Was George III Really A Tyrant?

By Marie Pellissier, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

Was George III really a tyrant? The answer to that question certainly depends on who you ask. The writers of the Declaration of Independence, who included a list of twenty-seven reasons why the king was a despot in order to justify their separation from Great Britain, would presumably think so.

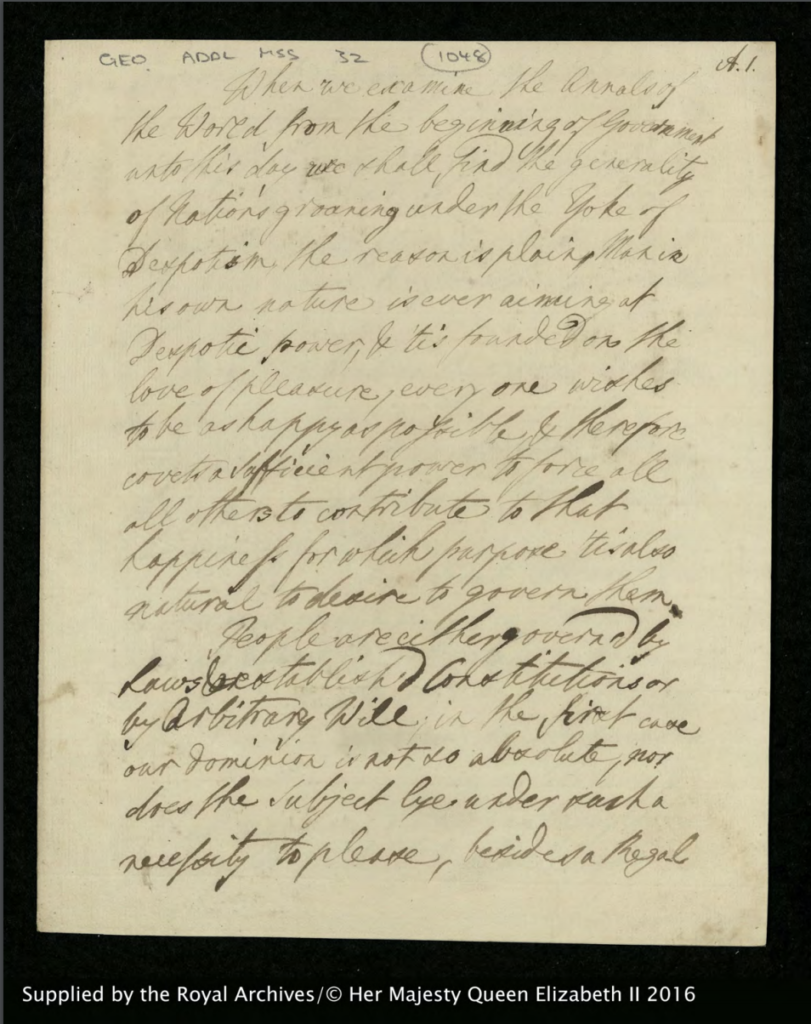

George III himself, however, would probably disagree. And, to back himself up, he might point you to an essay he wrote sometime in the late 1750s or early 1760s (GEO/ADD/32/1055-7). George III wrote a large number of essays, few of which were dated, on topics from history and geography to mathematics, moral philosophy, and government (for a deeper dive into the essays of George III, visit our virtual exhibit “The Essays of George III: An Enlightened Monarch?” by Jenny Buckley).

Click on the image to see the essay in full. For a transcription, click here.

At the time he wrote this essay, George III was in his late teens or early twenties. His father, Frederick, Prince of Wales, had died in 1751, making George the heir to his grandfather, George III. As Karin Wulf and Arthur Burns wrote, George III may have written this document under the tutelage of Lord Bute, his first prime minister. In the late 1750s or early 1760s, he would have been getting ready to rule in his own right, and determining how his reign would be different from that of previous Hanoverian monarchs. (This document was featured in our virtual exhibit “An Audience for Hamilton’s George III, Michael Jibson, with George III Himself: A Virtual Exhibition,” by Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf).

