Benjamin West, George III, 1779

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

The prospect of a duly elected successor to George Washington with the election of John Adams in 1796 raised important questions about how the succession of the executive might work in a fully elected government. In Hamilton, the king is famously dubious about Adams, and mentions having met him (which he did), though there are no papers we have yet discovered at Windsor related to Adams. One reason this transition was so poignant is that King George III, like all monarchs, also thought about succession, though with an entirely different considerations of how his reign would be affected by marriage, children—and his relationship with Parliament.

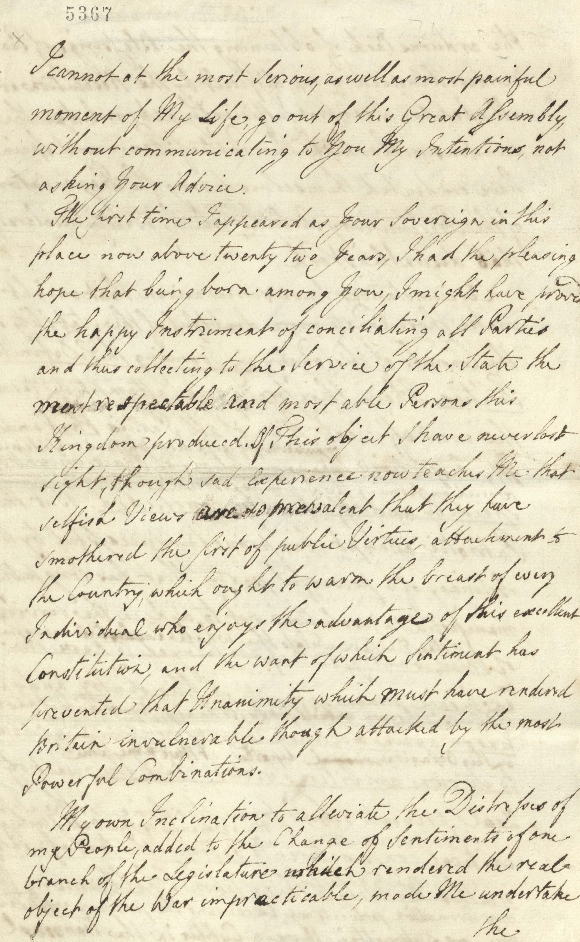

8. George III’s draft abdication speech, March 1783

Draft of a message of abdication from George III to the Parliament, 28 March 1783?

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/5367

This is one of the most remarkable documents among the official papers of George III in the Georgian papers. It is a draft speech intended for delivery to Parliament in which George III would renounce his throne in favour of his son, the future George IV, and retreat to his Hanoverian dominions (which he had never visited). George composed it because he was unable to find an alternative to accepting as his ministers Lord North and Charles James Fox, ‘men who I know I cannot trust’, following the collapse of his preferred options in the wake of the worsening of the situation in America. It was never delivered – and George had on other occasions threatened abdication – but it speaks eloquently to his state of mind in its agitated deletions, and is rich in ironies. It also speaks to George’s sense of his own failure to realise the ideal of a good monarch, and his belief that if God had ordained that failure, it was futile to resist it – even if it meant allowing prematurely on to the throne a son in whose abilities to rule well he was far from confident.

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

For a more detailed discussion of the significance of this document, see the blog by Professor Arthur Burns on the Georgian Papers Programme Website.

