Mark Gatiss, Arthur Burns and Oliver Walton take a break half way through the exhibition!

The King’s episode of mania in 1788-89 should be seen in light of the fuller context of the royal family, the court, and the politics of the day. An affectionate and curious group, King George, Queen Charlotte and their children were interested in literary culture and scientific issues. Although the King’s treatment seems harsh from our contemporary perspective, he and his family were quite interested in medicine, including new experimental treatments that we would regard as forward-thinking such as vaccination.

George III’s illness was directly relevant to the vital questions of succession and rule. Materials in the Georgian Papers show that both were never far from a king’s mind, or those of his family and ministers. The expectation was that the Prince of Wales would succeed to the throne after his father’s death, but the issue of the king’s incapacity, first raised during the crisis of 1788-89, raised the prospect that he would achieve effective power in advance of this eventuality. Discussions of a regency began, but were put on hold as the King recovered. In late 1810, following the death of his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia, the King was again afflicted. Under the Regency Act of 1811 the Prince of Wales acted in his father’s stead (as the Prince Regent) until the latter’s death in 1820, at which point he was crowned King George IV.

8. The Royal Family and ‘modern’ medicine

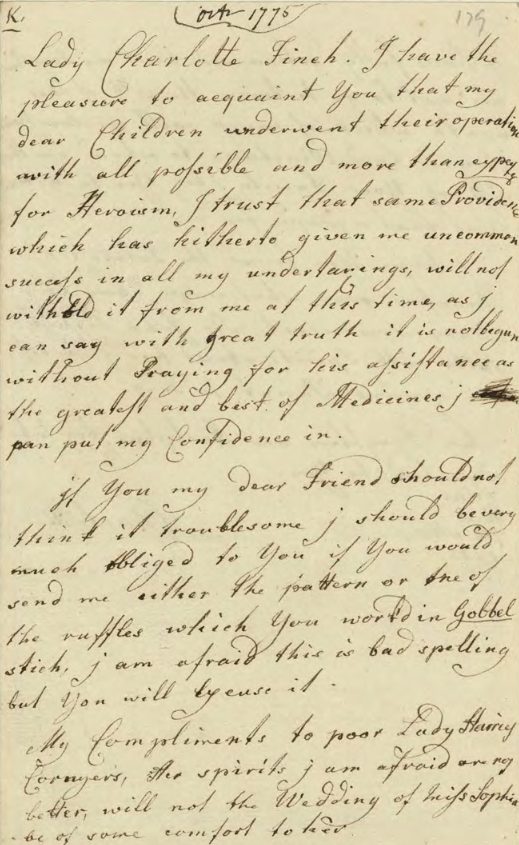

Letter from Queen Charlotte to Lady Charlotte Finch, 7 October 1775

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/15/8157

The recourse to Dr Willis was not the only occasion on which the royal family showed itself willing to engage with medical approaches which had uncertain outcomes, and sometimes significant risks.

To read on in a high resolution image, click on the document. For a typed transcription, click here. For the catalogue entry, click here.

Smallpox was one of the most unpleasant diseases that our ancestors faced, not only for its disfiguring consequences, but for the high risk of mortality that accompanied it. During the eighteenth century, some 400,000 Europeans each year succumbed to the disease. It was no respecter of persons: among its victims were Queen Mary II of England, Emperor Joseph I of Austria, King Luis I of Spain, Tsar Peter II of Russia, Queen Ulrika Elenora of Sweden, and King Louis XV of France. Its virulence saw it adopted in effect as a biological weapon by the British during the siege of Fort Pitt in the Seven Years War/French and Indian Wars (1756-1763) against France’s Native American allies.

