The Madness of George III revisited: reflections on Mental Health in the Georgian World

By Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf

Arthur Burns academic director, Georgian Papers Programme, and professor of Modern British History at King’s College London

Karin Wulf academic director, Georgian Papers Programme and executive director of the Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture and professor of history at William & Mary, USA

___

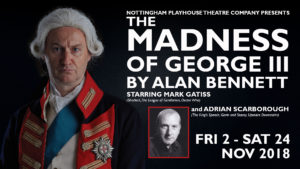

Despite his long and storied reign, that King George III suffered bouts of mental illness is among the handful of things most people know about the monarch. One of the key aims of the Georgian Papers Programme is to tackle even seemingly well-worn subjects from fresh angles. Thus, with the medical papers of George III recently made public through the GPP, heightened public attention thanks to the production of The Madness of George III at the Nottingham Playhouse last year, and both medical history and contemporary attention offering new perspectives on mental illness, the theme of the king’s madness seemed an obvious choice for a focal point as we mark five years of the GPP.

On 5 November 2019 we were delighted to host an event at King’s College London entitled Mental Health in the Georgian World. We produced an online exhibit in advance of the event, highlighting some of the topics we would raise and the materials from the Royal Archives, as well as images from the Royal Collection Trust and elsewhere, that illustrate the periods of the king’s illness. The event attracted a great deal of interest, with applications to attend far exceeding the capacity of the hall, so we are very pleased to be able to say that it is now possible to watch a permanent record of the proceedings on GeorgianPapers.com, reproduced at the end of this blog.

Adam Penford, Barbara Taylor, Mark Gatiss and Mike Brown in conversation on 5 November

In this blog, we want to offer a few reflections on a very memorable occasion, and also to suggest why this subject is an example of the potential of the GPP to illuminate critical historical subjects for our own time. The idea of the event originated in three things. First, the Georgian Papers Programme wanted to celebrate progress since its initiation some five years ago, and also the renewal of agreements among the partners in the project (the Royal Collection Trust, King’s College London, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, and William & Mary) which will underpin its activities between now and 2024.

To do this, we wanted an event that would somehow encapsulate some of the distinctive features of this ambitious project: its openness to interdisciplinarity and collaboration in its widest sense; its aim of underlining the particular relevance of the history of the Georgian period to our own times; and the dividends that result from the integration of different aspects of academic and archival work which more customarily take place in sequence, but which in the Georgian papers programme are occurring simultaneously, from cataloguing and conserving the archive through scholarly research to teaching and public dissemination. With the extraordinary medical papers of George III now digitized, and an enduring subject of scholarly and public interest, the theme of George’s mental illness seemed an obvious choice for our evening.

Secondly, those medical papers of George III are a striking example of the richness of the archive which the Programme is making public. Many of the papers have not previously been available to scholars, the normal restrictions of access over the years inevitably associated with the location of the papers in the Round Tower of a functioning royal residence and in the private archive of the sovereign rather than a public repository in this case being reinforced by understandable sensitivity around the personal medical history of a monarch suffering from a condition, mental illness, which has traditionally been stigmatized in ways not associated with other illnesses.

Moreover, in recent years, some members of the Royal Family have played an important and public role in trying to reduce this stigma and encourage more open discussion of issues around mental health In this context we are struck by the extraordinary richness of this archive, containing not only remarkable documents such as Robert Greville’s first-hand memoir of his engagement with the sufferings of his king as his personal equerry (long available in print) but also the daily reports of the physicians attending the monarch not just in the famous incidence of illness in 1788-9 which provoked the so-called ‘Regency crisis’, but in the long and bleak period of the king’s last decade during which his mental condition conspired with the effects of blindness and deafness and the onset of extreme old-age. Publishing it online makes more readily available for integration into discussion perhaps the single best-documented case history of its time.

Thirdly, the Georgian Papers Programme had developed an ongoing engagement with the key source of public awareness not merely of George’s illness, but of George more generally: Alan Bennett’s 1991 play the Madness of George III¸ later filmed to great acclaim as The Madness of King George. In 2017 we had staged a conversation between Alan Bennett himself and the director of both the first production at London’s National Theatre and the film, Nicholas Hytner chaired by King’s professor of theatre Alan Read, which can still be viewed; then in 2018 we had the opportunity to work with Nottingham Playhouse and NTLive on their outstanding production of the play which played to sell-out audiences in Nottingham and packed venues across the world for the live relay. We provided programme notes and a briefing for the cast, images of key documents for the prop department and a pre-show talk in Nottingham – and then took the actor playing George III, Mark Gatiss, on a visit to Windsor to see key manuscripts in the collection associated with the king’s illness, the visit being filmed to form part of the pre-show introduction broadcast by NTLIve, The World Turned Upside Down, and providing the basis of a much-viewed online exhibition on GeorgianPapers.com, The Madness of George III Explored.

Thirdly, the Georgian Papers Programme had developed an ongoing engagement with the key source of public awareness not merely of George’s illness, but of George more generally: Alan Bennett’s 1991 play the Madness of George III¸ later filmed to great acclaim as The Madness of King George. In 2017 we had staged a conversation between Alan Bennett himself and the director of both the first production at London’s National Theatre and the film, Nicholas Hytner chaired by King’s professor of theatre Alan Read, which can still be viewed; then in 2018 we had the opportunity to work with Nottingham Playhouse and NTLive on their outstanding production of the play which played to sell-out audiences in Nottingham and packed venues across the world for the live relay. We provided programme notes and a briefing for the cast, images of key documents for the prop department and a pre-show talk in Nottingham – and then took the actor playing George III, Mark Gatiss, on a visit to Windsor to see key manuscripts in the collection associated with the king’s illness, the visit being filmed to form part of the pre-show introduction broadcast by NTLIve, The World Turned Upside Down, and providing the basis of a much-viewed online exhibition on GeorgianPapers.com, The Madness of George III Explored.