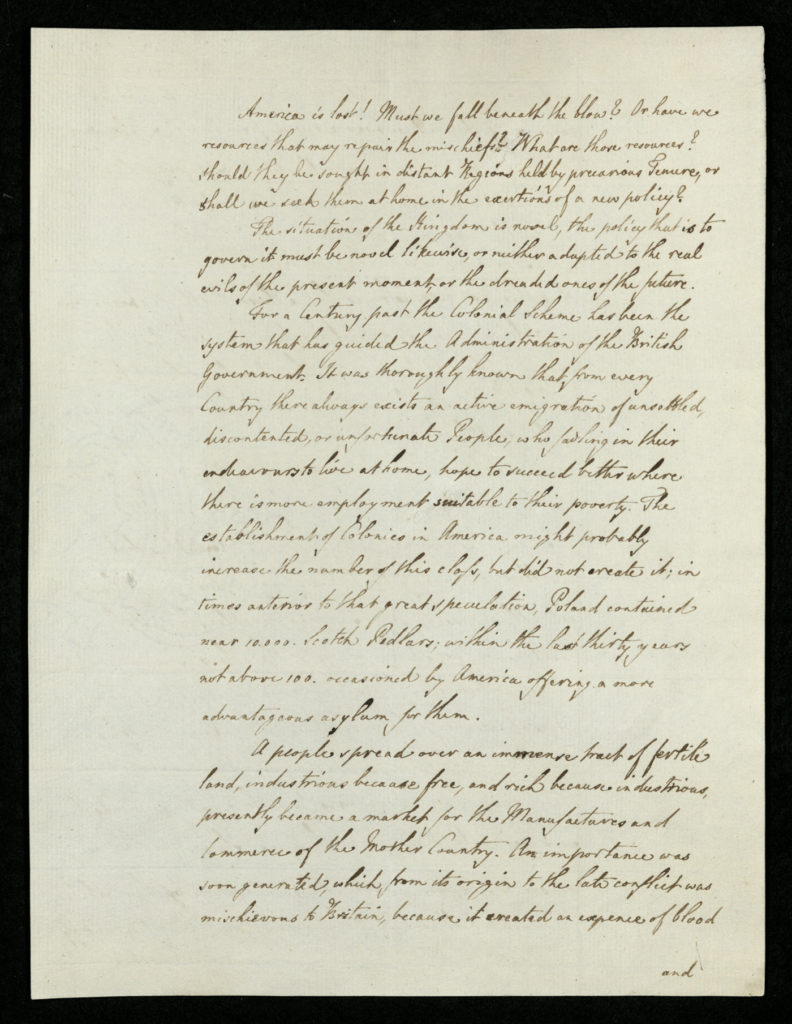

9. America is Lost!

Essay on America and future colonial policy [?1784]

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/2010-11

This essay is written in the hand of George III, but it was not his own composition. The passage looks to be a closely copied extract from a much longer essay published by the English agricultural writer Arthur Young in his magazine Annals of Agriculture, published in 1784, the year after the American Independence had finally been conceded. It is not merely a copy of the published article, though it may be a copy of an earlier draft. We know that George III corresponded with Arthur Young and even wrote for the Annals of Agriculture under the pseudonym of Ralph Robinson. It was most probably ‘commonplaced’ – that is extracted from the published version – and re-framed by the King as an exploration of the issues. In either case, the document offers a tantalising view of the King’s thoughts and feelings after the loss of the American colonies, and a remarkably optimistic view ahead.

This essay is written in the hand of George III, but it was not his own composition. The passage looks to be a closely copied extract from a much longer essay published by the English agricultural writer Arthur Young in his magazine Annals of Agriculture, published in 1784, the year after the American Independence had finally been conceded. It is not merely a copy of the published article, though it may be a copy of an earlier draft. We know that George III corresponded with Arthur Young and even wrote for the Annals of Agriculture under the pseudonym of Ralph Robinson. It was most probably ‘commonplaced’ – that is extracted from the published version – and re-framed by the King as an exploration of the issues. In either case, the document offers a tantalising view of the King’s thoughts and feelings after the loss of the American colonies, and a remarkably optimistic view ahead.

To read the whole of this document in high resolution, click on the image

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.

Click here to read the catalogue entry on the RCT website.

To learn more about the puzzle of this document, see two blogs on the Georgian Papers Programme Website, one by Dr Angel Luke O’Donnell, and one by Justin Clements.