This letter was written to the royal governess, Lady Charlotte Finch (1725-1813), by Queen Charlotte with news of the inoculation of some of her children. This was before Edward Jenner developed his vaccination with cowpox to prevent the disease at the very end of the century. The process involved here was a riskier and more unpleasant one, ‘inoculation’ or ‘variolation’, in which infected matter was pulled on a thread under the skin on both arms via incisions made with a lancet, the patient then being sent to bed for some days until the disease showed itself. Lady Finch had to be written to since, not having had smallpox herself or an inoculation, it was judged too dangerous for her to be in attendance when the operation took place, although we know that she had earlier nursed the prince of Wales and the duke of York after they had undergone the operation. The procedure had reached England through the advocacy of Lady Mary Wortley Montague, a smallpox victim herself, in the second decade of the century after she had encountered it while resident in Istanbul; in 1722 the operation was successfully performed on daughters of the Princess of Wales, after which it gained popularity at court and beyond. The operation nevertheless was a risky one: it reduced rather than eliminated the danger of mortality from the deliberately induced infection. In 1782, the one-year-old Prince Alfred would die after his inoculation; six months later the four-year-old Prince Octavius also died in the wake of his treatment. Knowing what was to come gives additional poignancy to Charlotte’s comments here about trusting in Providence for the outcome of the process rather than the medical procedure itself. These comments also, however, underline the importance of the royal family’s religious beliefs in enabling them to cope with the losses both personal and political that punctuated George’s reign, even when they were stricken with grief: on the 23 December 1788 in his delirium the King clung to his pillow in bed, calling it Octavius, and saying ‘he would be new born that day’. It is perhaps no wonder, nevertheless, that the King later backed Jenner’s petitions for financial support for his new approach in the first years of the nineteenth century.

