George III by Allan Ramsay, c.1761-1762 ©

Miscellaneous and Undated

The private papers of George III consist of, but are not limited to, documents and correspondence concerning George III’s personal and family life. The papers contain several different collections, the largest of which has been labelled ‘miscellaneous and undated’. This consists of a very wide range of documents, spanning the period 1755 to 1810. While primarily non-governmental correspondence both written to and about family members and European aristocracy, mostly by George III, the collection also features inventories, recipes, notes, petitions, memoranda, travel plans, drawings and medical reports.

Documents dating from before George III’s coronation in 1761 are scarce in comparison with the rest of the collection and it is these papers which best suit the title ‘miscellaneous’, containing anonymous recipes and architectural designs. There are also several notes written by George III which appear to be linked to his education. Some are religious in nature, while others relate to military history and the arts.

The collection includes a number of documents from the time of the death of his father, Frederick, Prince of Wales. George III wrote interesting analyses of the aftermath, giving an interesting and fairly comprehensive insight into the political sphere of the time. There is also correspondence from his grandfather George II, addressing George III’s bright future as monarch.

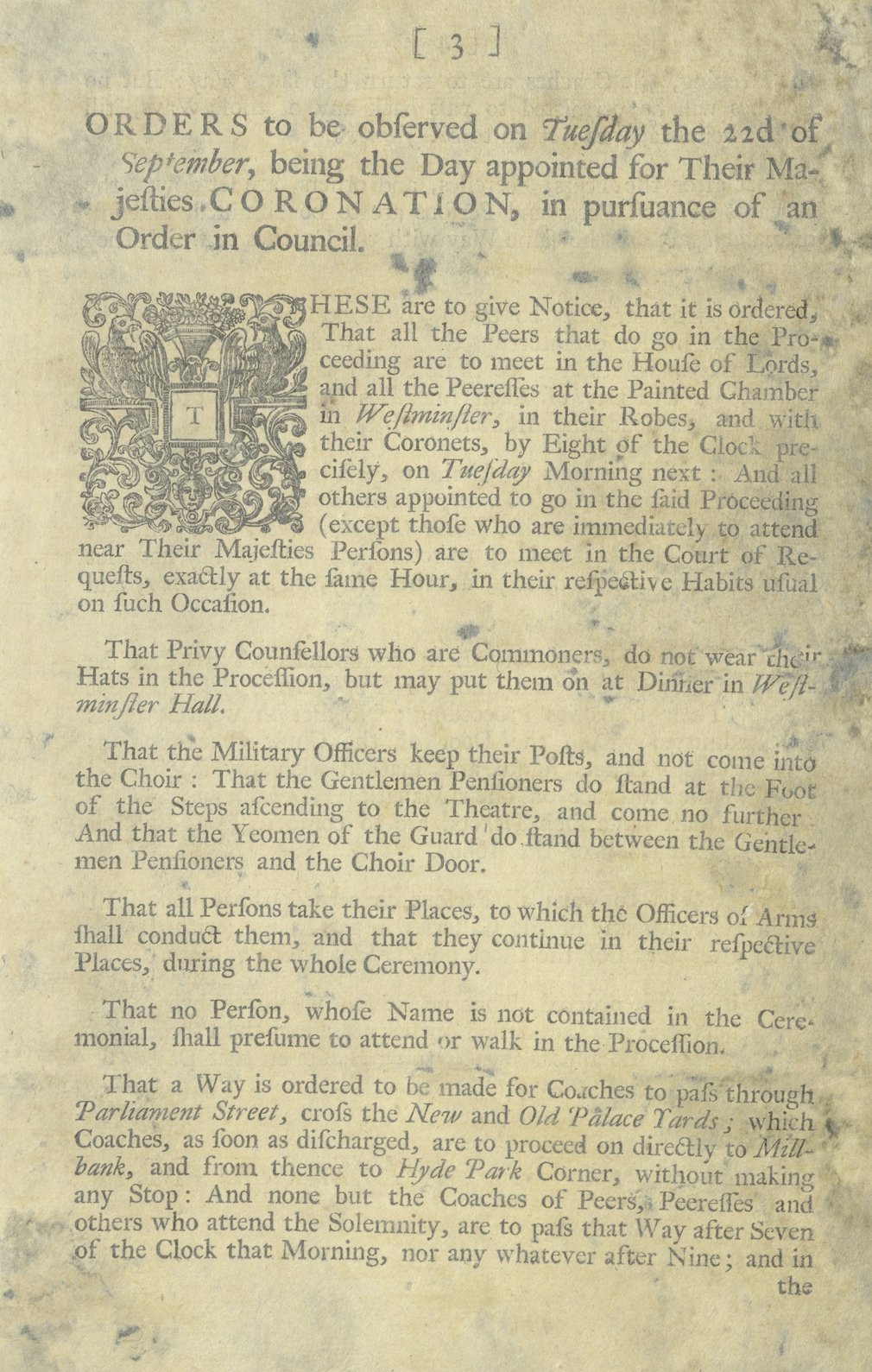

George III’s coronation also features in the collection. Documents give fascinating details of the occasion, including the order of the coronation procession, the regalia of the new king, and instructions for those attending the coronation.

Orders to be observed at the coronation of George III, 1761 GEO/MAIN/15765-66 Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

George III’s private papers feature a significant amount of correspondence with European aristocratic and ruling families, such as the Houses of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Hesse-Cassel, Brunswick and Orange. The letters are often more diplomatic and political in nature than personal however. For example, the King writes to the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel in 1785 that he hopes they ‘will always work together to maintain the German Constitution’, and he professes himself ‘a true friend of the House of Orange’ to the Prince of Orange in 1787. George III also writes a fascinating letter to his sister, Princess Caroline Matilda, on her marriage to King Christian VII of Denmark, urging her to ‘avoid the least appearance of having that weight with him, that [he hopes] she will in reality obtain’, and advising her on how to treat several members of his household.

