Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751) c.1720-3 ©

Born in Hanover in 1707, Frederick was the eldest son of George II and Caroline of Ansbach, and as such destined to become king of England after his father’s death. Having been left behind in Hanover (as a representative of continued authority) when the rest of the Royal Family moved to England in 1714, Frederick first arrived in England only a year after his father George II became king and later assumed the title as Prince of Wales in 1729. At this point Frederick and his parents had not seen each other for around 14 years; this physical distance may well have been the origin of the tensions that characterised the relationship between parents and son.

Bootle papers

Around a dozen letters in this volume kept by Sir Thomas Bootle relate to a notoriously critical moment in the already troubled relationship between the Prince of Wales and his parents, George II and Queen Caroline: the circumstances surrounding the birth of Frederick’s first child, Augusta Frederica. Having lied about his wife’s due date, Frederick secretly moved the mother-to-be from Hampton Court Palace to St James’s Palace as soon as labour began. In doing so, Frederick was actively preventing George II and Queen Caroline from attending the birth, a breach of royal protocol in which royal births were witnessed by members of the Royal Family and senior courtiers to guard against supposititious children. In these papers, the King and Queen clearly express their disappointment at the Prince’s behaviour and make clear that the christening of the baby will follow the normal procedure: it will be performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King and the Queen will be, respectively, godfather and godmother. The tone of these messages is very tense and suggests a rift in the family relationship that ultimately never heals; another copy of this exchange is in George II’s papers.

The Bootle papers also reflect Frederick’s keen interest in politics and elections. As Prince of Wales, Frederick went about establishing his own court in opposition to that of George II in much that same way that his own father had done in the time of George I, and his grandson the future George IV would go on to do during the reign of his father, Frederick’s son, George III. In a letter to Sir Thomas dated June 1747, Frederick justifies his actions writing:

My upwright Intentions are Known to Y[o]u, my duty towards my Father calls for it, one must redeem him, out of those Hands, that have sullied the Crown, and are very near to ruin all

