Dancing with the (Georgian) Royal Family

By Hillary Burlock (GPP BSECS fellow and doctoral student at Queen Mary University of London)

When I first went to the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, I was on the hunt for references to Philip Denoyer, dancing master to George III’s family. While I was able to find some information in the accounts of George III and George IV as Prince of Wales, I also came across anecdotes surrounding dance education and dancing at balls in the correspondence of George III’s children, illuminating the personalities of the late eighteenth-century royal family. From the correspondence of the royal children, one can glean insight into how their relationships with their parents and siblings developed.

The children of George III were instructed in dance by French dancing master Philip Denoyer. He was the son of George Denoyer, who had been dancing master to Frederick, Prince of Wales during the reign of George II, coming from a line of dancing masters who instructed at the royal court. As a young man in 1768, after his father’s retirement, Philip Denoyer was listed as dancing master to the new Prince of Wales, when the heir apparent was 6 years old.1 From 1777 to his death in 1788, Denoyer was paid an allowance of £150 in Queen Charlotte’s household, in addition to £23 15s. in the Prince of Wales’ and Duke of York’s accounts. 2 When learning to dance, the princes and princesses would have learned to walk genteelly, to bow and curtsey, the proper carriage and deportment of the body, and different dance forms with their figures and footwork. Under Denoyer’s tuition, the Prince of Wales became an accomplished dancer, as newspapers repeatedly reported on the dancing prowess of the heir apparent. Indeed, in 1787 the Derby Mercury proclaimed that the Prince of Wales ‘was ever considered the Life of the Dance’, while the Hereford Journal praised the heir for performing minuets ‘with unrivalled elegance’ in 1791.3

Dance was a significant accomplishment in the Georgian period, as it had the ability to communicate and engage with other people. It was a skill that few could do without, and that included the royal family. While the Prince of Wales was an accomplished dancer, his sister the Princess Royal did not have the same ear for music and skill for dancing.4 Indeed, the Princess Royal wrote to her younger brother, Prince Augustus, in August 1788 that ‘I am afraid that you will not have a very great opinion of me from this confession as in general a love of Music to distraction runs through our Family of which I alone am deprived[,] pray my dear Augustus do not love me less for my want of Ear and consider that Music is about the only thing that we differ about’.5 Musicality pertained to having musical talent, to having a sensitive ear to listen for, and coordinate with, correct pitch, rhythm, beat, and timing. In the minuet, it was apparent when steps, rhythms, and timings were uncoordinated and unsynchronised with the music and one’s partner. The lack of musical aptitude, which was viewed as essential for an accomplished dancer, was of significant concern for the Princess Royal in the summer of 1780, keeping up with her dancing lessons. She wrote to Mary Hamilton, courtier and governess to the princesses, that ‘I have behaved well in every occasion except last Wednesday, that I danced ill… However, I hope that you will not give me quite up, since I have done everything else well, and that I dance [sic] better last Friday.’6 Despite constant practice, the lack of natural skill for music and dancing led to her embarrassment at royal birthday balls.

Princess Elizabeth, George III’s third daughter, conversely, loved to dance and caper about the royal residences. She wrote to her brother Prince Augustus in 1787 that on Frederick, Duke of York’s twenty-fourth birthday,the company had danced until six o’clock in the morning, ‘but however as every Body went away I could not probably stay by my self to dance capers alone so I also return[ed] to Bed.’7 The rest of the royal children enjoyed dancing with each other and at balls both in England and in Hanover.