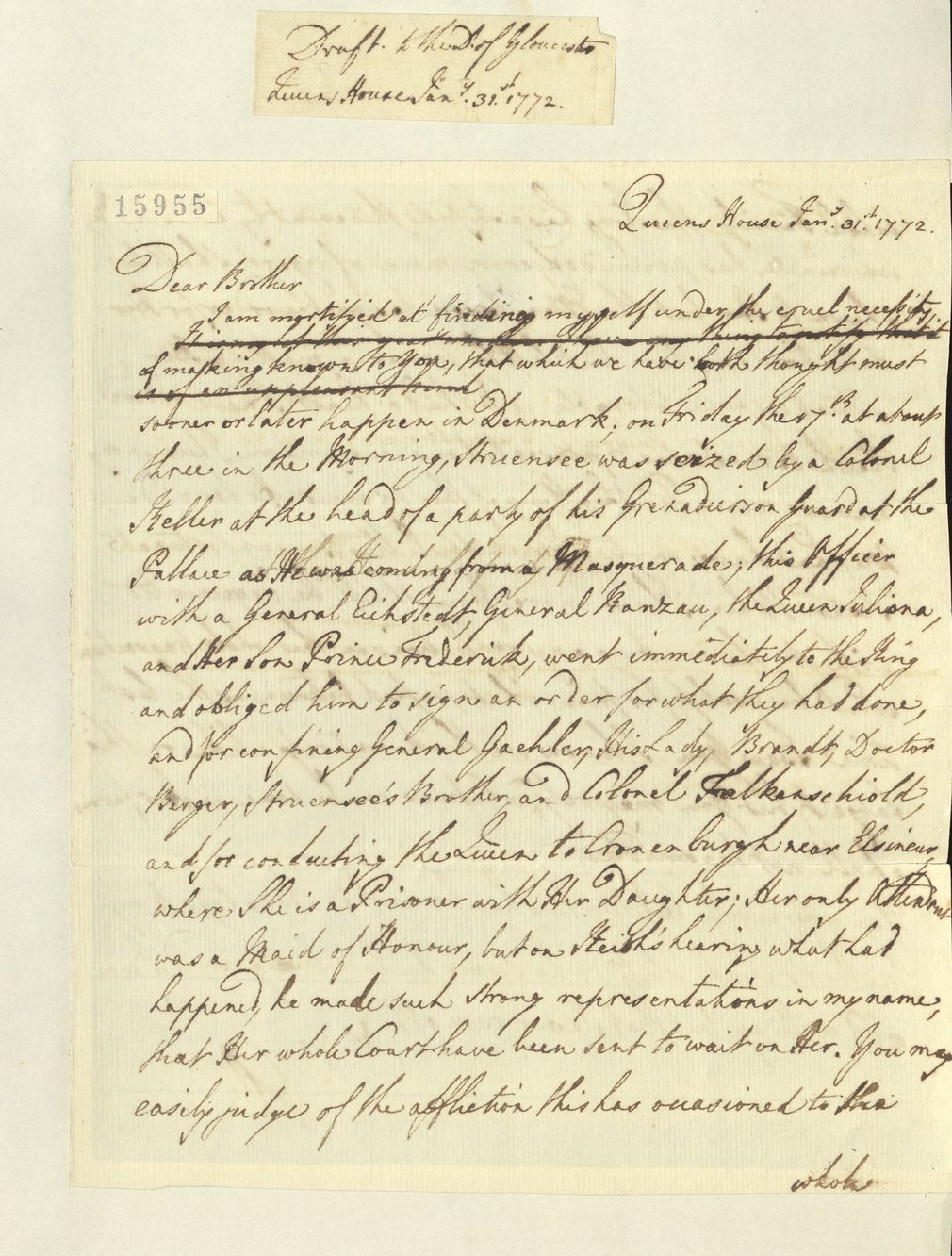

In time, Caroline Matilda’s personal difficulties and indiscretions become an issue that George III attempts to manage. After Christian VII’s de facto regent, Struensee, was arrested on leaving a masquerade, Queen Caroline was removed and imprisoned near Elsinor (described in GEO/MAIN/15955). George III not only supports and appears to believe her innocence (she had been accused of having been Struensee’s lover), but he also arranges for her to establish a court and offers her protection to the point where he jeopardises peace with Denmark.

The collection also sheds light on George III’s Royal Marriages Act of 1772, the creation of which was encouraged by his mother, Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales; on her deathbed, she sought to persuade the King to “apply to Parliament for a prevention to clandestine marriages” in the Royal Family. The creation of the act was prompted by his brother, the Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn, and his marriage to Mrs. Horton in 1771. George III voices his opinion on the matter in his correspondence (see GEO/MAIN/15934 for example) and despite complaining to the Duke of Gloucester about their brother’s marriage and poor behaviour, later finds himself making provision for the child of his own son, Prince Augustus (later Duke of Sussex), from his prohibited marriage to Lady Augusta Murray in 1796.

The private papers also reveal George III’s attitude towards his children and their education. In parallel to his government at the time, the correspondence concerning his children’s education sees him struggle to fill certain posts as various members of the Household resign. He has particular issues with finding tutors for George, Prince of Wales and Prince Frederick, with Lord Holderness accusing the former of being duplicitous and lazy. The letters reveal discussions as to what should be covered in the Princes’ education, with evidence of a particular emphasis on French and German, as well as religion.