9. The stuff of politics

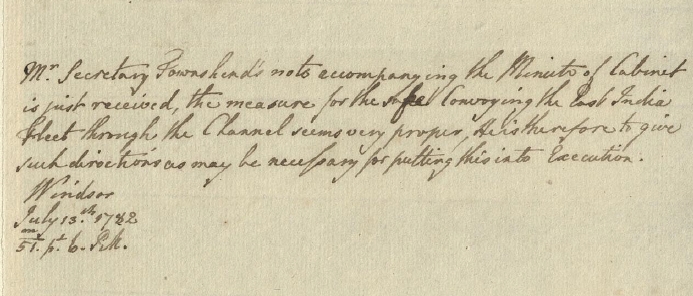

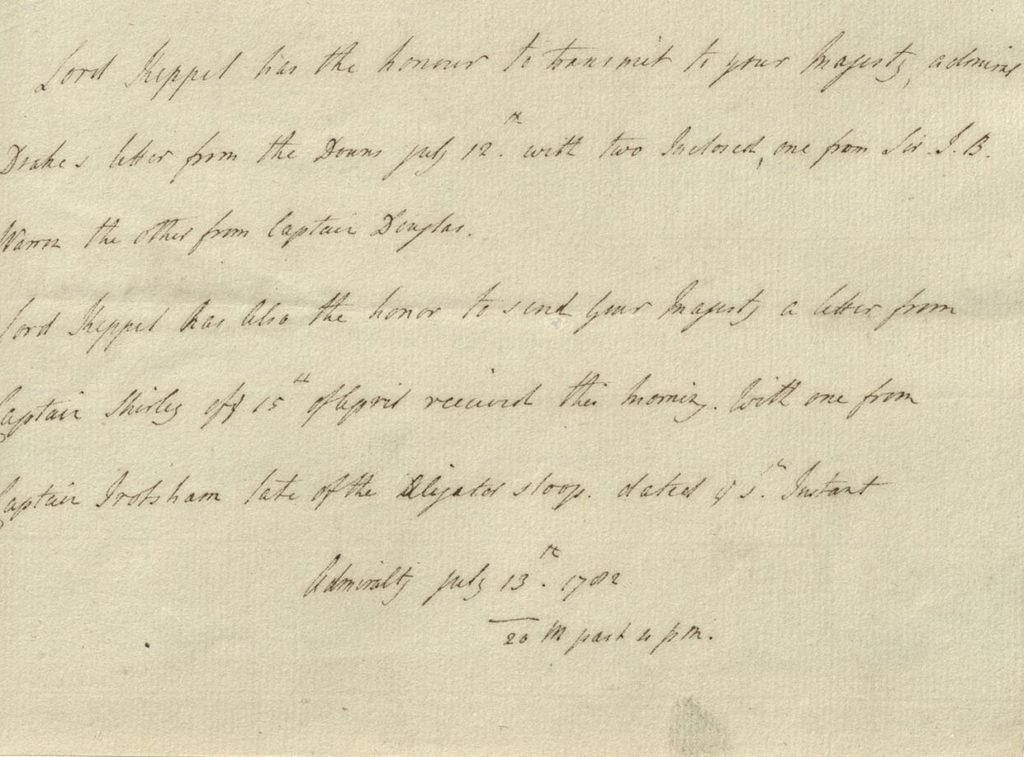

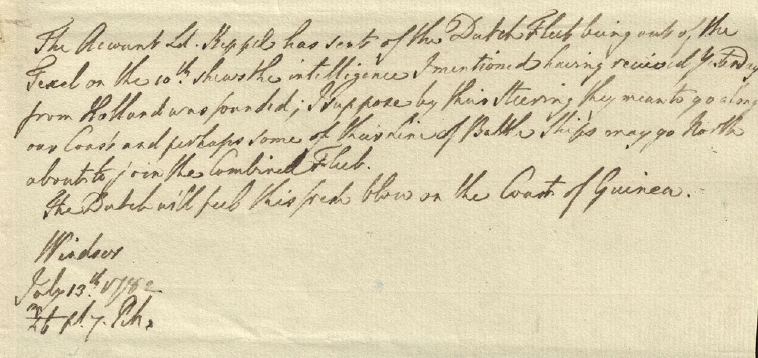

Letters between George III and politicians from 13 July 1782

Georgian papers, GEO/MAIN/4857-61

To read the full correspondence and to see a high-quality image, click on the document. Hard to read? For a typed transcription, click here.

These documents offer an insight into the frenetic conduct of politics which forms so important a part of the setting for the king’s illness in The Madness of George III. We are accustomed to thinking that life has accelerated; and of course in certain contexts in the eighteenth century events could unfold with to modern eyes astonishing slowness, as for example when British leaders had to react to developments in North America weeks after they had taken place, and had then to wait further weeks before their representatives on the ground could take account of their response.

To read the full correspondence and to see a high-quality image, click on the document. Hard to read? For a typed transcription, click here.

To read the full correspondence and to see a high-quality image, click on the document. Hard to read? For a typed transcription, click here.

In London, on the other hand, politics could be conducted with remarkable rapidity, as messengers conveyed the post across the capital and beyond with the same urgency displayed today by cycle couriers. Consequently, when the interested parties did not meet, several iterations could take place in the course of what was often a long single day. As one of our GPP fellows, Andrew Beaumont, has noted, there were numerous respects in which such transactions, although on paper, could resemble our current use of email, complete with attachments (enclosures), time stamps, multiple copies of messages winging their way across the metropolis, and archiving.

These exchanges show the king’s involvement in a typical exchange of correspondence from a single day: 13 July 1782, when Lord Shelburne had assumed the role of Prime Minister following the sudden death of the Marquess of Rockingham on the first of the month. At 3 p.m. Thomas Townshend, secretary of state for the Home Department, had forwarded a cabinet minute of the previous day written by Viscount Keppel, first lord of the admiralty, recommending fleet movements to the king; at 6.51 p.m. the king replied, drafting his letter on a page of Townshend’s. Keppel himself had written at 4 p.m. with copies of key naval correspondence; once more the reply, penned at 7.46 p.m., was drafted on the letter to which it replied. In passing, these letters also highlight the time-lag for more distant correspondence — Keppel passes on a letter received that morning dated 15th of April from Captain Thomas Shirley, operating in the ship Leander off the West African coast, as well as one from the captain of the Alligator, a ship shortly after to suffer the ignominuous fate of being captured by the French and deployed under their colours.