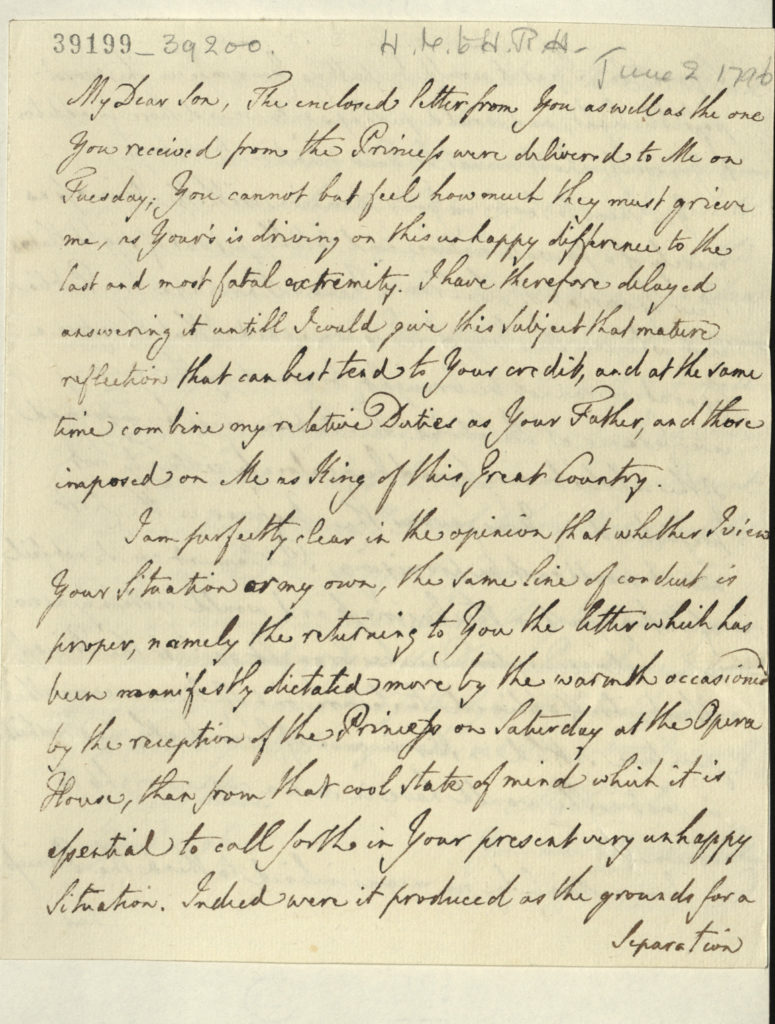

10. George III’s concerns about the Prince of Wales

Letter from George III to George, Prince of Wales, on the Prince’s wish to separate from Caroline, Princess of Wales, 2 June 1796

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/39199-39200

In 1796, at the same time as the young American republic was preparing to elect its 2nd president, George III had grave concerns about his own successor. This letter from George III to George, Prince of Wales, 2 June 1796 is about the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Princess Caroline of Brunswick, which was just over a year old. It was quickly proving a bad match, and the Prince wished to separate from his new wife. The king wrote that the Prince was governed more by the ‘warmth occasioned by the reception of the Princess of Saturday at the Opera House, than from that cool state of mind…‘ necessary in the situation. He advised that the Prince and Princess of Wales’ marriage is a public act, and that a separation may lead Parliament to secure the jointure settled on the Princess in case of the Prince’s death out of the Prince’s own income.

In 1796, at the same time as the young American republic was preparing to elect its 2nd president, George III had grave concerns about his own successor. This letter from George III to George, Prince of Wales, 2 June 1796 is about the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Princess Caroline of Brunswick, which was just over a year old. It was quickly proving a bad match, and the Prince wished to separate from his new wife. The king wrote that the Prince was governed more by the ‘warmth occasioned by the reception of the Princess of Saturday at the Opera House, than from that cool state of mind…‘ necessary in the situation. He advised that the Prince and Princess of Wales’ marriage is a public act, and that a separation may lead Parliament to secure the jointure settled on the Princess in case of the Prince’s death out of the Prince’s own income.

To read the whole of this document in high resolution, click on the image

Find it hard to read? Click here for a typescript of the document.