Fading in to the Archives: Queen Charlotte’s (Missing) Papers

By Rachael Krier, Metadata Creator at the Royal Archives

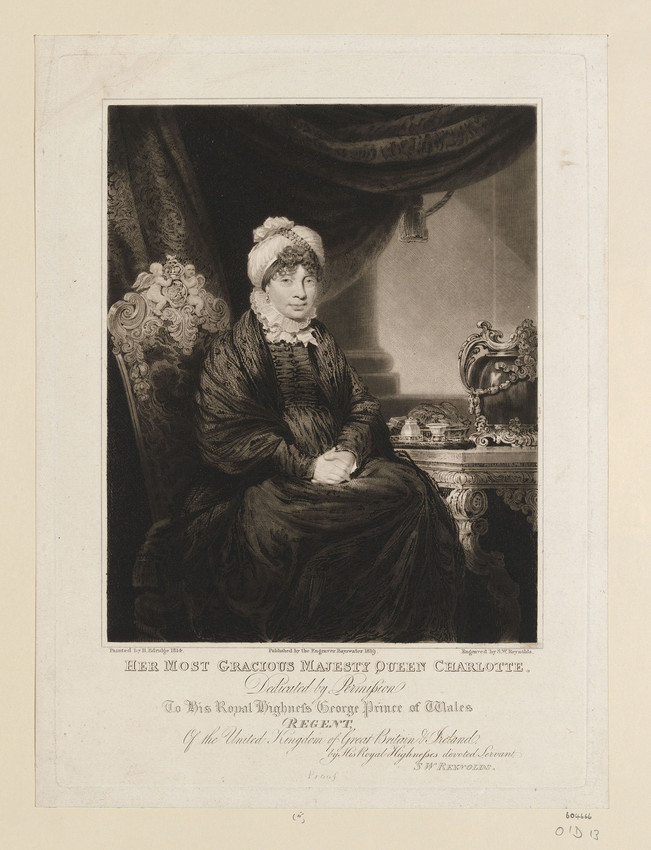

Who was Queen Charlotte? Wife of George III and mother to George IV (and many others) is only part of the answer. As with many queens in history, Queen Charlotte is often overshadowed by the larger personalities of her husband George III and her favourite son, George IV, and she remains something of an elusive figure. Part of the reason for such elusiveness lies within her surviving papers – or lack thereof. Although there is a collection of Queen Charlotte’s papers published on Georgian Papers Online, it is important to note that these could not really be said to be the queen’s own archive as it contains letters from her rather than to her.

Queen Charlotte’s will (a copy of which is GEO/MAIN/37057) contains no specific provision regarding the fate of Queen Charlotte’s papers. Instead this responsibility falls to Sir Herbert Taylor, one of the executors, former Private Secretary to George III and also to his Queen Consort. Among the probate papers preserved at the Royal Archives is a document relating to the valuation of her estate (ref GEO/MAIN/36821-36825) which is to be divided between her younger daughters: the Princesses Augusta, Mary, Elizabeth, and Sophia. From this we can determine the immediate fate of Queen Charlotte’s papers:

‘The Executors have been engaged with the Assistance of Mrs & Miss Beckedorff in examining & clearing Her Majesty’s Presses, Bureaux &c of all Letters, and Papers; of all Trinkets, Articles of Jewellery and other Effects; – of the Papers, all that were immaterial have been destroyed including /with Their Royal Highness’s Permission/ the Letters from The Princesses, excepting those from the Hereditary Princess of Hombourg, which are reserved for Her Royal Highness’s Pleasure. Those from The Prince Regent, collected and put by for Delivery to His Royal Highness. Her Majesty’s Correspondence and Papers, which appeared material, have been selected and reserved for further Consideration & Disposal, and will be arranged and classed as soon as possible.’

It is important to note that even at this stage only documents that ‘appeared material’ have been retained; the preservation criteria are not known. The princess referred to above who retained possession of her sister Elizabeth’s letters – or at least saved them from immediate destruction – is probably Princess Augusta who appears to have written to Sir Herbert with further instructions concerning the queen’s papers. This letter is not known to still exist but we can ascertain its substance from a memorandum by Sir Herbert to the princesses dated 13 February 1820 (ref VIC/ADDR/44). Here he records that, as per their commands, he has destroyed:

‘All the Letters from the late King [George III] to the Queen

All those from the Dukes of Clarence & Sussex

All those from the late King to the late Princess Amelia and those from Her Royal H to the late Queen

All the private Letters concerning the late Princess Charlotte, excepting those in which the present Queen [Caroline] was a Party concerned

All other Letters not relating to Official Transactions’

These records were probably destroyed precisely to frustrate historians as well as contemporaries should these papers fall into the ‘wrong’ i.e. unsympathetic hands. Ultimately, the Georgian Papers are private family archives (albeit of one of the most famous families in the world) and there is therefore no motivation for family members to keep documents that may prove to be painful or embarrassing to themselves – but there is every motive to destroy them. Destruction rather than preservation may be the best means of ensuring that image and legacy are kept intact; social norms and attitudes do change over time but not necessarily in a progressive linear fashion. The exact motivations and fears of the princesses in ordering the destruction of these papers is again not known but it does not necessarily mean that the family had something to hide.