George III’s younger sons were sent to Hanover to complete their education. Whilst abroad, they learned new, continental dances at Hanover’s masquerades. In February 1781, Prince Frederick wrote to his elder brother, the Princes of Wales, that ‘When I return to England I must teach You two different kind of Dances from what we have the least Idea of the Quadrilles, and the Waltzes, The first is a kind of Cotilion but with English Steps, The other is a kind of Allemand but much prettier[;] they generally introduce the Waltz into the Quadrille’.8 New dance forms were able to travel between Britain and Hanover via the princes’ correspondence and travels. Indeed, the royal brothers became a channel for cultural exchange between Britain and the continent, as the Prince of Wales sent his brother ‘a dozen pair of Accoutreman [sic] leather Soaled [sic] Dancing Pumps’ and elaborate masquerade costumes in white and pink satin and another in lilac and buff.9

Like the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York was clearly an avid dancer, who continually danced through his thin, leather-soled dancing shoes. The popular country dances that were enjoyed in England, like the Prince’s masquerade costumes, travelled across the continent to Hanover via the princes and their correspondence. In 1781, the Duke of York asked his elder brother to send books of country dance music, ‘for people are vastly fond of Our Country dances Here.’10 The royal family thus facilitated cultural exchange, helping the English country dance to spread to Europe, and cotillions, quadrilles, allemandes, and waltzes to spread to Britain’s ballrooms.

Once the royal children reached the age of seventeen (for the princes) or fifteen (for the princesses), they were expected to perform minuets and country dances at the royal birthday balls, held twice a year to mark the king and queen’s official birthdays. George III’s birthday was typically celebrated on or around 4 June. Queen Charlotte’s was celebrated around 18 or 19 January (although she had actually been born in May 1744). The day’s festivities commenced with the monarch and his family attending church in the morning, followed by a levée or drawing room at St James’s Palace in the afternoon, then a private dinner for the family, and closed with the birthday ball. The monarch’s birthday was an event where Britain’s elite, the Bon Ton, were expected to pay their respects through purchasing new garments to wear to the celebrations, attending the drawing room, and either observing or dancing minuets at the ball.

Kellom Tomlinson, The Art of Dancing Explained (London, 1735).

The minuet was a significantly stressful exhibition dance in a ball setting, let alone a court ball at St James’s Palace. It was performed by one couple at a time, in the centre of the room, with the eyes of the monarch and his courtiers on the two dancers. Following the bows and curtseys (or courtesies), the two-person dance included: the introduction; the ‘S reversed’ or ‘Z’ figure, which was repeated throughout the dance; alternated with the presentation of hands (right, left, then both). The minuet required the dancers to have great discipline and mastery over their bodies, and execute the dance with multiple layers of complexity. Not only did the dancers have to trace out the ‘Z’ pattern on the floor, but also to execute their footwork with the pas de minuet, and ornamenting the patterns with the balance, pas grave, and grace steps. The pas de minuet was executed in four steps, distributed over six beats (or two bars of music). Parisian dancing master Monsieur Malpied, of whom very little is known, explained that the four steps in the six beats took place on beats 1, 4, 5, and 6, with an assortment of stepping on the flat of the foot, raising up on one’s toes, and sinking by bending the knees.11 Learning to dance the minuet took significant time and effort, both on the part of the dancing master and his pupils, in order to perform creditably at a ball or assembly.

During the Princess Royal’s first minuet at the King’s birthday ball in 1781, the disparity between the Prince of Wales and Princess Royal’s skill was evident. The Kentish Gazette noted that ‘The Prince danced incomparably well, and very kindly took care to conceal those little mistakes which his sister committed, owing to the embarrassment of a first appearance as a dancer on so public an occasion.’12 The following year, in 1782, at the Queen’s birthday ball, she fell during a dance when the fringe of her petticoat got snagged on her shoe buckles.13 The Princess Royal, who had practised so hard to refine her minuet, was mortified by these accidents. It was important to perform creditably at the very least, but there was significant pressure for the members of the royal family and Bon Ton to perform with grace and accomplishment, because it would be reported on in the newspapers following the birthday ball. In June 1782, upon the occasion of Princess Augusta’s first minuet at the King’s birthday ball, Queen Charlotte wrote to Lady Charlotte Finch, governess to the royal family, that Princess Augusta was nervous when news of her coming out was sprung on her before the ball:

You my dear lady Charlotte know enough of Her character as to fancy to Yourself Her surprize when She was made acquainted with my intention of producing Her. She was perfectly silent for some time & grew more timorous as the moment of Our appearance approached, however She went through it very properly & I have the Satisfaction to find that Her behaviour was approved of. The News papers made Her in my opinion a truly Genteel Compliment in saying, that the World Admired the Elegance of Princess Royall, and not less the Modesty of the Royal Augusta. She really danced with all possible elegance and behaved with uncommon propriety at the Ball…14

Princess Augusta’s reaction to being informed of her first minuet performed publicly at Court indicates the significant pressure to perform well. Even the Queen paid attention to how the newspapers described her family’s accomplishments, evidently satisfied with her daughter’s creditable performance and favourable newspaper notice. The royal family was by no means above the reports in the newspapers, and were very concerned with public perception.

Figure 2: ‘View of the Ball at St James’s on the celebration of Her Majesty’s Birth Night Feby 9 1786 which was opened by their Royal Highnesses the Prince of Wales & the Princess Royal,’ 1786, © Her Majesty the Queen 2020. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 750529.

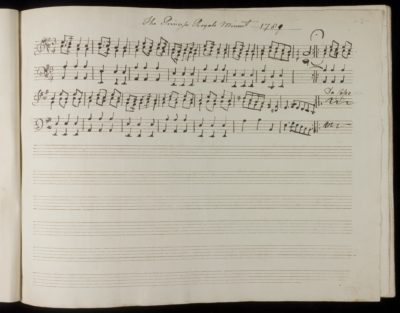

Intrinsically connected with the tradition of the royal birthday ball, in the Hanover Royal Music Archive of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, is a manuscript music book which contains sheet music written out in the hand of Princess Augusta, initialled by her on 1 December 1787. The contents of the book date between 1787 and 1789, as it also contains six transcribed ‘Minuets for Her Majesty’s Birth Day 1788 by Parsons’, six ‘Minuets for His Majesty’s Birth Day 1788’, and ‘The Princess Royal’s Minuet 1789’.15 The majority of the minuets transcribed in Princess Augusta’s music book were composed by William Parsons, affectionately referred to by the princesses as ‘Sir Billy’, Master of the King’s Musick between 1786 and 1817, and singing master to the royal family, not least the princesses, later being knighted by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the 2nd Earl Camden.16 William Parson’s minuets were even given specific recognition in January 1787 for the Queen’s birthday ball. The Derby Mercury wrote that ‘The Composition of the Minuets reflect great Honour on Mr. Parsons: – the first possessed some charming passages; – of the fifth we must also speak complimentary – it was marked with Spirit, and the Horns were introduced with a pleasing Effect.’17 Also in Princess Augusta’s music book are a few country dance tunes with accompanying figures, including ‘Mr. St Leger’s Hornpipe,’ ‘Yankey Doodle,’ ‘La Belle Gertrude,’ and ‘The Nymph’,18tunes that might have been taught by Denoyer as the royal dancing master, or danced at the royal birthday ball. Mr St Leger was certainly a regular attendee at the royal birthday balls between 1787 and 1795, according to newspaper reports containing lists of minuet dancers at court. In the year that ‘La Nymphe’ was performed at the King’s birthday ball in June 1787, so also does ‘The Nymph’ appear in Princess Augusta’s music book dating between 1787 and 1789. So, it is possible that the country dances contained in this music manuscript were written down by Princess Augusta following the birthday balls as a commemorative keepsake, preserving the music performed at these court events.

The minuets contained in Princess Augusta’s music book, when reconstructed, show a range of compositional styles, some demonstrating lightness and delicacy with others sounding much more formal. I have reconstructed these minuets on MuseScore, a music composition and notation software, which allows some of these tunes to be heard again after over two hundred years. Over the coming years, I intend to have these minuets recorded on historic instruments with the instrumentation William Parsons intended in his scores so that we can hear how the minuets would have sounded in the ballroom at St James’s Palace. The selected minuet is the Princess Royal’s Minuet from 1789, which is significant as the only minuet that we know with certainty that the Princess Royal and the Prince of Wales danced. I have provided a recording of the A and B sections. The Princess Royal’s Minuet is also significant as the opening minuet that was performed at the King’s birthday ball after his recovery from illness in 1789.