GEO/MAIN/54059-54060

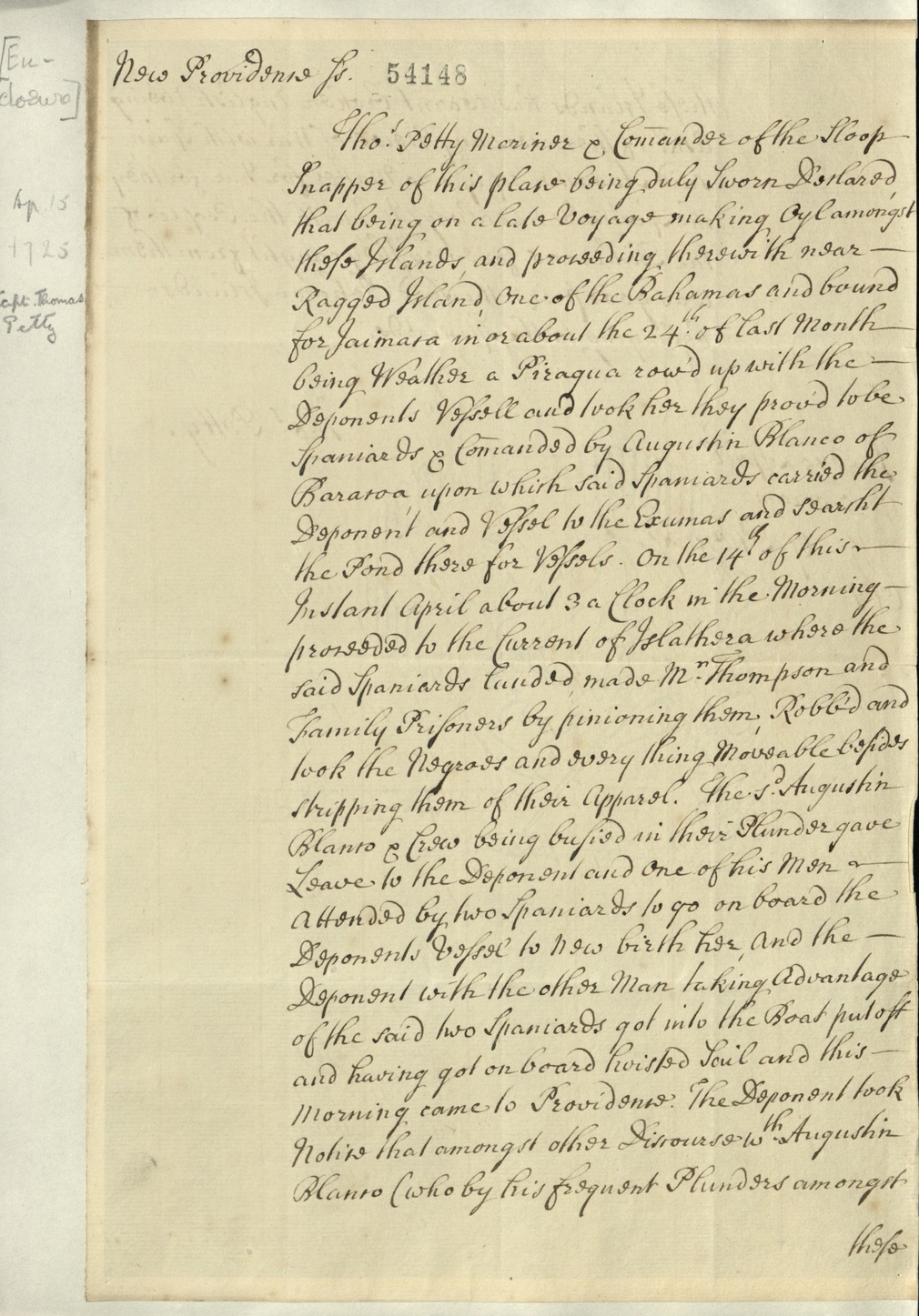

Captain Thomas Petty’s deposition recounting the capture of his ship, the Snapper, by Spanish pirates, 1725. GEO/MAIN/54148 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Military and foreign affairs

Another set of papers contain notes on the navy and the military of both Britain and foreign powers. The largest bundle of these contains copies of documents submitted to the House of Lords in 1729 and relates to depredations made by the Spanish on British subjects in the Caribbean. These include a deposition by Captain Thomas Petty, commander of the Snapper, of how his vessel was captured by the notorious pirate Augustin Blanco who then with his newly captive crew ‘proceeded to the Current of Islathera [Eleuthera] where the said Spaniards landed, made Mr. Thompson and Family Prisoners by pinioning them, Robb’d and took the Negroes and every thing moveable besides stripping them of their Apparel.’ Due to Blanco’s complacency, Petty and his crew were able to escape to the island of New Providence but in his closing comments, Petty notes a conversation with Blanco that highlights the Anglo-Iberian power struggle that is being played out in the Caribbean at this time: ‘askt if there was any News of War with Spain said Augustin reply’d, no matter for War for they the Spaniards had always War with the People of the Bahamas for every thing they caught from them was good prize’.

In October 1745, the Jacobite threat was still present and the ‘rebels’ were very close to Edinburgh. Writing in his capacity as Envoy Extraordinary, Robert Trevors requests permission from the States General to allow Prince William, Duke of Cumberland and his troops pass from Antwerp to Willemstat via Klundert without delay, ‘le moindre delay dans leur Route peut entrainer des suites très préjudiciables au service qu’on s’en propose‘, pleading ‘par leur Religion et par Leur Liberté‘ [‘the slightest delay in their route could lead to very detrimental consequences to the service for which [the troops] are intended’ pleading ‘by their religion’ and ‘by their liberty’]. The Jacobite threat was ultimately crushed at the Battle of Culloden in April of the following year with only moderate losses on the side of the ‘Conquering Hero’, the Duke of Cumberland – albeit known to many hereafter as ‘The Butcher’. While the losses on the Hanoverian side were small, around 1000 soldiers are estimated to have been injured and a subscription scheme was set up to provide relief for the widows and veterans who fought to defend the Hanoverian claim.

Personal papers

A small selection of personal letters written by Frederick to his children, George and Edward, may also be found in this collection. These show a caring father who is deeply involved in his childrens’ education and worries for their health – and many a remonstration for not writing frequently enough! Frederick appears to have seen himself not just as a father to his sons but also as their friend and mentor. In this letter, probably dating from 26 September 1747, Frederick comments on the conduct of General Cronström during the siege of Bergen op Zoom. Cronström was said to have been asleep during the French attack and, despite being governor of the town, escaped while the fighting was still on-going. Frederick agrees with George’s assessment (the contents of which are not known) adding:

There are great dangers Officers must venture, death is the least, as they may be one unlucky Step, loose their Reputation, and be a Curse to their Country…That none of You my Dr Boys, may ever forget Your duty, but allways be a Blessing to Yr Family, and Country, is the prayer of Yr best friend, and Father, Frederick P.