In the above memorandum, Sir Herbert also notes:

‘NB The Letters from the Princesses had been previously destroyed and those from the present King [George IV] returned to Him’

It is very likely that the letters from the prince to his mother referred to here are those within the boxes of George IV private papers (uncatalogued at the time of writing) while the queen’s letters to her eldest son form the backbone of papers in Queen Charlotte’s collection. Once these collections are fully catalogued, it will be interesting to determine the overlap between them but in the meantime some of their letters and replies can be found in transcript in editions of Arthur Aspinall’s Correspondence.

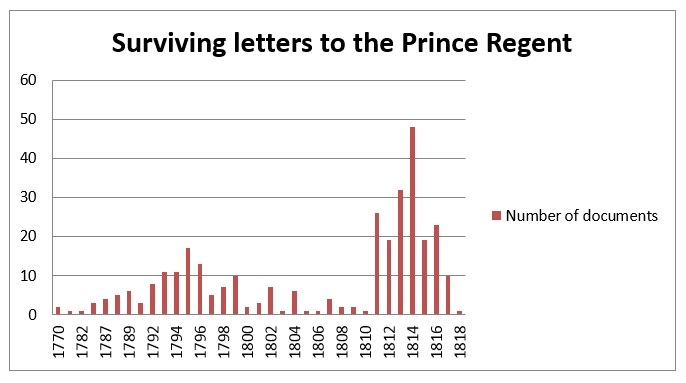

Of the 3 volumes and 406 documents within the Queen Charlotte collection (QCH), 313 are letters to George IV as Prince of Wales and later as Prince Regent. These letters cover the period from 1770 until the queen’s death in 1818 although not evenly as the chart below suggests:

Given the patchy nature for some of the years, it seems likely that the letters were weeded although who would have undertaken this – whether it was Sir Herbert before his death in 1836 or one of George IV’s executors or even more recently – is less clear.

It would be unfair to paint Sir Herbert as the destroyer of archives. In the aforementioned memorandum, he makes clear that the documents retained included ‘Official Correspondence in 1788-9 respecting the King’s Illness’ which contains ‘very few Papers’, also those for the illness in 1804 of which there are again few, and for the illness in 1810-1811 noted as ‘rather voluminous’. The ‘Official Correspondence’ here presumably refers to the Queen Charlotte’s own official papers as queen rather than those of her husband. Looking at the basic box lists for the uncatalogued George III Calendar during these years there is nothing to suggest any correspondence within these papers on the matter of the king’s health with the queen (in whom responsibility for the king’s person was vested during his illnesses although oversight of the day-to-day management was undertaken by the Queen’s Council and after her death, the Duke of York’s Council). Queen Charlotte’s own Calendar appears to have been destroyed; her only official papers within the Georgian Papers are copy letter books (ref GEO/ADD/41) of letters and correspondence with other heads of state offering the standard congratulations and commiserations on the births, marriages, and deaths of foreign royalty along with letters of credence for foreign officials. These volumes were originally part of the library of Sir Thomas Phillipps and were only purchased for the Royal Archives in 1967 but the precise nature of their creation – why they were even copied in the first place, when, and by whom – remains unclear.

Sir Herbert also goes on to list further documents retained as:

‘The Correspondence respecting the Windsor Establishment and other Public Arrangements at the period 1811 [?ref GEO/MAIN/50260-50350]

The Correspondence between the Queen and Her late Majesty’s Council

- Correspondence with the present Queen [Caroline] and all the Papers connected with it

- Correspondence respecting Mr Villiers with Lord Clarendon &c &c [?ref GEO/MAIN/36627-36628, 36630-36640]

- Correspondence & Documents respecting Mr Bolton’s Claims [?ref VIC/ADDR/37a-39]

- Correspondence with & respecting Sir Lucas’s Pepys’ Claims

- The Correspondence respecting the Duchess of Cumberland

a few odd Letters from M Genl Taylor an Trustee and other Business’

Of the latter numbered documents, Sir Herbert writes: ‘it would by no means be adviseable to destroy, in as much as a Reference to them may become necessary, in Justice to the late Queen’s Proceedings, and if Their Royal Highnesses agree in this Opinion, they should be deposited when, under Their Sanction, access can be had to Them at any future Period, and therefore not with the late King’s Papers.’ Excepting the references noted in square brackets, none of the above papers are believed to exist although it is possible that the ‘few odd Letters from [Major-General] Taylor’ are those in GEO/MAIN/50260-50831 (as yet uncatalogued) and detailed cataloguing of the Georgian Papers as a whole may reveal more on the claims of Sir Lucas Pepys and on the Duchess of Cumberland.

Understanding the archive is key to understanding a person and their legacy. While it is impossible to estimate the quantity of papers that were destroyed or their likely contents, the gaps and silences within the archive can at least be understood even if we will never fully understand Queen Charlotte and her role within her family, court, or society.