodial history is equally noteworthy. Unlike the majority of the Georgian Papers deposited at the Royal Archives the letterbook did not arrive with the deposit from Apsley House, but was presented to the Archive in September 1905. It had been in the possession of Princess Beatrice, the youngest daughter of Queen Victoria, who had inherited the late Queen’s papers amongst which she discovered the volume. Why these selected letters (but not others) were in the possession of the Royal Family after George IV’s demise and carefully bound together is at present unknown. It possibly relates to the fact that contained within the volume are letters from Queen Victoria’s own mother, the Duchess of Kent, regarding Victoria’s childhood and her sister Feodora’s marriage (GEO/MAIN/25020-25026). The future discovery of the volume’s complete custodial history, and its elusive location prior to Queen Victoria’s reign, could enrich the interpretation of the contents.

George IV’s Executors Papers

Upon the death of George IV it fell to his executors, Sir William Knighton and the 1st Duke of Wellington to settle his estate and fulfill the late King’s extensive financial obligations. This series comprises the letters, outstanding bills and receipts created and used to carry out this duty. The information these can reveal, although limited, provides a tantalising insight into George IV’s life and spending habits other records may not disclose. Amongst the usual records for paintings, building work and unpaid tradesmen’s bills, there are an eclectic mix of financial documents relating to matters from health and marriage treaties to the care the King’s menagerie.

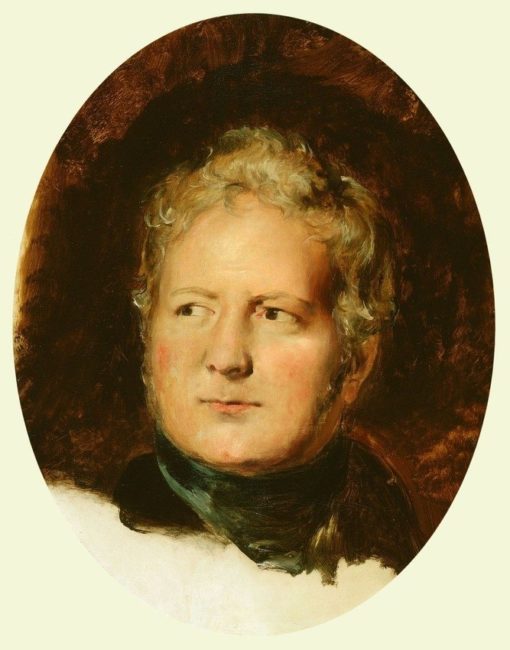

Sir William Knighton by Sir David Wilkie, c.1824-5 ©

Some of the most revealing documents regard George IV’s health. His surgeon and apothecary’s account (GEO/MAIN/32817-32822) details the extensive treatments the King received in the last years of his life, and an account for dental bills, although lacking treatment details, intriguingly reveals the frequency of his visits.

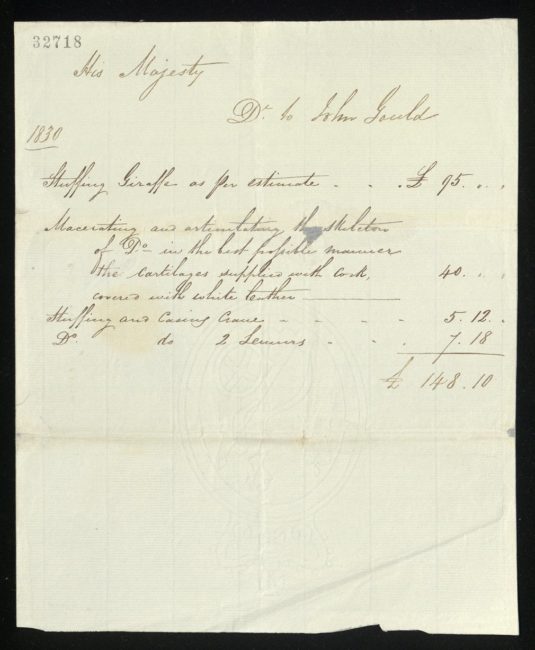

Various other noteworthy documents include a taxidermy bill for the stuffing of a giraffe (probably the same animal presented to George IV in 1827 by Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt), and the payment of Frederick William III, King of Prussia, under the terms of the marriage settlement of Frederick, Duke of York and Princess Frederica of Prussia.

In addition to the extensive accounts settled by George IV’s executors there are numerous cases of claims refused due to the inadequate evidence presented. Many of these, such as those written by George IV’s menagerie manager Edward Cross, claimed expenses which could not be evidenced (such as deliveries and receipts received elsewhere), which presents the possibility that this was a regular occurrence. If this was the case, were the King’s prolific and notorious spending habits far greater than previously thought and many bills simply unrecorded? Deeper research of the Georgian Papers could reveal a truer understanding of George IV’s finances.

Account from John Gould for stuffing a giraffe and other animals, 1830. GEO/MAIN/32718 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

George IV’s Miscellaneous Private Papers

This series comprises various miscellaneous papers kept separately from George IV’s private or official documents, but it is not entirely evident as to how, or why, many of these came to be within the collection.The papers within this small series contain a variety of topics from an account of George IV’s excruciating final hours, by the ophthalmologist Sir Wathen Waller, to a letter from the Reverend William Buckland to Sir William Knighton, c.1823, referencing an ‘extraordinary fossil monster’ and the bones of a ‘gigantic reptile’. Buckland’s letter draws attention to the contemporary fascination for natural history and the fact that these discoveries were so tantalisingly new they had not even been assigned the names by which they are known today. The ‘fossil monster’ is almost certainly the Plesiosaurus discovered by Mary Anning at Lyme Regis (purchased by the Duke of Buckingham), and the ‘gigantic reptile’ is most likely to be the Megolasaurus discovered near Blenheim.

Interestingly the will of Olive Serres (who alleged to be the illegitimate daughter of Henry, Duke of Cumberland, and styled herself as Princess Olive of Cumberland) appears within these papers, and the presence of this document within the collection possibly indicates her case was strong enough to be taken seriously by the royal family. A point worth noting within the will is her claim to possess papers relating to George III’s marriage, which she instructs to be sold upon her death. If she did in fact possess these papers their fate is unknown, but future analysis of the Georgian Papers could reveal further details.