Medicine and the Georgian Navy

Ayesha Hussain and Anna Maerker, Department of History, King’s College London

The long sea voyages of the Georgian period took their toll on the health of sailors. Most dreaded of all was scurvy, a disease caused by Vitamin C deficiency. On a naval voyage to the South Seas under Captain George Anson in the 1740s, navy chaplain Richard Walter witnessed the crew’s suffering: “putrid gums, ulcers of the worst kind, rotten bones, and a luxuriancy of funguous flesh”, and, for many, death.

Fig 1: Leg of a patient with scorbutus (scurvy), 1887. By: Godart, Thomas . Courtesy of St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives & Museum, Wellcome Images.

Not surprisingly, then, the prevention of disease on board became a key concern to British officers and medics. Upon the return of George Anson, who had lost three quarters of his men to scurvy, Scottish naval surgeon James Lind (1716-1794) began to experiment systematically with different foods to determine whether they were effective in preventing the outbreak of scurvy (Fig.1). While the concept of vitamins was still unknown at the time, Lind documented that citrus fruits, in particular, and other foods with a high vitamin C content, improved the condition of patients. In 1795 the British Royal Navy ordered the routine use of citrus juices on their ships. Following this, the incidence of scurvy decreased markedly, as citrus fruits were widely accepted to be antiscorbutics.

Fig 2:James Lind Encyclopaedia Britannica By I. Wright, after a portrait by Sir George Chalmers, 1783

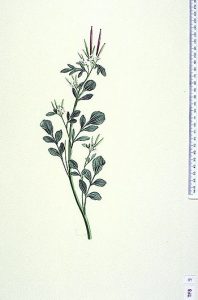

On his Tahitian voyages in the 1770s, Captain James Cook (1728-1779) used a wide range of foods to prevent or combat scurvy – from malt and citrus fruit to mustard and sauerkraut. Cook’s crew also harvested plant species for food from South America, Tierra del Fuego, South Pacific Islands, Tongo, New Zealand, Australia, Great Britain, The Falkland Islands, and Kerguellen Island. Thus they discovered scurvy-preventing plants such as Cardamine glacialis, found in South America, which became known as ‘scurvy grass’ (Fig.2). As Cook’s crew were rarely at Sea for more than 60 days, and were encouraged by their captain to eat green salads and plants, outbreaks of the dreaded disease were rare on his ships.

Fig 3: Cardamine Glacialis Discovered in Terra Del Fuego Jan 1769 Artist: Jabez Goldar Natural History Museum Collection: TF.0008./.0003

As the causes of many diseases were still unknown, naval medics investigated a range of potential causes beyond malnutrition. The cramped living conditions on board ship came under special scrutiny, as a prevailing medical theory taught that infections were transmitted by foul air. In order to prevent disease and the transmission of infection, it seemed of great importance that ships should smell sweet. It became routine that the ships’ decks would be cleansed regularly. This also led to the widespread use of ventilation below decks. As there was little fresh water to spare, the men placed their efforts into washing their clothes regularly, instead of themselves, considering there was also no suitable place to bathe. Captains were liable to be blamed for keeping dirty ships if disease broke out on board, so officers had good reasons for attending to the cleanliness of their ships and their crew.

Sources and further reading

Richard Walter, A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1740, 1, 2, 3, 4, by George Anson (1748).

James Lind, A Treatise of the Scurvy in Three Parts (1753).

James Cook, The Journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery. I. The voyage of the Endeavour, 1768-1771 (1893).

Philip Edwards (ed.), The Journals of Captain Cook (1999).

N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (1986).

[…] Georgian Papers Programme: Medicine and the Georgian Navy […]