Foul Play in the House of Commons: The Murder of Spencer Perceval

By Sarah Donovan, William & Mary

Welcome back to our Georgian Goodies blog series, where we highlight interesting, timely, or just plain nifty documents from the Georgian Papers Programme!

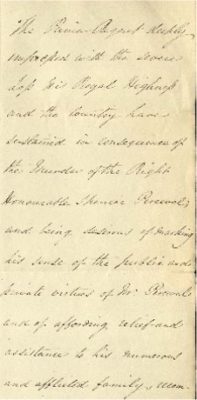

In 1812, Prince Regent George drafted a public statement commenting on “the severe Loss His Royal Highness and the Country have sustained in consequence of the Murder of the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval.”[1]

In 1812, Prince Regent George drafted a public statement commenting on “the severe Loss His Royal Highness and the Country have sustained in consequence of the Murder of the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval.”[1]

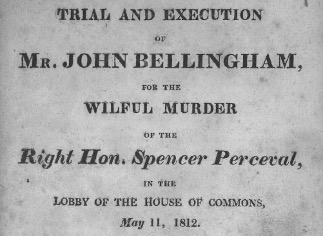

On the evening of May 11, 1812, John Bellingham walked into the lobby of the House of Commons and shot Prime Minister Spencer Perceval through the heart. After the deed was committed, Bellingham did not try to escape and willingly admitted to the crime.[2] Bellingham was put on trial four days later where he was convicted for willful murder and executed on May 18, 1812.[3] As the prime minister leading the British Parliament through the troubling international conflicts of the early nineteenth century, Perceval’s loss had the potential to transform the political landscape. However, what was most interesting about this case was not the political repercussions, but rather Bellingham’s motivations for committing the crime.[4]

Bellingham struggled with finances throughout his adult life. Bellingham established his merchant career in London before moving to Russia to serve under a merchant in Archangel. In 1804, Bellingham lost a ship of merchandise off the shore of Russia. Shortly afterwards, Bellingham was accused of insurance fraud.[5] These events plunged Bellingham deeply into debt, originally totaling nearly 38,000 roubles. While Bellingham did not believe he owed any money, he was able to negotiate his debts down to approximately 2,000 roubles but remained imprisoned for non-payment of his debts. After five years of negotiations, Bellingham was finally able to leave Russia without settling his debts.[6] After leaving Russia, petitioning the British government for redress became Bellingham’s full-time job.[7] By 1812, Bellingham’s frustration had become too much, and he resolved to act. Bellingham’s murder of Perceval was not politically motivated but was the culmination of Bellingham’s frustration with the British government.

Bellingham struggled with finances throughout his adult life. Bellingham established his merchant career in London before moving to Russia to serve under a merchant in Archangel. In 1804, Bellingham lost a ship of merchandise off the shore of Russia. Shortly afterwards, Bellingham was accused of insurance fraud.[5] These events plunged Bellingham deeply into debt, originally totaling nearly 38,000 roubles. While Bellingham did not believe he owed any money, he was able to negotiate his debts down to approximately 2,000 roubles but remained imprisoned for non-payment of his debts. After five years of negotiations, Bellingham was finally able to leave Russia without settling his debts.[6] After leaving Russia, petitioning the British government for redress became Bellingham’s full-time job.[7] By 1812, Bellingham’s frustration had become too much, and he resolved to act. Bellingham’s murder of Perceval was not politically motivated but was the culmination of Bellingham’s frustration with the British government.

Although his motivations were personal, Bellingham’s trial sparked a national debate over insanity in the criminal process. Both the prosecution and defense brought Bellingham’s mental stability to the forefront of the trial. Mr. Abbott, representing the prosecution, questioned the standards of insanity in criminal charges, writing “must he be of necessity be insane, because he had devised a deed so horrid, wicked, and atrocious, as no other person could be found capable of projecting?”[8] Conversely, Anne Billet, a witness called for defense, supported accusations of Bellingham’s insanity. Billet argued that Bellingham “always appeared to her to be deranged when he spoke of his affairs in Russia…[and] exhibited strong marks of insanity.”[9] Although Bellingham’s insanity was central to the defense’s argument, Bellingham himself did not plead insanity in his personal statement. Ultimately, Bellingham was deemed mentally stable and found guilty of murder, but these questions of mental stability were especially important as King George III struggled with his mental health in the end of the eighteenth century.[10]

Although his motivations were personal, Bellingham’s trial sparked a national debate over insanity in the criminal process. Both the prosecution and defense brought Bellingham’s mental stability to the forefront of the trial. Mr. Abbott, representing the prosecution, questioned the standards of insanity in criminal charges, writing “must he be of necessity be insane, because he had devised a deed so horrid, wicked, and atrocious, as no other person could be found capable of projecting?”[8] Conversely, Anne Billet, a witness called for defense, supported accusations of Bellingham’s insanity. Billet argued that Bellingham “always appeared to her to be deranged when he spoke of his affairs in Russia…[and] exhibited strong marks of insanity.”[9] Although Bellingham’s insanity was central to the defense’s argument, Bellingham himself did not plead insanity in his personal statement. Ultimately, Bellingham was deemed mentally stable and found guilty of murder, but these questions of mental stability were especially important as King George III struggled with his mental health in the end of the eighteenth century.[10]

In the verdict, the jury lamented the loss of Perceval and charged Bellingham arguing, “you robbed charity of one of its warmest patrons; religion, of one of its firmest supporters; domestic life of, of one if its brightest ornaments.”[11] Regardless of Bellingham’s mental state, the loss of Spencer Perceval was a shock to the royal family. Queen Charlotte wrote to George Prince Regent, “I only grieve that the Execution could not have [taken] place immediately after the Condemnation.”[12] The speedy trial of Bellingham and his execution provided justice to his family and his community.

[2] Kathleen S. Goddard, “A Case of Injustice? The Trial of John Bellingham,” The American Journal of Legal History 46, no. 1 (January 2004): 3.

[3] Gordon Pentland, “’Now the great Man in the Parliament House is dead, we shall have a big Loaf!’ Responses to the Assassination of Spencer Perceval,” Journal of British Studies 51, no. 2 (April 2012): 344.

[4] Pentland, “’Now the great Man in the Parliament House is dead, we shall have a big Loaf!’” 341.

[5] Goddard, “A Case of Injustice?” 4-5.

[6] Goddard, “A Case of Injustice?” 5.

[7] Pentland, “’Now the great Man in the Parliament House is dead, we shall have a big Loaf!’” 343.

[8] Trial and Execution of Mr. John Bellingham for the Willful Murder of the Right Hon. Spencer Perceval, in the Lobby of the House of Commons, (21 Boar-Lane, London: B. Dewhirst, 1812) 8.

[9] Trial and Execution of Mr. John Bellingham for the Willful Murder of the Right Hon. Spencer Perceval, in the Lobby of the House of Commons, (21 Boar-Lane, London: B. Dewhirst, 1812) 23.

[10] See exhibit by Arthur Burns and Karin Wulf: https://georgianpapers.com/explore-the-collections/virtual-exhibits/george-iii-the-eighteenth-centurys-most-prominent-mental-health-patient-a-virtual-exhibition-by-arthur-burns-and-karin-wulf/

[11] Trial and Execution of Mr. John Bellingham for the Willful Murder of the Right Hon. Spencer Perceval, in the Lobby of the House of Commons, (21 Boar-Lane, London: B. Dewhirst, 1812) 25.