At some point during the day the King had also written to Charles Jenkinson, an asset to any administration, asking him to lend his support to the ministry; Jenkinson wrote his reply at midnight in his residence at Addiscombe Place in Croydon.

We can date these exchanges so precisely to the minute because the king and his ministers routinely dated them to the minute. It is also clear that this habit gave George the capacity to track back through his correspondence to reconstruct the timing of his interventions on key issues of controversy, to the end of allowing him to justify his own conduct to others, and perhaps himself and his conscience, as above reproach.

10. A happy marriage and the social whirl

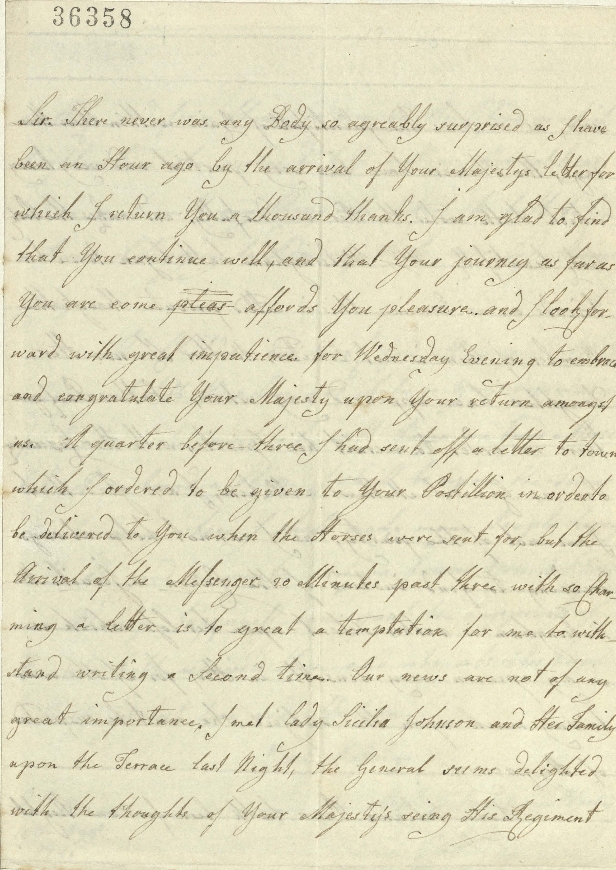

Letter from Queen Charlotte to George III, 13 August 1781

Georgian papers, GEO/MAIN/36358-9

Click on the document image to read the full letter in a high-resolution image. Click here for a typed transcription, and here for the catalogue entry.

There is nothing especially out of the ordinary about this letter — and that is the point. Queen Charlotte is writing to George III as he returns from a trip sailing from Greenwich to inspect the fleet and defences at the Nore, one of the key naval installations on the east coast (it should be remembered that, for all his global concerns, George III was one of the least travelled royals in modern British history, never venturing north of Worcester, or south of Weymouth).

The letter is typical of her writing to the monarch, other family and friends in its combination of warmth, gossip, and news, in this case of people encountered on the Terrace at Windsor, where so many conversations between the royals and others took place. Here Queen Charlotte mentions Lady Cecilia Johnson (as an ageing fashionable society hostess a frequent subject of James Gillray, the satirical cartoonist — for one example in the National Portrait Gallery, see here). Her letter also conveys gossip about Charlotte Walshingham, apparently now re-entering society after her husband, the Irish MP and naval commodore Robert Boyle Walshingham, had been drowned along with his entire crew when his 74-gun ship the Thunderer had foundered in a Caribbean hurricane off San Domingo on 5 October 1780. The Queen also has news of Lady Juliana Fermor Penn of Stoke Park, Buckinghamshire (1729-1801), widow of Thomas Penn, proprietor of the colony of Pennsylvania, and daughter of the 1st Earl of Pomfret and so sister not only of Henrietta Conyers (who is here called Harriot) of Copped Hall, Essex and mentioned in the letter, but also of Lady Charlotte Finch, the royal governess to whom the Queen’s letter above (item 8) was addressed. With the additional mention of Admiral John Forbes, the letter thus conveys something of the social world of the royal couple at court, with its military men and aristocratic women with many transatlantic connections.