GEO/MAIN/54226

The Children of Frederick, Prince of Wales 1746 by Barthélemy de Pan (1712-63) ©

These papers also include the extraordinary Instructions for my Son George which contains advice on a range of subjects from war and the national debt, Hanover, and personal and kingly conduct. Written in 1749, just over 2 years before Frederick’s untimely death, the Instructions attain a sad premonitory quality when we read: ‘I shall have no regret never to have wore the Crown, if you do but fill it worthily’. It is easy to imagine the impact this document had on the young George in the months and years after his father’s death but much less clear is how frequently he referred to them in his later years and the ultimate impact they had on his kingship.

As eldest son of George II, Frederick was heir apparent to the throne but his sudden and premature death aged 44 meant that the throne passed instead to Frederick’s eldest son, George III. Frederick died intestate which makes his draft will, probably in Sir Thomas Bootle’s hand, all the more interesting and poignant.

Augusta, Princess of wales (1719-72) ©

Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburh

Despite being the wife of the Prince of Wales and the mother of the future king, Augusta does not feature heavily in these records and there are only a handful of letters written by her. There are only two surviving letters in this collection from the Princess Dowager to her eldest son, George III (GEO/MAIN/54248 and GEO/MAIN/54249). Somewhat surprisingly both these letters are written in French perhaps suggesting that Augusta was more comfortable communicating – or at least writing – in French rather than English, which she had only learnt after her marriage aged 17. Somewhat less surprising is that there are so few letters between mother and son; an attempt by George II to grant the young prince George and his brother Edward their own establishment in 1756 was delicately rebuffed by George, aged 18:

I hope that I shall not be thought wanting in the Duty I owe Your Majesty, if I humbly continue to entreat Your Majesty’s permission, to remain with the Princess my Mother; this point is of too great consequence to my happiness for me not to wish ardently Your Majesty’s favour & indulgence in it

George II’s reaction to such defiance is not present among the Georgian Papers (if indeed it was ever recorded at all) but Augusta’s relief at the king’s approval is palpable in this copy or draft letter:

I beg leave to lay myself at [Your Majesty’s] feet, humbly hoping, yt Y.M. will suffer me; to return my most humble thanks, for Y.M. great goodness; in permitting my Son, to continue his residence with me; this gracious mark of Y. M. favour, makes me unspeakably happy; & fills my breast with ye warmest gratitude; there is nothing I more sincerly wish, than to convince Y. M. by every action of my Life; yt I am not entirely unworthy of ye confidence Y. M. is pleas’d to place in me

Augusta appears acutely conscious of the vulnerability of her position after the death of her husband leaving her alone in a foreign country with 9 young and adolescent children. In the few surviving letters to George II after Frederick’s death in 1751, Augusta seeks the protection of the king and signing off her letters emphasises her humility and obedience to her father-in-law, ‘La tres humble et tres obeissante servant sujete et fille Auguste’.