Mark Gatiss with Arthur Burns and Oliver Walton, GPP Programme Coordinator at the Royal Archives, during his visit to Windsor to view the exhibition we prepared for him in October 2018

We designed a panel to bring together a variety of perspectives on the king’s mental illness that would reflect the insights we had already gained from these activities. For obvious reasons, we wanted an informed historical perspective, and so we invited two professional historians with complementary expertise: Mike Brown, who has written extensively about the medical profession in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and provincial ‘mad doctors’ in particular; and Barbara Taylor, a leading authority on the self and feminism in the eighteenth century, co-convenor of the seminar on Psychoanalysis and History at the Institute of Historical Research and author of a remarkable personal history of mental health care in twentieth-century Britain, The Last Asylum. For a professional medical perspective, we called on Sir Simon Wessely, professor of Psychological Medicine at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London and chair of the recent government review of the Mental Health Act, who had worked with us in advising the Nottingham production, and who also has a particular interest in the historical specificity of the experience of mental illness. We knew from our work with the Nottingham team that the experience of acting in and directing the play had led both Mark Gatiss and the artistic director of Nottingham Playhouse, Adam Penford, to reflect on the king’s experience and that of the family and court around them, and how to embody these for a contemporary audience. And finally, as convenors, we brought our own knowledge of the Georgian Papers archive, and questions as historians of the period as well as professionals employed in higher education, where issues around the wellbeing of both students and staff are achieving a new prominence.

So, what did we learn from the conversation that resulted?

First, that it pays to choose your panellists carefully! We were enormously grateful for all those who took part for their willingness to engage with each other and take part in precisely the kind of exchange of ideas and perspectives that we had hoped for. We hope that anyone watching the discussion will agree that the variety of perspectives helped us all achieve an enriched understanding of our own takes on the subject, regardless of our starting points.

From our particular perspective as academic historians, we came away excited and encouraged to pursue a series of different enquiries, some stimulated by the process of preparing for our role of convenors, and others crystallised by the themes that emerged in the discussion, but all of them shaped in meaningful ways by the encounter. In the UK in particular, there is currently great emphasis on the beneficial “impact” that academic research can have on non-academic activity. But in the encounter between research and other forms of cultural production, the “impact” can be equally significant the other way, especially if the encounter takes place early enough in the research process. And that was certainly the case here.

First, as we prepared for the event by looking at what had been written on the ‘madness’ of George III from shortly after his death in 1820 up until the autumn of 2019, when the latest academic paper on the topic appeared, we were struck by the fascinating interplay of the interpretations of historians, the retrospective diagnoses of medical authorities and wider public understandings and representations of the ‘mad king’ over almost two hundred years. Parts of that story have been told before, but rarely from an interdisciplinary perspective. This underscores the complementary importance of the historical work of the physicians, and the contributions of historical writers and sources to shaping doctor’s interpretations. Just how rich that dialogue has been, and the undercurrents on both the historical and medical sides emerged strongly in the conversation on November 5th, not least in contributions from Simon Wessely and Mike Brown, and we aim to explore the historiography further, building on the bibliography we have already mounted as part of the associated online exhibition.

Sir Simon Wessely in conversation on 5 November

Secondly, in our reading we were struck both by the neglect of the experiences and responses of the women in George’s immediate family and at court in many approaches to and depictions of the king’s illness, despite a wealth of material in the archive with which we were familiar. At the same time, we were shocked at some of the ways earlier writers have adduced George’s familial relations as an explanatory factor in his illness. Here insights from Barbara Taylor as a historian with a particular interest in gendered experience and from the director and actor in a production which was required to enact representations of those experiences encouraged us in our hunch that there was a neglected and sometimes violent dimension to the story of George’s Illness that we should seek to illuminate.

Barbara Taylor and Mark Gatiss in conversation on 5 November

Finally, our own reading of the documents produced by the king’s doctors, and Mark Gatiss’s comments on the experience of embodying and ‘performing’ the king in particular, alerted us to an under-examined aspect of the king’s illness – the extent to which his behaviour and treatment could be used to illuminate the monarch’s self-conscious performance of his sovereign role. The ‘disinhibiting’ aspect of mental illness combined with the strict protocols associated with royalty might let us explore George’s own sense of his identity even at moments, in his periods of illness, when it was most vulnerable.

We hope to be able to produce some initial reflections on these themes in the not too distant future, including at the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies conference in January. Meanwhile we again thank all those who contributed to the success of this evening, and encourage those who missed the event to take advantage of both the online exhibit and the recording to join in this re-evaluation of the madness of George III.

MENTAL HEALTH IN THE GEORGIAN WORLD: FULL RECORDING.

With thanks to Nottingham Playhouse, NTLive!, the Royal Collection Trust, the speakers, King’s College London, especially the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, the Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture and William & Mary for support in making the event on November 5 possible.

Extract from the NTLive! broadcast of the Nottingham Playhouse production of Alan Bennett’s The Madness of George III in the recording are by kind permission of NTLive and Nottingham Playhouse. This extract from ‘The Madness of King George III’ by Alan Bennett (© Forelake Ltd) is used by permission of United Agents (www.unitedagents.co.uk) on behalf of Forelake Ltd.

[…] Mental Health in the Georgian World: The ‘Madness’ of George III: recording of symposium with Mark Gatiss, Adam Penford, Mike Brown, Barbara Taylor, Karin Wulf and Arthur Burns, 5 Nov. 2019. An associated blog post by Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf at The Madness of George III revisited: reflections on Mental Health in the Georgian World. […]