The entry of the Princes into the wider world also feature in the papers through reports from the men entrusted with their care and education. Admiral Digby reports on Prince William’s training in the Navy, while Colonel Grenville reports on Prince Frederick’s time in Germany. Criticism comes alongside the praise; George III accuses Prince William of being too fond of horses, and the Prince of Wales of drinking and eating to excess, alongside other examples of poor behaviour. He also takes a personal approach to the education of his sons; the King offers them personal advice in several letters and encourages a sense of responsibility and a trust in religion, or, in the Prince of Wales’ case, criticises his ‘dissipation and extravagance’.

George III’s management of the Prince of Wales throughout his childhood and early adulthood is one of the main themes of this collection. A copy book consisting of 42 letters debates how (i.e by whom), his huge debt should be paid and whether his allowance should be increased, as well as detailing how the Prince of Wales created such a huge debt. Besides his financial concerns, George III considers himself responsible for the Prince’s private life. He offers advice to both the Prince and Princess of Wales as to how they can save their marriage (or at least maintain the appearances of having a functioning relationship to the general public), as well as suggesting that he should be the guardian of Princess Charlotte of Wales.

George III’s Will

This series of documents dates from the period 1820 to 1866, and relates to both George III’s Hanoverian and English wills, detailing the future of his various estates and properties and their contents. The collection also includes correspondence and various notes from his executors concerning the opening of the box containing the will (which is still held by the Royal Archives).

