George III, when Prince of Wales c.1760-5, RCIN 409153 ©

Although very little of George III’s personal papers survive within the Georgian Papers, we can get an insight to his interests, reading, and thinking through his essays (GEO/ADD/32) and additional papers of a miscellaneous nature (GEO/ADD/2).

Loosely referred to as George III’s essays, these documents were believed to have been created by the schoolboy George when Prince of Wales. However, on closer inspection, the records present a much more interesting – and much more complex – puzzle. While some of these papers do appear to be George’s original creations, many of the so-called ‘essays’ are actually his notes on the work of other writers, most notably the ‘America is lost!’ essay which is drawn from Arthur Young’s Annals of Agriculture. This document is unlikely to have been written much before the publication of Annals in 1784 when George III was in his mid-40s rather than in the first flush of youth.

The precise date of creation for many of the ‘essays’ is unclear. While some of the papers, like that on America mentioned above, is clearly written in a more confident adult hand, it’s notoriously tricky to try to identify the age of the creator or the chronology of the documents based on handwriting alone – which can vary depending on mood, time available, (ill)-health, and age. We can see examples of George III’s handwriting through time in the collection of miscellaneous papers seemingly acquired after the main deposit of records from Apsley House. Many of these papers were purchased by the Royal Archives and so the nature of the documents ranges from personal, such as the letter to the Bishop of Worcester on 6 May 1783 following the death of his son Octavius, to records created in George III’s capacity as head of state, such as his letters to Charles Philip Yorke, Secretary-at-War and later Secretary of State for Home Affairs. The deterioration in George’s eyesight – if not his health – can be clearly seen in two of his signatures (GEO/ADD/2/57 and GEO/ADD/2/56) which are believed to date from 1809 and 1810 respectively – and which have degenerated from a clear, confident hand to an infirm sprawl.

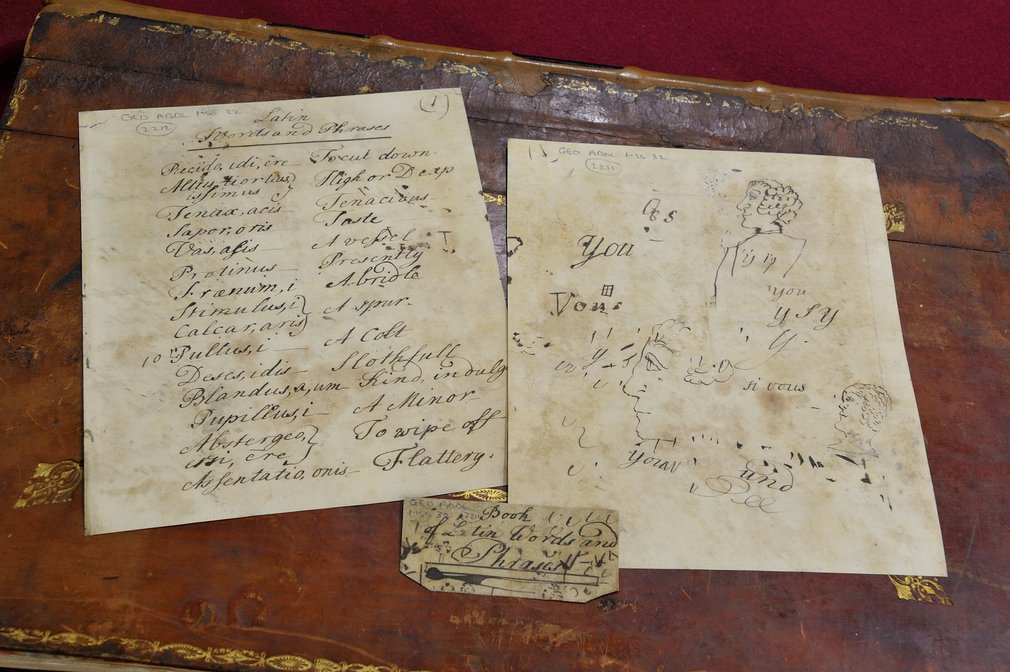

Pages from George III’s essay collection Royal Archives/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Some of the ‘essays’ are obviously written in a more juvenile hand, such as the maths problems. But is this hand that of the young George rather than one of his brothers or indeed one of his sons? Given the quirks of the Georgian Papers, this is something that we can’t take for granted. However, some records we can be sure were written by George and indeed while he was under the tutelage of John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute. In this draft essay on government, we see a sudden change part way through the essay (at folio 1027) from George’s hand to that of Lord Bute and then returning the following page to George’s writing. The influence of Bute on the Prince of Wales, and later the young King, was widely criticised at the time and has been debated and discussed ever since. It is interesting, therefore, that seemingly very few of these ‘essays’ show the hand – physically, at least – of Lord Bute. While there remains much about the ‘essays’ that is yet to be resolved, they remain tangible proof of George III’s lifelong love of learning.