Holly Day is a PhD student in the department of History at the University of York funded by the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities, and an affiliate of the Centre for Eighteenth-Century Studies there. Her project considers the development of the pocket memorandum book in Georgian Britain, both as a print product and form of life-writing, with a thesis entitled ‘Memorandum Books, Markets, and Identities, 1748-c.1850’. She is supervised by Dr Hannah Greig and Prof. Mark Jenner. Prior to this she took a BA in History and Philosophy at the University of Exeter and an MSt in British and European History from 1500 to the Present at the University of Oxford. Her work for the Georgian Papers Programme was undertaken as a White Rose Studentship Researcher Employability Project, under which students complete a short project outside their home university away from their primary research area to gain experience of employing their doctoral-level skills in a workplace and to complete a specific piece of work for the host organization. The Project is very grateful to both Holly and the White Rose College for the opportunity to conduct this important project.

Holly Day is a PhD student in the department of History at the University of York funded by the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities, and an affiliate of the Centre for Eighteenth-Century Studies there. Her project considers the development of the pocket memorandum book in Georgian Britain, both as a print product and form of life-writing, with a thesis entitled ‘Memorandum Books, Markets, and Identities, 1748-c.1850’. She is supervised by Dr Hannah Greig and Prof. Mark Jenner. Prior to this she took a BA in History and Philosophy at the University of Exeter and an MSt in British and European History from 1500 to the Present at the University of Oxford. Her work for the Georgian Papers Programme was undertaken as a White Rose Studentship Researcher Employability Project, under which students complete a short project outside their home university away from their primary research area to gain experience of employing their doctoral-level skills in a workplace and to complete a specific piece of work for the host organization. The Project is very grateful to both Holly and the White Rose College for the opportunity to conduct this important project.

_____

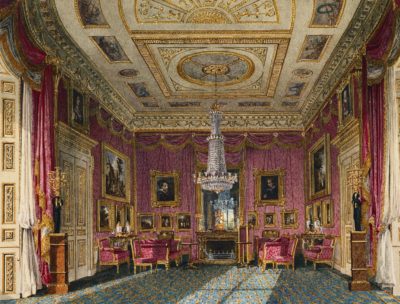

Charles Wild (1781-1835),

The Rose Satin Drawing Room, Carlton House (looking North) c. 1817,

pPencil, watercolour, bodycolour and gum arabic, from Henry Pyne, History of the Royal Residences. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 922180. (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2021.

This exhibition is the product of a one-month residency at the Georgian Papers Programme, funded generously by WRoCAH, looking at the series GEO/ADD/19 Georgian Inventories, available in digitized form as part of the Georgian Papers Online. The description ‘inventory’ only goes some way to capturing the rich array of documents that we find in this collection, which consists of 103 items, varying from a few pages in length to a few thousand, and spanning the reigns of King George I (1704-1720) through to King William IV (1830-1837).

When we think of inventories, what typically comes to mind are probate inventories — that is, lists of moveable goods belonging to an individual recorded after their death as part of the process of obtaining probate.[1] While several of the records here were drawn up after the death of a monarch, the bulk of the documents may be better understood as catalogues that group together specific types of objects for the purposes of record-keeping and monetary valuation. There are a few intriguing outliers, such as a GEO/ADD/19/1, a description of the painted ceiling in the Queen’s state dressing room at Windsor Castle; GEO/ADD/19/16, the letter-book of George Villiers, bailiff to George III; and GEO/ADD/19/17, printed copies of several dukes of Buckingham’s wills. The majority, however, are concerned with documenting furniture, art, plate and dining services, busts, arms and armoury, and clocks, and their movement between the different royal palaces. The inventories provide details such as descriptions of the objects, where the objects were purchased or from whom they were commissioned, the date of their acquisition, and their location, measurements and weights. They can therefore tell us a lot about the material culture of the royal palaces, and the ways in which these spaces changed through time.

Sir William Beechey (1753-1839), George IV when Prince of Wales (1803), oil on canvas. Royal Collection Trust

RCIN 400511. (c) Her Majesty the Queen 2021

It is important to recognize that the inventories were rarely static representations of objects at a given moment, but instead acted as working documents, annotated throughout subsequent reigns in order to keep track of items in the royal collections. We find such annotations continuing to be added as late as the early 20th century, when Queen Mary (1867-1953) utilised the inventories as part of a larger project to reacquire items which had been dispersed from the royal collection. The inventories therefore occupy a strange place within the royal collections, being both documentary evidence of the objects in the collection past and present, and archival records in their own right. The inventories consequently have been heavily employed to inform our understanding of the art, architecture, and ambitions of the Georgian monarchy, but rarely looked at as an object of study in themselves.

The focus in this virtual exhibition will be primarily on the inventories of George IV (1762-1830) as Prince of Wales, Prince Regent, and King, which constitute more than half of the inventories in the collection. Section 2 walks us through the various inventories taken at Carlton House, George’s lustrously fitted-out London residence, first acquired when he came of age in 1783 and later condemned and demolished in 1827. The following sections of the exhibition then hone in on less-explored features of the inventories, as well as providing advice along the way to anyone interested in beginning their own investigations into the Georgian Inventories. Section 3 looks at the place of George’s private propert in the inventories, and the exhibition concludes with a discussion of the person who took the inventories.

_______

[1] See Giorgio Riello, ”’Things Seen and Unseen”: The Material Culture of Early Modern Inventories and their Representation of Domestic Interiors’, in Paula Findlen (ed.), Early Modern Things: Objects & their Histories, 1500-1800 (Abingdon, 2013), p. 137.