Listen to the Princess Royal’s Minuet 1789, From the Music Book, 1787-1789, OSB MSS 146, Hanover Royal Music Archive, Beinecke Rare Book and Music Library, Yale University. Transcribed, notated, and recorded in MuseScore by Hillary Burlock 2020.

Unlike the official birthday balls at St James’s Palace, the children’s birthdays were celebrated with less pomp and formality and were much more enjoyable. Many of George III’s children enjoyed dancing, and balls were hosted to mark the occasions. The Princess Royal recounted in a letter to her younger brother Augustus in 1787 that ‘my Birthday was kept and Papa gave us a very fine Ball which lasted from half past seven till six in the Morning’. All the gentlemen wore the Windsor uniform, and the ladies wore white gowns with ‘Garter Blue’ petticoats and belts.19 For Augusta’s birthday in 1791, her parents also ‘gave her a ball’ to celebrate. She wrote to her brother, Augustus, that ‘We danced 14 Country dances’, and that her eldest brother, the Prince of Wales,

Spent all Tuesday with us and chose us some of the best Tunes … but he did not dance. Papa also made us dance some Old tunes very merry ones indeed and even if they had not been pretty I should have thought them so as he chose them.20

George III preferred older, more traditional tunes than the fashionable and current tunes the heir apparent favoured. The children’s reminiscences of their birthdays reveal a family that loved to dance, bringing together the children’s friends and family. Princess Elizabeth wrote to Prince Augustus that, ‘the moment [the King and Queen] thought that a Ball would give us pleasure it was decided immediately; we shall all be in very great spirits as it brings together most of our friends’.21 The monarch and his young family enjoyed these moments when family and friends danced and laughed together, before tensions started to rise as the children became adults.

Even when the royal family travelled around Britain on royal tours, dancing was a key method of engaging and maintaining goodwill with the public. In October 1804, Mary Shirley visited Weymouth at the same time as the royal family, recounting the grand balls and fêtes held in their honour. In Weymouth’s assembly rooms, Lord John 4th Earl Poulett held a ball for the King and his family, where the royal family milled about the room, greeting all those attending before the dancing began. Upon seeing young Mary Shirley without a partner, she recounted,

The King came up to me and said, ‘Have not you got a partner?’ I curtseyed and said, ‘No, sir,’ so away he went and fetched me Lord Poulett’s second son, about twelve years old, and he made excuses to me for bringing so young a one, so I am afraid he must think me older than I am.22

George III was very attentive to Lord Poulett’s guests, eager that they should all enjoy themselves. The following week, the Shirleys were invited to a ball seven miles north of Weymouth in Dorchester, hosted by George III, where there were separate country dance sets for children and adults to join in the merriment. The entire royal family, from Princess Elizabeth to Queen Charlotte and the Duke of Cambridge tended to Mary during the evening. They secured for her Captain Jolliffe, ‘a very famous German’, and ‘an immense, large, tall officer, whose name I do not recollect’ as her partners for the five country dances that evening.23The Duke of Cambridge even helped Miss Shirley to find a good place to watch the fireworks. Mary Shirley’s brush with royalty reveals that the King loved children and dancing, as she recalled that, ‘The King stood between the sets part of the time… He was the greatest part of the time playing with the children, who made such a riot with the Duke of Cambridge. The King stood the whole evening, and carried about the little children and danced with them.’24

Through the study of Georgian dance, the Georgian Papers Programme at the Royal Archives have revealed a picture of George III as a loving family man, who loved children and dancing. We glean greater insight into the royal children, with brothers and sisters writing to each other in England and Hanover. Their personalities and relationships with their parents emerge, illuminating a familial love of music and dance (except for Princess Charlotte, the Princess Royal). The royal family facilitated the dissemination of English and European dance forms between England and Hanover, helping to spread the country dance, as well as cotillions, allemandes, waltzes, and quadrilles. They were proficient dancers, who were able to perform with grace and ease at the royal birthday balls, although they infinitely preferred their informal birthday balls to the courtly ceremony at St James’s Palace. While the royal family loved to dance for entertainment, they also understood the importance of dance in connecting with people across the country, with royal tours and progresses showing their attentiveness to fellow ball attendees. Dance was an essential accomplishment in Georgian Britain, one to be attained by the middling, nobility, and royal alike. Minuets and country dances were critical for communication and connecting with people, instrumental to creating and maintaining friendships and networks.