There is no hint in this letter that English was a second language for the Queen — indeed the only stilted aspect to our eyes is in the odd combination of conjugal affection and due deference to the sovereign. For above all this affectionate letter encapsulates the close bond between Queen Charlotte and her husband: it shows how the formality of addressing George III as ‘Your Majesty’ was not an impediment to intimate and lively exchanges of views and feelings.

11. The Loss of America — and after: George III reflects

Essay on America and future colonial policy, [1784?]

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/32/2010-11

Click on the image of the document to see a high-resolution image and to continue reading. Click here for a typed transcription, and here for the catalogue entry.

In Bennett’s play, the loss of the American colonies, effectively settled by the British defeat at Yorktown in 1781 and then peace negotiations culminating in the Treaty of Versailles of 1783, forms part of the background to the events portrayed. The King displays his own sense of loss, while the earlier divisions over policy towards America complicate his relations with his politicians, especially Charles James Fox. As Andrew O’Shaughnessy, one of our GPP Sons of the American Revolution Visiting Professors has recently reminded us in his magisterial The Men who Lost America: British Command during the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire (2013), George had invested much in his efforts to prevent the loss of the colonies and had followed developments closely, and there is no doubt that the defeat was a major blow quite apart from the complications it caused for his domestic ambition of securing a stable government.

The document before us presents a new and perhaps surprising perspective on the king’s response to the loss of America, and is a good example of the discoveries now arising from the Georgian Papers Programme. It is found among some 8,500 pages of prose pieces, fragments, duplicates and notes on a very wide range of subjects and largely undated, which the Programme has grouped as ‘the Essays of George III’, and which are among those parts of the archive which have previously attracted little interest from scholars. They have all been digitized and published on our webpages, and have also been transcribed to enable indexing and searching. We are currently collectively engaged in work on both sides of the Atlantic to establish how best to understand the nature of these documents and how best to approach them, this work being led by Jenny Buckley, currently a doctoral student at the University of York. They are clearly central to any attempt to understand in what sense George III could be described as an ‘enlightened monarch’, and what the key influences on his thought and actions as a ruler were, but do not offer easy answers!

The case of the ‘America is Lost’ essay offers a good example of the questions they raise, and because of its particular subject matter has already attracted the attention of the Programme’s researchers, links to their commentaries being found at the end of this entry. It is certainly written in George’s own hand, but it is also clear on closer inspection that it is not his original composition. Our researchers have identified the text as a ‘near verbatim’ extract from a much longer essay published by the English agricultural writer Arthur Young in his magazine Annals of Agriculture in 1784, a year after American Independence had finally been conceded. However, it does not merely reproduce the published article. Although it might be a copy of an earlier draft (we know that George III corresponded with Young and even wrote for the Annals himself under the pseudonym of Ralph Robinson, so this is not completely implausible) it was most probably ‘commonplaced’ – that is extracted from the published version – and re-framed by the King as an exploration of the issues. In either case, the document offers a tantalising view of the King’s thoughts and feelings after the loss of the American colonies, for the differences between the ‘essay’ and Young’s published text serve to present a more optimistic view of the consequences for Britain’s future.

In doing this, it reinforces the sense that for all the pain and frustration George experienced over the loss of the colonies, he nevertheless found ways ultimately to reconcile himself to this turn of events. Regardless of the economic consequences, George’s strong religious beliefs would in any case have led him to view the outcome, whatever it was, as the workings of a divine providence, something which as we see elsewhere in this exhibition helped him to cope with a range of setbacks, just as it did with Charlotte and the children’s innoculations.

12. The King in peril

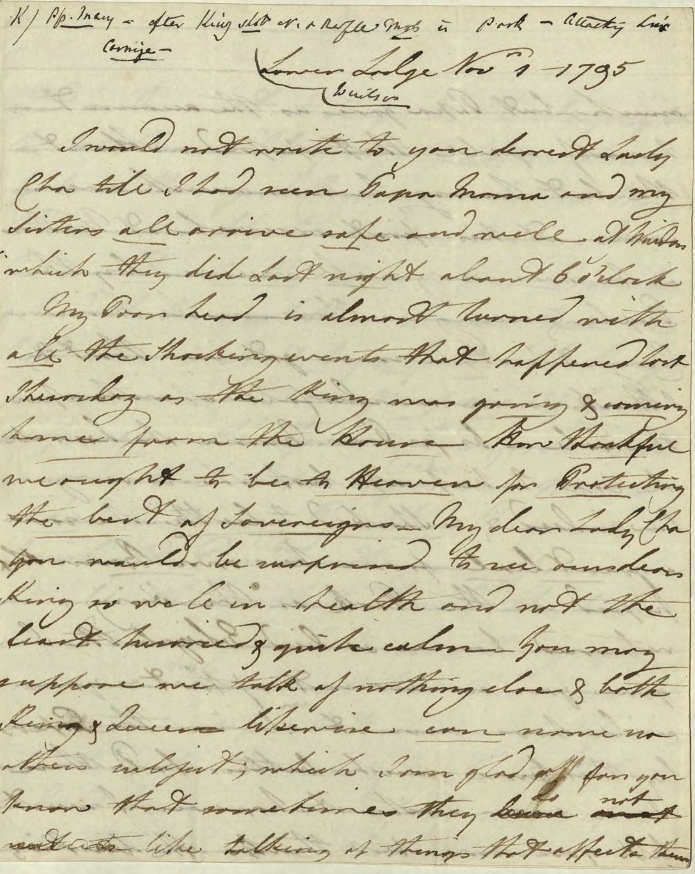

Letter from Princess Mary to Lady Charlotte Finch, 1 November 1795

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/15/8167

Click on image to read in full and high definition; for a typed transcript click here, and here for the catalogue entry.

No one watching Bennett’s play has ever been unmoved by the plight of the King, and if so, that is partly on account of the impression it gives of the King’s own response to his affliction. Similarly, anyone reading George’s papers cannot but be struck by the way in which this clearly emotional man withstood so many blows both personal and political over the course of his long reign before illness finally defeated him, and by his personal courage in moments of crisis. The letter before us both hints at how George dealt with reversals of fortunes and also testifies to the genuine bonds of affection that bound his immediate family.

In 1795, there was a great deal of unrest in the country as both the war and food shortages hit the population at large, and protests followed. On 29 October George III was assailed by a mob as he travelled to open parliament in his carriage. The glass of the window was pierced, either by a bullet or a stone. This was one of several occasions in his reign on which his life was genuinely imperilled (there were also serious assassination attempts in 1786 and 1800). This letter, written by the 21-year-old Princess Mary to her former governess, Charlotte Finch, recounts the immediate reaction of the King’s family to the incident. No doubt in the back of their minds was the recent fate of the French royal family in the Revolution.

Several things emerge clearly, not least the genuine emotions on display in the family: the love of the princess for her father, the Queen’s shock at the incident and the King’s own distress immediately after it. Like the earlier letter from the Queen, these indicate that the famous domesticity of George III was more than a myth, underlining the pain that must have been caused by the King’s illness, in particular to Charlotte.

We also see that the King soon recovered himself, just as Bennett suggests in his treatment of one of the other attacks on the monarch, that by Margaret Nicholson, which actually took place rather earlier than Bennett suggests, in 1786. His exchanges both with the family and with the Lord Chancellor as recorded here also speak to the importance of his belief in divine providence, ‘Man proposes and God disposes’, which he shared not only with his wife but with his daughters, in enabling him to absorb severe blows and shocks. George’s piety, in an age in which Methodism and evangelicalism were both spreading across the population and with them bringing more open displays of religious ‘enthusiasm’, was restrained in its expression. But it was no less important as a firm foundation of his approach both to his family life and his public duties.