In this essay, George III examined the difference between a despotic monarch and a constitutional government. A society (in the young royal’s mind, this could only be a monarchy) governed by laws and “establish’d Constitutions” put great demands on its ruler. A ruler must have a thorough understanding of his people, which “cannot be acquire’d without great labour & Study, but that is the bane of pleasure, & revolts the natural idleness that attends us.” In other words, a constitutional monarchy required more work from the monarch because the people were not absolutely bound to the monarch’s will.

In contrast, a despotic monarch paid no attention to his people, reducing them instead to state of “servile compliance” to the ruler’s will. Tyranny can only be imposed, George III wrote, by “violence & an arm’d force,” but this creates a significant risk for the sovereign. The military, realizing that they are essential to the “safety & power” of the monarch, may take advantage of the situation and exercise too much influence over the sovereign.

The first part of the essay focuses on the harmful effects of tyranny on the tyrant himself. Kings should be careful not to listen to advice that might encourage them to “use Arbitrary power” for the sake of preserving their power. The ideal monarch must resist the temptation to take the easy path of tyranny and instead put in the work to heed the concerns of their subjects. This is “the method to reign in Peace & Prosperity, [and] to transmit the Scepter to their posterity,” an essential concern for any self-respecting monarch.

But what about the people subject to such a tyrannical sovereign? They are kept in woeful ignorance, George III writes, of a “proper idea of Justice… & also the reciprocal engagements that united the Members of a Society.” Why? Because “to acquire this knowledge there must be thought, but who dares think under an Arbitrary Government”? Who dares, indeed. Tyrannical governments stifle the voices of citizens who might offer enlightened advice to their sovereign. Such a government also “deprives them of all courage to resist an Enemy” because of their addiction to “Luxury, Idleness, & Effeminacy” and disinclination towards discomfort.

George III’s coronation portrait by Allan Ramsay, 1762.

This essay, written either right before or very soon after George III ascended to the British throne, shows us a royal who is superbly aware of his role as a monarch in a constitutional system. It also reminds us that the subjects he envisioned were all male, men being the only ones who, in Enlightenment understandings, enter into the social contract which bound society together (and even then, not all men!). By enumerating the ways a monarchy can go wrong, George III might have been writing a series of reminders to himself, and could have called this essay (in today’s words) “How Not to Mess Up Being King.”

The Americans assembled in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776 would probably have rolled their eyes at young George III’s youthful assertion of his good intentions, as Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf have suggested. In the Declaration of Independence’s list of twenty-seven grievances against the King, six accuse the king of abusing military power in the colonies. “He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.” This, the colonists believed, was a clear example of despotic behavior. Many of the other grievances accuse George III of disrespecting the people’s traditional right to self-representation. The colonists point to their “repeated Petitions” as evidence that they had tried to reach an understanding with their monarch. Instead of putting in the “labour & Study” to hear and understand his people, the Americans seem to say, George III had taken the easy road of tyranny, refusing to rein in Parliament or act on behalf of his aggrieved colonial citizens.

And yet, George III’s essay is very clear: the consequence of tyranny is a mute citizenry, who don’t dare to think or speak against the government. The British tradition of free speech and the proliferation of political print culture in the eighteenth century points to a citizenry who felt free to speak and print their opinions, and even the Declaration of Independence itself is the product of citizens free to think, discuss, and name their grievances.

So… was George III a tyrant? Depends on who you ask.

References

GEO/ADD/32/1055-7 (George III on Despotism)

Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf, “An Audience for Hamilton’s George III, Michael Jibson, with George III Himself: A Virtual Exhibition,” virtual exhibit, 2018. https://georgianpapersprogramme.com/an-audience-for-hamiltons-george-iii-michael-jibson-with-george-iii-himself-a-virtual-exhibition/

Jenny Buckley, “The Essays of George III: An Enlightened Monarch?,” virtual exhibit, 2019. https://georgianpapersprogramme.com/the-essays-of-george-iii-an-enlightened-monarch-a-virtual-exhibition-by-jenny-buckley/

National Archives and Records Administration, “The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” 2018. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript