Toymakers to the King: Play, Toymen, and Childhood in the Early 19th Century

By Sarah Donovan, Omohundro Institute Apprentice, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

A toy house, a doll, a tambourine, and a toy drummer. These are just a few of the toys George IV ordered as Prince of Wales from James Gregory in 1801.[1] These toys were not the only ones the Prince of Wales ordered, nor was James Gregory the only toymaker enlisted by the royal family. Between 1800 and 1830, George IV made fourteen different purchases of toys from five different toymakers. What kinds of toys did royals play with? And what can these toys tell us about childhood in the early 19th century?

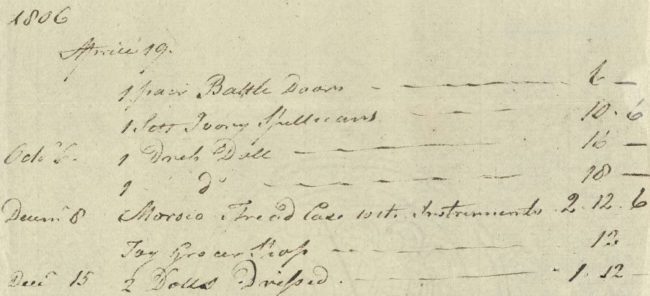

1806 bill

GEOMAIN29117

John Newbery, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book cited in Brown, “Capturing (and Captivating) Childhood,” 426.

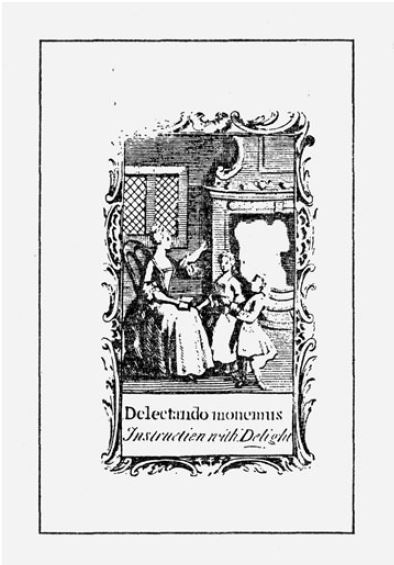

During the 18th and 19th centuries, toys served as an extension of a child’s education. Enlightenment thinkers, such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argued children’s education should derive from experience and interactions with their environment.[2] Locke and Rousseau’s arguments for an interactive education is evident in the increasing number of illustrated children’s books throughout the 18th century. Authors reasoned that illustrations and visual aids would better facilitate this experiential learning.[3] While books were already in the domain of children’s education, this interactive approach placed toys in a unique position, as these objects straddled the line between education and play.

Mrs. Dudley, 1832

RCIN 72341

Many of the bills charged to George IV contained toys, such as dolls and toy soldiers, that sent specific messages to children about social and gendered expectations. In giving girls dolls, doll houses, and toy kitchens to play with, parents and caretakers signaled to young girls the virtues of female domesticity.[4] On the other hand, giving boys a “Box of Soldiers” to play with reinforced the notions of masculinity that would come to define boys’ character as they grew.[5] These gendered toys became part of a child’s education, as they were able to “experience” society through play. The various bills from toymakers preserved in the Georgian Papers, illustrate the wide range of toys that George IV purchased; however, these bills of purchase also demonstrate the emerging importance of toys.

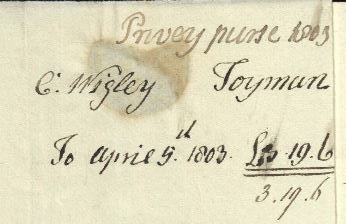

GEO/MAIN/29104-29104a

While the frequency at which George IV purchased toys is interesting, the men he purchased these objects from are particularly noteworthy. The first bill for the purchase of toys to appear in the Privy Purse Accounts of George IV was an 1801 purchase from James Gregory. On the outside of the bill, Gregory’s occupation is classified as a perfumer, not as a toymaker.[6] However, by 1803, George IV employed Charles Wigley, a recognized “Toyman,” in the production of royal toys.[7] Unlike Gregory, Wigley and the three other toymakers employed by the royal household (Alder & Son, R. Ordway, and Charles Wayte) all explicitly held the distinction of “Toymaker.” Wigley’s specific title as “Toyman” further speaks to the importance of toys in the 19th century. As toys became tools of education, their production became more important as well. By spending the time and money to order toys, George IV demonstrated his commitment to the importance of toys and play for a well-rounded education.

[2] Ranjana Saha, “Children in the Mind: Paginated Childhoods and Pedagogies of Play,” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 48 (November 2011): 54.

[3] Penny Brown, “Capturing (and Captivating) Childhood: The Role of Illustrations in Eighteenth-Century Children’s Books in Britain and France,” Journal for Eighteenth Century Studies 31, no. 3 (2008): 425.

[4] GEO/MAIN/29104-29104a, GEO/MAIN/29100-29100a