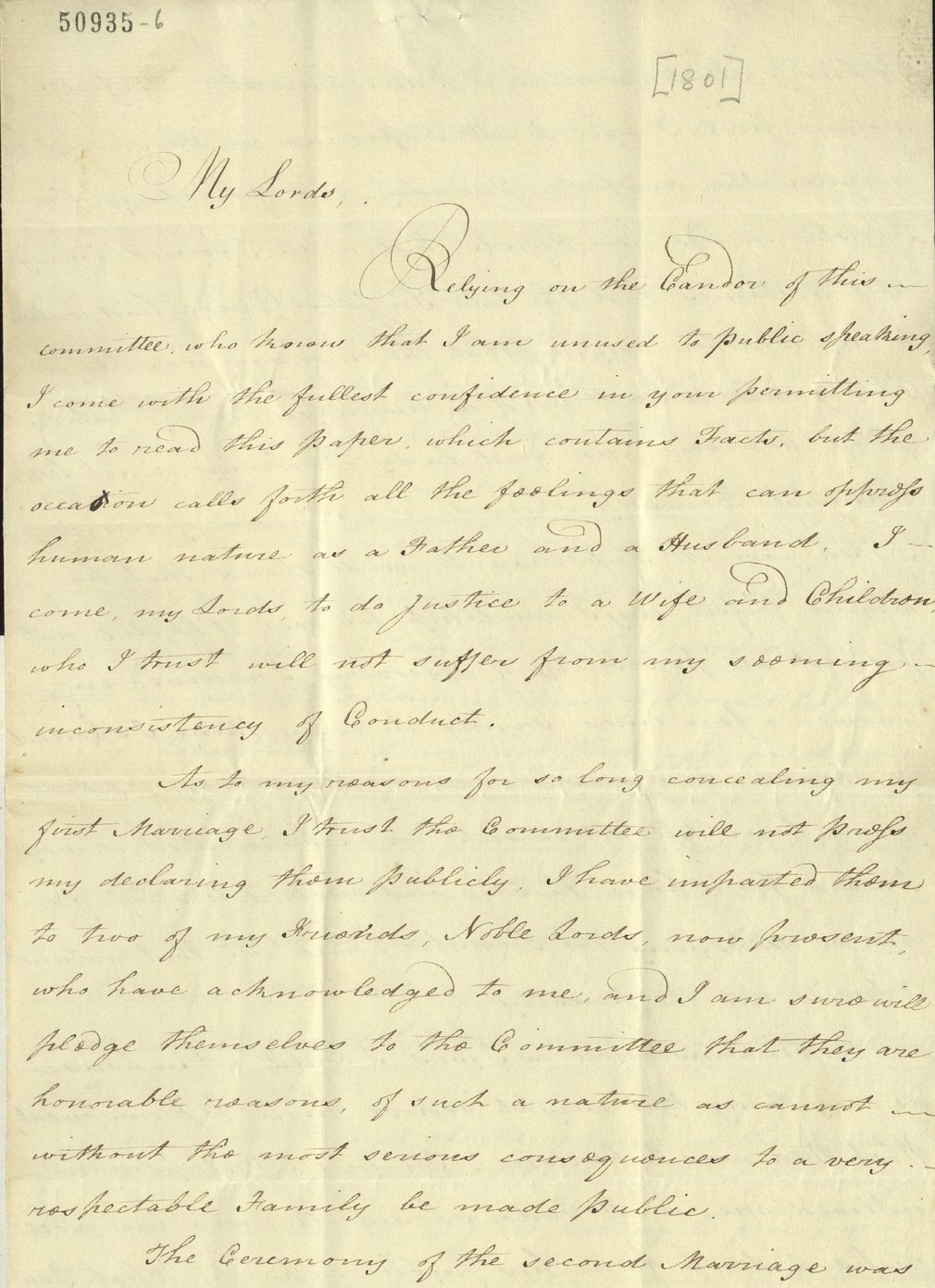

Correspondence concerning the Berkeley Peerage

This collection of correspondence ranges from 1800 to 1822 and covers the case of the proving of the first marriage of the 5th Earl of Berkeley and Mary Cole, also called Tudor. The papers record the case from various perspectives, including a speech from the Earl to the House of Lords, in which he hopes “to do justice to a Wife and Children who [he trusts] will not suffer from my seeming inconsistency of Conduct”, and from his wife, who petitions to have their eldest son recognised as heir long after the earl’s death in 1810. The Prince Regent was one of their most important witnesses, having given a statement that he had been told about their marriage by Lord Berkeley.

Encouraging the Prince Regent to give public support to their cause was another matter, resulting in Lady Berkeley threatening to publish his correspondence concerning the case as well as “publick letters never intended to meet the publick eye-Letters which I much fear will be most unpleasant to the Prince Regent, the Lord Chancellor and more particularly the Duke of Cumberland-It will be Brother against Brother” (GEO/MAIN/50983-50986). The notion of the Prince Regent acting as witness also sparked an interesting debate as to whether or not he should be permitted to give evidence. The document concludes that he should be allowed, citing George III’s appearance in the cases of Abiyne and Clifton and Lea and Lea (GEO/MAIN/51021-51026). The papers do not follow the case through to its conclusion, although we know the Berkeley’s did not win.