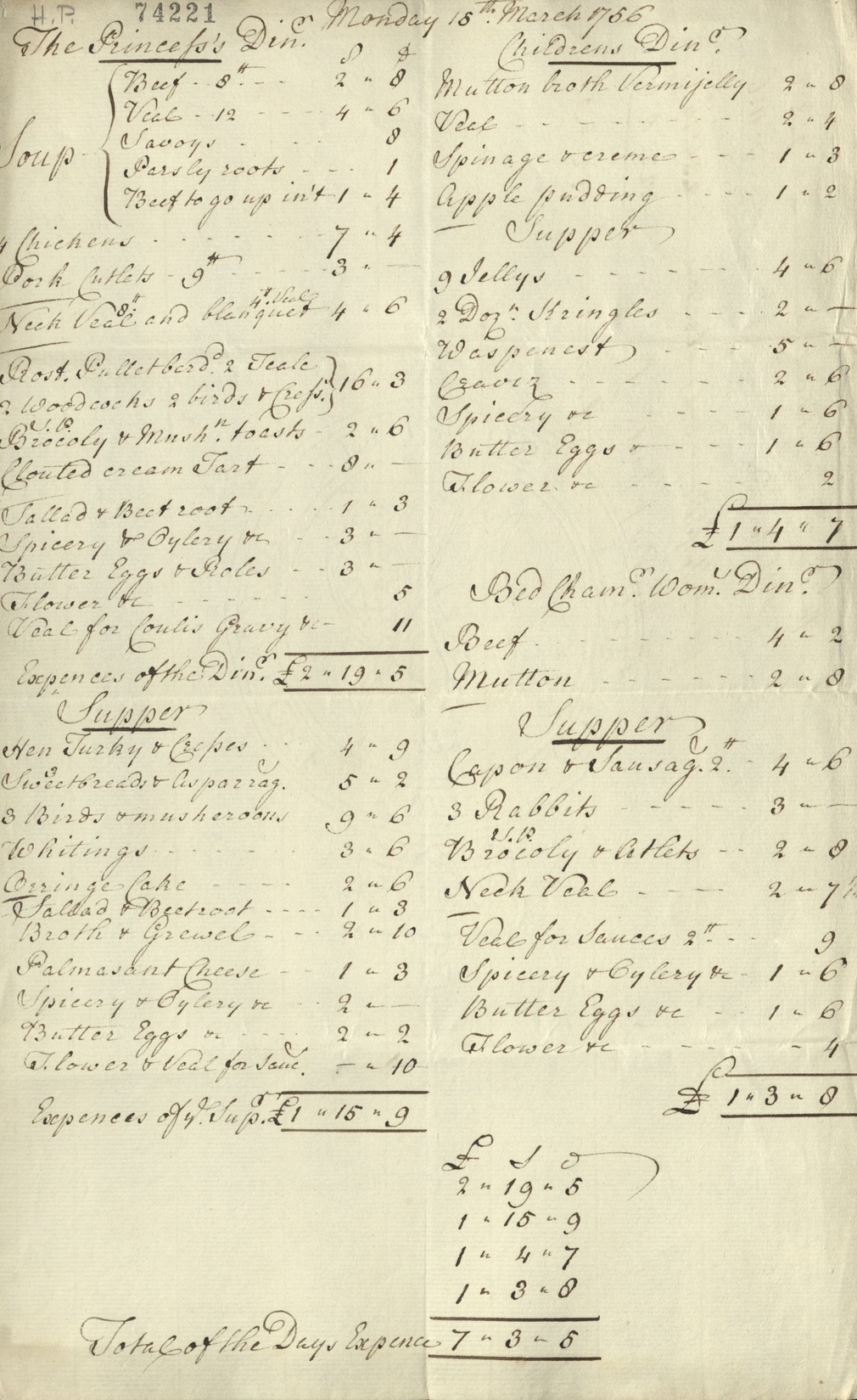

Cost of one day’s food for Augusta, Princess of ales, her children, and her Woman of the Bedchamber, 1757. Geo/MAIN/74221 Royal Archives /© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Many of the papers in this collection are written by officials on Augusta’s behalf after the death of Frederick. These papers were purchased in 1939 at the Hartwell House sale and could really be said to be the papers of Sir George Lee, Treasurer to the Princess Dowager, rather than Augusta’s own papers. Many documents concern the re-arrangement and management of the Household finances after the death of a husband whose debts totalled £78,500, approximately £9 million in today’s money! However, even Augusta’s expenditure appears to have outstripped her income. This account dated 15 March 1756 shows the daily cost of feeding Augusta’s young and growing family amounted to £7 3s 5d the equivalent of £836.62 per day! As John Grove, Clerk of the Kitchen, wrote, ‘Tis no easy matter to mannage the Kitchen and to do everything for Her Royal Highness Service’. He was, unsurprisingly, asking for a pay rise.

Accounts

The majority of Frederick and Augusta’s papers is made up of accounts. These bills and receipts provide a fascinating insight into Frederick and Augusta’s annual Household expenditure on goods purchased such as cutlery, stationery, fabric, liveries, books, jewellery and the like. Lists of medicines are also of particular interest not only for the information they provide on the Prince’s family’s health but also on common contemporary medical practice as we can see in this bill of 1747.

Works carried out at the Prince’s residences (Kew, Leicester House, Carlton House, Cliveden) can also be found in the bills. The focus on Kew Gardens demonstrates the great impact the Princess had in Kew’s redevelopment and the constructions of the Pagoda, the Orangery and the Temple of the Sun. Augusta began the Physic and Exotic Garden around 1759 with seeds, exotic plants, and trees being sent from abroad; by 1768 the herbaceous collection had over 2,700 species. The legacy of Augusta’s plant collection can still be seen today at Kew Gardens, planted in strict Linnaean order with each plant individually labelled.