Footnotes

- Moira Goff, ‘Desnoyer, Charmer of the Georgian Age’, Historical Dance, 4/2 (2012), p. 7.

- Royal Archives, GEO/MAIN/36836-36948, Treasurer’s Accounts of Queen Charlotte’s Household, 1777-1793; GEO/MAIN/42839-42916, Accounts of George IV as Prince of Wales, 1783

- ‘The Queen’s Birth-Day’, Derby Mercury, 18 Jan. 1787; ‘Tuesday and Wednesday’s Posts’, Hereford Journal, 8 June 1791. See also ‘His Majesty’s Birth Day’, Reading Mercury, 8 June 1789;‘Queen’s Birth-Day’, Norfolk Chronicle, 22 Jan. 1785; ‘The Queen’s Birth-Day’, Derby Mercury, 18 Jan. 1787; ‘His Majesty’s Birth Day’, Reading Mercury, 8 June 1789.

- Flora Fraser, Princesses: the Six Daughters of George III (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), p. 38.

- Royal Archives, GEO/ADD/9/55, letter from Princess Royal to Prince Augustus, 26 Sept.1788.

- Anson Mss, A1, Princess Royal to Mary Hamilton, 18 June 1780.

- Royal Archives,GEO/ADD/9/36, letter from Princess Elizabeth to Prince Augustus, 19 August 1787.

- Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/43381-2, Letter from the Duke of York to the Prince of Wales, 9 February 1781

- Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/43399, letter from the Duke of York to the Prince of Wales, 24 March 1781; GEO/MAIN/43420-3, Letter from the Prince of Wales to the Duke of York, 11 May 1781.

- Royal Archives GEO/MAIN/43417, letter from the Duke of York to the Prince of Wales, 4 May 1781.

- M. Malpied, Traité sur l’Art de la Danse (Paris, 1770), pp. 94-8.

- ‘Court Intelligence’, Kentish Gazette, 9 June 1781.

- The European Magazine, and London Review, i (London, 1782), pp. 15-16.

- Royal Archives GEO/ADD/15/8160, letter from Queen Charlotte to Lady Charlotte Finch, 6 June 1782.

- Hanover Royal Music Archive, Beinecke Rare Book and Music Library, Yale University, OSB MSS 146 Music Book, 1787-1789.

- Royal Archives GEO/ADD/46/4, Letter from Princess Augusta to Mrs. Louisa Cheveley, December 1802; L. M. Middleton, ‘Parsons, Sir William (1745/6–1817), musician and composer,’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/21480; Thomas Busby, Concert room and orchestra anecdotes of music and musicians, vol. 1 (London, 1825), pp. 265-6.

- ‘The Queen’s Birth-Day’, Derby Mercury, 18 Jan. 1787.

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, OSB MSS 146.

- Royal Archives GEO/ADD/9/40, letter from Princess Royal to Prince Augustus, 28 Nov. 1787.

- Royal Archives GEO/ADD/9/152, Letter from Princess Augusta to Prince Augustus, 10-21 November 1791.

- Royal Archives GEO/ADD/11/9, Letter from Princess Elizabeth to Prince Augustus, 30 July 1791.

- Mary Frampton, The Journal of Mary Frampton, from the year 1779, until the year 1846, 2nd edn, edited by Harriot Georgiana Mundy (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1885), pp. 120-2.

- Frampton, Journal, 123.

- Frampton, Journal, 123-4.