13. The King and the Prince of Wales — eight years on

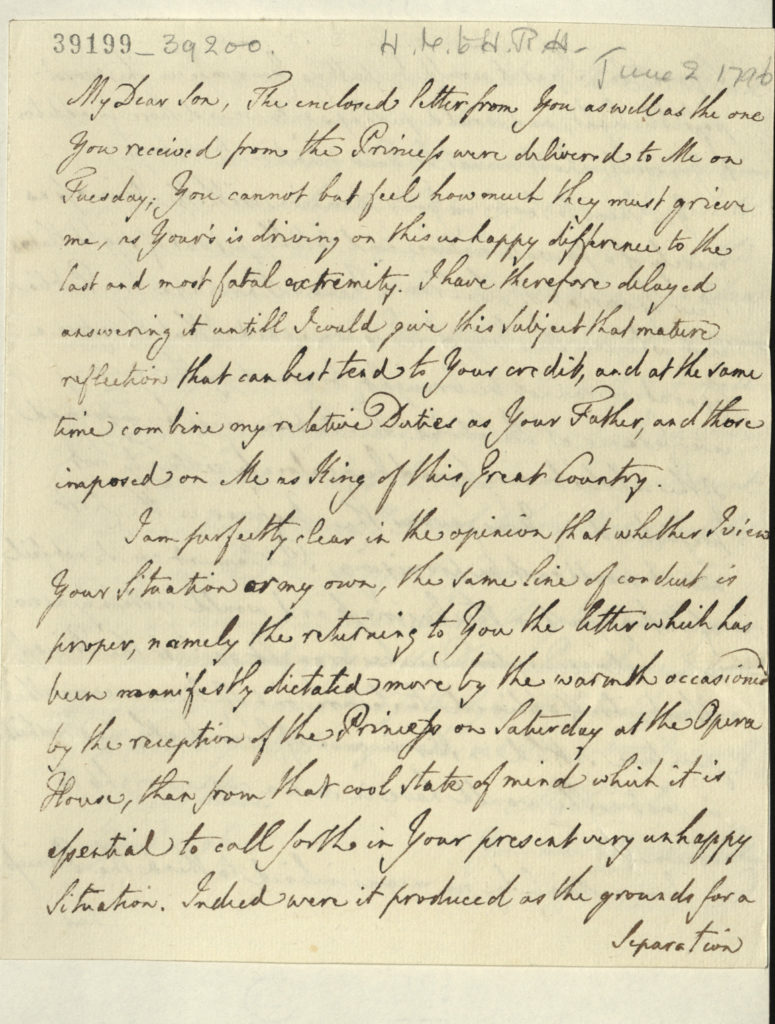

Letter from George III to George, Prince of Wales 2 June 1796

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/39199-200

Click on the document to read on in a high resolution image. For a typed transcription click here.

The Madness of George III concludes with the audience cheered by the King’s recovery in 1789, pleased that, in the last words given to George in the stage version, ‘The King is himself again’, and enjoying the Prince of Wales’s come-uppance. Anyone aware of the subsequent history of the King and his son, however, knows that their stories both had long and often unhappy courses still to run.

In this letter from June 1796 we catch a glimpse of the play’s protagonists eight years on. The situation of the Prince of Wales has changed significantly. A year before he had married Caroline of Brunswick, as part of a deal under which the King undertook (again!) to relieve him of his debts, which now amounted to £630,000 (almost £60 million in modern equivalance). In January the union had produced Princess Charlotte: family letters from this period occasionally reveal the King’s daughters expressing delight over the new arrival and their brother’s appearance in the new role of pater familias. Alas, the ill-fated match had already begun to disintegrate, with the couple separating in the course of 1796 and the Prince focusing again on Maria Fitzherbert as his ‘true’ wife , whom he had secretly if illegally married in 1785.

