Dragons in the Dressing Room: St. George and Female Morality

By Sarah Donovan, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

In the opening years of the nineteenth century, the ceiling of the Queen’s dressing room in Windsor Castle depicted the trials and tribulations of St. George as he labored to protect female chastity from the clutches of tyrants.[1] This mural expresses the enduring fascination with St. George among Englishmen since the medieval period.

Saint George and the Dragon, Paolo Uccello (1397-1475), The National Gallery, London, Accession no. NG6294

St. George of Cappadocia was a Christian martyr killed in the latter half of the third century. One of St. George’s most famous feats was his battle with an unidentifiable kind of monster, later depicted in art as a dragon.[2] St. George joined the pantheon of martyrs that became increasingly revered from the fourth century onward. He was a particularly popular saint in fifteenth century England as King Edward I invoked his spiritual protection over the English Army.[3] These consistent invocations of St. George by English monarchs throughout the centuries propelled him to be declared the patron saint of England. The appeal of St. George to pious English men and women was so powerful that his legacy remained despite the religious upheaval of the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century, St. George’s feast day, April 23, was revered as both a day of holy obligation among English Catholics and as a national holiday by English Protestants. As a national legend, St. George seems a logical choice to adorn the ceilings of the Windsor Castle. However, the placement of such a mural in the Queen’s dressing room has a deeper meaning.

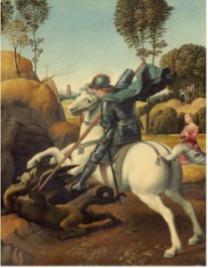

Saint George and the Dragon c. 1506, Raphael (1483-1520), Andrew W. Mellon Collection, Accession no. 1937.1.26

Dressing rooms were a private and exclusively female space where women were able to act independently.[4] Focusing on the privacy and exclusivity of this space, eighteenth century literature characterized dressing rooms as provocative and sexual venue for intrigue and debauchery.[5] Jonathan Swift was among these contemporary satirists and authors who considered the dastardly deeds that could happen behind the closed doors of a lady’s dressing room. Swift’s poem, A Lady’s Dressing Room, cautions that dirty truths may lie beneath a lady’s beautiful exterior.[6] These eighteenth-century writers such as Swift make explicit connections between dressing rooms and larger concerns regarding female morality. While authors such as Swift cautioned that dressing rooms were the seat of indecency and immorality, other men trusted that women would behave behind closed doors and continue to be good and just mothers and wives. Nevertheless, the act of closing the dressing room door inevitably added an element of mystery to male onlookers speculating about female behavior.

The placement of a mural depicting St. George defeating the dragon and protecting female chastity on the ceiling of the Queen’s dressing room in Windsor Castle has layered meaning. The choice to place such a revered figure in English history on the dressing room ceiling demonstrates the Queen’s historical awareness and her personal connection to previous monarchs, such as King Edward I, who invoked St. George for protection. However, coupled with the literary discourse surrounding lady’s dressing rooms, the depiction of St. George vowing to “destroy the Dragon and deliver her [a woman in distress] from his fangs,” seems to serve as a reminder of the patriarchal duty of men to protect female virtue.[7] When painted on a dressing room ceiling, perhaps the dragon represents the immorality and wickedness that men such as St. George were obliged to vanquish.

The placement of a mural depicting St. George defeating the dragon and protecting female chastity on the ceiling of the Queen’s dressing room in Windsor Castle has layered meaning. The choice to place such a revered figure in English history on the dressing room ceiling demonstrates the Queen’s historical awareness and her personal connection to previous monarchs, such as King Edward I, who invoked St. George for protection. However, coupled with the literary discourse surrounding lady’s dressing rooms, the depiction of St. George vowing to “destroy the Dragon and deliver her [a woman in distress] from his fangs,” seems to serve as a reminder of the patriarchal duty of men to protect female virtue.[7] When painted on a dressing room ceiling, perhaps the dragon represents the immorality and wickedness that men such as St. George were obliged to vanquish.

Whether the Queen’s mural of St. George is simply a nod to English tradition or a veiled attempt to display patriarchal values within the private, female-only space of the dressing room, a dragon in a dressing room is certainly a curious sight!

[2] David Howell, “St. George as Intercessor,” Byzantion 39, (1969): 121.

[3] Jonathan Good, “Popular t. George in Late Medieval England,” in The Cult of St. George in Medieval England, (Boydell Press, 2009), 96.

[4] Tita Chico, Designing Women: The Dressing Room in Eighteenth-Century English Literature and Culture, (Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 2005), 9.; See also, Tita Chico, “Privacy and Speculation in Early Eighteenth-Century Britian,” Cultural Critique, no. 52 (Autumn 2002): 40-60.

[5] Chico, Designing Women, 10-11.

[6] Jonathan Swift, the Lady’s Dressing-Room. A Poem. By ********, (Dublin, 1732).