This letter responded to one from the Prince written after his wife had paid a visit to the Royal Opera House at the end of May, when the audience had responded to her presence and the rumours doing the rounds about the marriage by standing to cheer her. With the Prince and Princess competing with each other to win the King to their side, the prince had argued to his father that the displays of support for Caroline were the work of a party who aimed to damage the monarchy as a whole (thus echoing the argument he had deployed in the Regency crisis to defend his conduct then — see item 6), calling on the king to take a robust stand lest the monarchy suffer the fate of that in France.

The King’s letter makes clear that his son’s argument and demand for a separation had fallen on deaf ears, and indeed shows him insisting it be regarded as an angry over-reaction to press coverage of the Opera incident attacking the Prince, rather than as a rational response. As well as illustrating how difficult the relation of King and heir remained, the letter is also striking for its clear assessment of the context in which the monarchy had to operate at the end of the eighteenth century. While conceding that the Prince is not the only one at fault, the King is under no illusions that the court of public opinion will condemn the Prince for his behaviour, and that this will ensure that parliament will not help the Prince achieve his aims. In this opinion we both see a clear-eyed recognition of the increased role of the public in political life, and also the King’s own sense that the royal family must be governed by their sense of duty to ‘this great Country’ and its people in regulating not only their public but their private conduct. That he is not confident that his son will respond to this line of reasoning is apparent from the invocation of Providence in the closing lines of the letter. As Bennett’s King puts it to the Prince of Wales in their last encounter in the play:

KING: For the future, we must try to be more of a family. There are model farms now, model villages, even model factories. Well, we must be a model family for the nation to look to.

END OF THE EXHIBITION

Thank you for visiting the Georgian Papers virtual The Madness of George III exhibition.

If you have enjoyed the Exhibition and would like to follow the progress of the Programme, you can keep track of this exciting project by joining the King’s Friends. Membership is free, and Friends receive regular newsletters (find out more here). You can also follow us on Twitter. And if you found the handwriting in these documents an enjoyable and challenging puzzle, there will shortly be opportunities to join in the task of transcribing some of the remaining 400,000 pages to make them more accessible to all. Again, follow us on Twitter to learn more.

You can read our reflections on Bennett’s play and its relation to academic history in the Programme for the Nottingham Playhouse production. You might also enjoy our exhibition related to Hamilton: An American Musical.

All images supplied by the Royal Archives and © Her Majesty the Queen 2016-18.

Exhibition Credits

Virtual and physical exhibitions devised and compiled by

Arthur Burns Academic Director, Georgian Papers Programme, Kings College

London

Karin Wulf North American Academic Director, Georgian Papers Programme,

Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, William & Mary

Oliver Walton Georgian Papers Programme Coordinator, Royal Archives

Technical assistance: Sam Callaghan, King’s College London, and Sara Belmont, William & Mary

Drawing on research, assistance and commentaries by the entire Georgian Papers Programme team of archivists, historians and cataloguers. Special thanks to Helen Esfandiary, Andrew Beaumont and Jenny Buckley.

Hosts for the physical Exhibition:

For the Royal Archives

Oliver Urquhart Irvine The Queen’s Librarian and Assistant Keeper of the Royal Archives

Bill Stockting Archives Manager, Royal Archives

Oliver Walton Georgian Papers Programme Coordinator, Royal Archives

Sarah Davis Head of Media Relations, Royal Collection Trust

Katie Buckhalter Assistant Press Officer, Royal Collection Trust

Ben Fitzpatrick Photographer, Royal Collection Trust

For the Georgian Papers Programme

Arthur Burns Kings College London

Karin Wulf Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, William & Mary

More information about the Programme can be found on this website.

More information and the currently digitized material can be found on the Royal Archives site: royalcollection.org.uk/collection/georgian-papers-programme